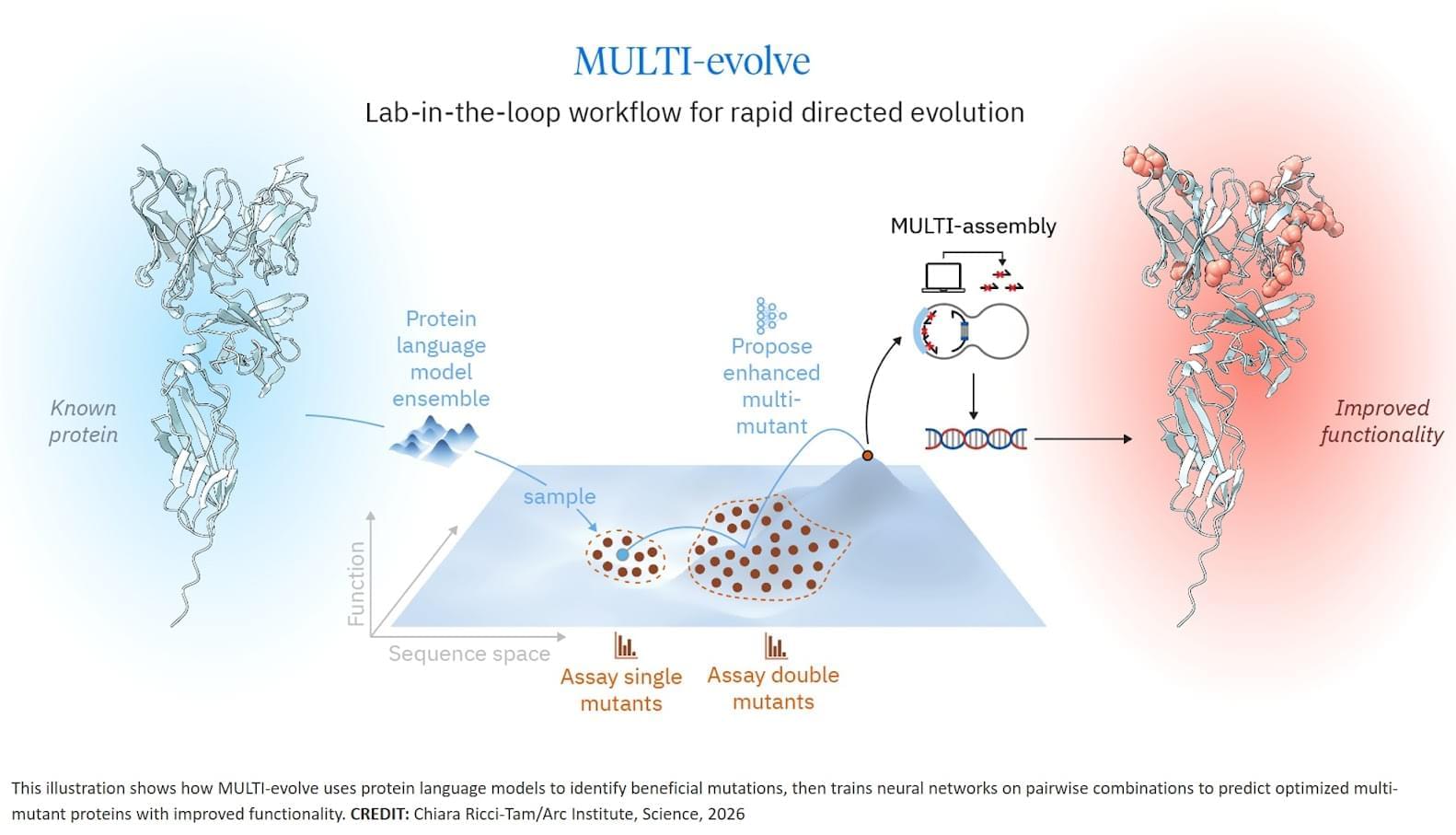

The researchers developed MULTI-evolve, a framework for efficient protein evolution that applies machine learning models trained on datasets of ~200 variants focused specifically on pairs of function-enhancing mutations.

Published in Science, this work represents the first lab-in-the-loop framework for biological design, where computational prediction and experimental design are tightly integrated from the outset, reflecting our broader investment in AI-guided research.

Our insight was to focus on quality over quantity. First identify ~15–20 function-enhancing mutations (using protein language models or experimental screens), then systematically test all pairwise combinations of those beneficial mutations. This generates ~100–200 measurements, and every one is informative for learning beneficial epistatic interactions.

We validated this computationally using 12 existing protein datasets from published studies. Training neural networks on only the single and double mutants, we found models could accurately predict complex multi-mutants (variants with 3–12 mutations) across all 12 diverse protein families. This result held even when we reduced training data to just 10% of what was available.

Training on double mutants works because they reveal epistasis. A double mutant might perform better than the sum of its parts (synergy), worse than expected (antagonism), or exactly as predicted (additivity). These pairwise interaction patterns teach models the rules for how mutations combine, enabling extrapolation to predict which 5-, 6-, or 7-mutation combinations will work synergistically.

We then applied MULTI-evolve to three new proteins: APEX (up to 256-fold improvement over wild-type, 4.8-fold beyond already-optimized APEX2), dCasRx for trans-splicing (up to 9.8-fold improvement), and an anti-CD122 antibody (2.7-fold binding improvement to 1.0 nM, 6.5-fold expression increase). For dCasRx, we started with a deep mutational scan of 11,000 variants, extracted only the function-enhancing mutations, and tested their pairwise combinations—demonstrating the value of strategic data curation for efficient engineering.

Each required experimentally testing only ~100–200 variants in a single round to train models that accurately predicted complex multi-mutants, compressing what traditionally takes 5–10 iterative cycles over many months into weeks. Science Mission sciencenewshighlights.