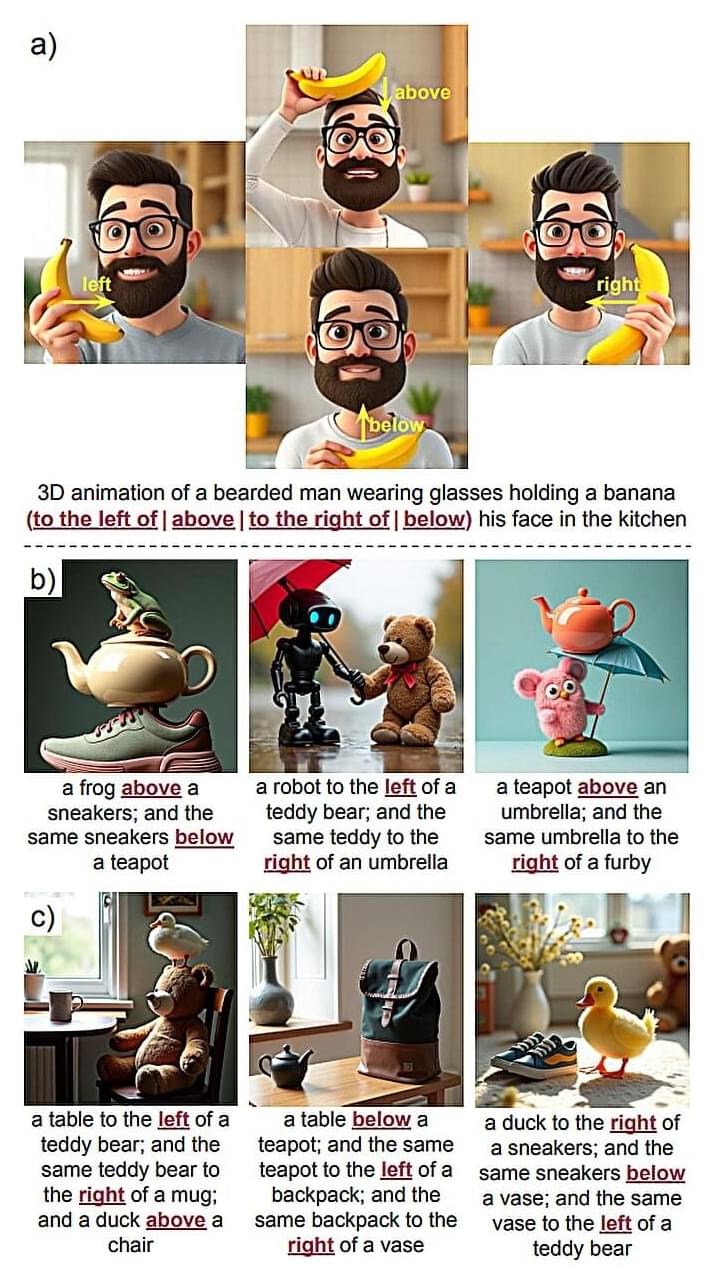

Researchers from the Department of Computer Science at Bar-Ilan University and from NVIDIA’s AI research center in Israel have developed a new method that significantly improves how artificial intelligence models understand spatial instructions when generating images—without retraining or modifying the models themselves. Image-generation systems often struggle with simple prompts such as “a cat under the table” or “a chair to the right of the table,” frequently placing objects incorrectly or ignoring spatial relationships altogether. The Bar-Ilan research team has introduced a creative solution that allows AI models to follow such instructions more accurately in real time.

The new method, called Learn-to-Steer, works by analyzing the internal attention patterns of an image-generation model, effectively offering insight into how the model organizes objects in space. A lightweight classifier then subtly guides the model’s internal processes during image creation, helping it place objects more precisely according to user instructions. The approach can be applied to any existing trained model, eliminating the need for costly retraining.

The results show substantial performance gains. In the Stable Diffusion SD2.1 model, accuracy in understanding spatial relationships increased from 7% to 54%. In the Flux.1 model, success rates improved from 20% to 61%, with no negative impact on the models’ overall capabilities.