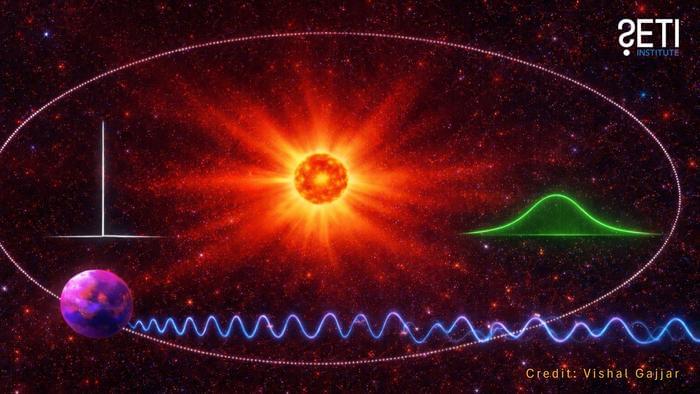

Dr. Vishal Gajjar: “If a signal gets broadened by its own star’s environment, it can slip below our detection thresholds, even if it’s there, potentially helping explain some of the radio silence we’ve seen in technosignature searches.”

What steps can be taken to identify why we haven’t received radio signals from an extraterrestrial intelligence, also called technosignatures? This is what a recent study published in The Astrophysical Journal hopes to address as a team of scientists investigated potential explanations regarding why humanity continues hearing silence from technosignatures. This study has the potential to help scientists and the public better understand the shortcomings and enhancements that can be made in the search for intelligent life beyond Earth.

For the study, the researchers used a series of computer models to simulate how radio signals leaving extrasolar star systems could be influenced by a myriad of factors, specifically space weather coming from the host star. This study comes as SETI and other researchers worldwide continue to come up empty regarding identifying technosignatures. The goal of the study was to ascertain potential reasons while putting constraints on both how and where to search for technosignatures.

In the end, the researchers ascertained that space weather plays a role in altering the outgoing radio signals by dispersing them, as opposed to the radio signals maintaining a fixed beam. The team ascertained that M-dwarf stars, which constitute approximately 75 percent of the stars in the Milky Way Galaxy while being smaller and cooler than our Sun, are prime targets for searching for technosignatures. This is due to their space weather, which is far more active than stars like our Sun, dispersing the radio signals.