Recent technological advances have opened new exciting possibilities for the development of smart prosthetics, such as artificial limbs, joints or organs that can replace injured, damaged or amputated body parts. These same advances are also enabling the development of other systems that connect the brain with machines, to record the activity of neurons or allow humans to operate machines in entirely new ways.

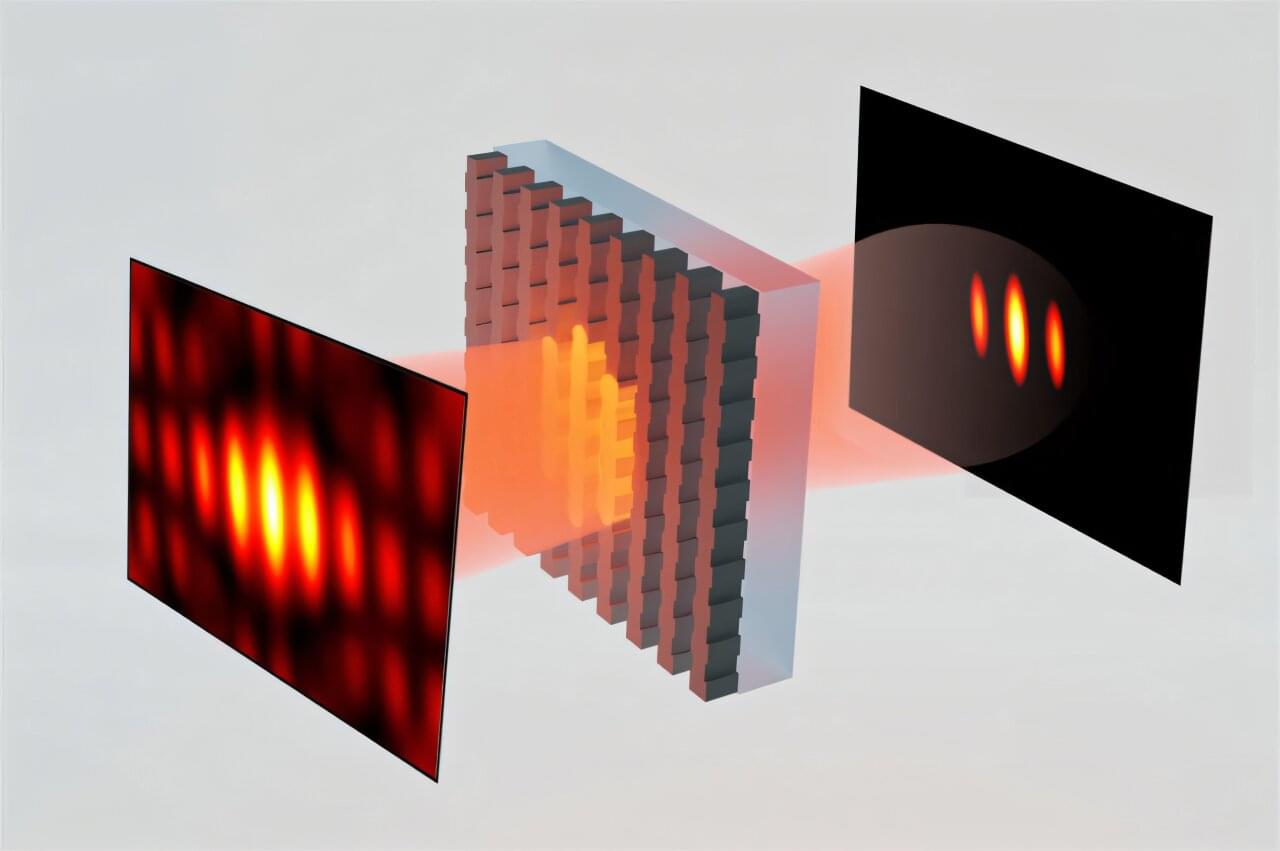

Researchers at the Chinese Institute for Brain Research, the National Center for Nanoscience and Technology in Beijing and other institutes recently developed a new flexible and implantable sensor that can record the activity of neurons in the brain of non-human primates. The sensing device, introduced in a paper published in Nature Electronics, is inspired by kirigami, an artistic discipline that entails the creation of intricate structures by folding and cutting paper in specific ways.

“The development of brain–computer interfaces requires implantable microelectrode arrays that can interface with numerous neurons across large spatial and temporal scales,” wrote Runjiu Fang, Huihui Tian and their colleagues in their paper.