Why do cancer immunotherapies work so extraordinarily well in a minority of patients, but fail in so many others? By analyzing the role of neutrophils, immune cells whose presence usually signals treatment failure, scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), from Harvard Medical School, and from Ludwig Cancer Center have discovered that there is not just one type of neutrophil, but several. Depending on certain markers on their surface, these cells can either promote the growth of tumors, or fight them and ensure the success of a treatment. By boosting the appropriate factors, neutrophils could become great agents of anti-tumor immunity and reinforce the effects of current immunotherapies. These results have been published in the journal Cell.

Immunotherapy involves activating immune cells —mainly T cells—to recognize and destroy cancer cells. While this treatment is very efficient for some patients, and sometimes even exceeds expectations, it is unfortunately not the case in most cases. “The reasons for these failures remain largely unknown,” says Mikaël Pittet, full professor at the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine, holder of the ISREC chair in immuno-oncology, director of the Centre for Translational Research in Onco-Hematology and member of the Ludwig Cancer Center, who directed this work. “This is why deciphering the immune components involved is key to develop more advanced treatments and make immunotherapies a real therapeutic revolution.”

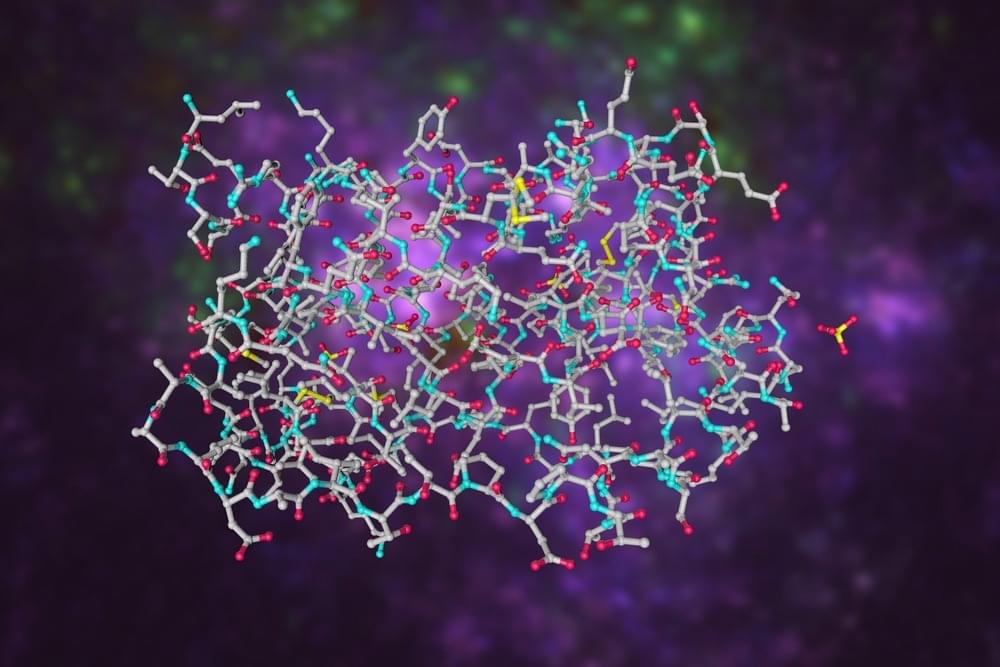

Neutrophils are the most abundant immune cells in the blood and are very useful in infections or injuries by being quickly mobilized to the affected area and releasing antimicrobial factors. In the context of cancer, however, their presence is generally bad news as they promote vascularization and tumor progression.