Fabricating efficient photocatalysts that can be used in solar-to-fuel conversion and to enhance the photochemical reaction rate is essential to the current energy crisis and climate changes due to the excessive usage of nonrenewable fossil fuels.

Imagine being an explorer, cracking open a 10,000-year-old tomb, uncovering a priceless ancient artifact – and getting rickrolled. Our deep descendants might just get the pleasure, thanks to a Global Music Vault due to be built in Norway, featuring Microsoft’s Project Silica, a tough new data storage medium that’s never gonna give you up.

There’s a common saying that once something is on the internet, it’s there forever, and even if you delete it, it will persist in some server somewhere. But that’s demonstrably untrue – just try to find your cringey old MySpace page. Even the most secure data center is vulnerable to the increasingly common and severe environmental disasters brought on by climate change. Many will lose their data if there’s a long-term power outage, or a large-scale electromagnetic pulse from an attack or, worse still, the Sun. Even in the best-case scenario, physical storage media like Blu-Rays, archival tape, hard drives and even solid state drives will degrade in decades.

To ensure that our history lives on for longer, Microsoft has been experimenting with storing data on glass with what it calls Project Silica. In 2019, the company demonstrated the tech in a partnership with Warner Bros by writing the 1978 movie Superman onto a slide of quartz silica glass and reading it back. The slide, measuring just 75 × 75 mm (3 × 3 in) and 2 mm (0.08 in) thick, could hold as much as 75.6 GB, and remained readable even after being scratched, baked, boiled, microwaved, flooded and demagnetized.

Go to https://ground.news/sabine to get 40% off the Vantage plan and see through sensationalized reporting. Stay fully informed on events around the world with Ground News.

It seems clear that we have given up on trying to stop climate change. It worries me profoundly, not so much because of climate change itself, but because of what it says about our collective ability to make intelligent decisions.

👕T-shirts, mugs, posters and more: ➜ https://sabines-store.dashery.com/

💌 Support me on Donorbox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg.

👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine.

📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/

📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle… Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl… 🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜ / @sabinehossenfelder 📚 Buy my book ➜ https://amzn.to/3HSAWJW #science #climate #environment.

👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl…

🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder.

📚 Buy my book ➜ https://amzn.to/3HSAWJW

#science #climate #environment

Gravity feels reliable—stable and consistent enough to count on. But reality is far stranger than our intuition. In truth, the strength of gravity varies over Earth’s surface. And it is weakest beneath the frozen continent of Antarctica after accounting for Earth’s rotation.

A new study reveals how achingly slow rock movements deep under Earth’s surface over tens of millions of years led to today’s Antarctic gravity hole. The study highlights that the timing of changes in the Antarctic gravity low overlaps with major changes in Antarctica’s climate, and future research could reveal how the shifting gravity might have encouraged the growth of the frozen continent’s climate-defining ice sheets.

“If we can better understand how Earth’s interior shapes gravity and sea levels, we gain insight into factors that may matter for the growth and stability of large ice sheets,” said Alessandro Forte, Ph.D., a professor of geophysics at the University of Florida and co-author of the new study recreating the Antarctic gravity hole’s past.

At the entrance to Starbase in south Texas, a glowing sign now welcomes visitors with the words “Gateway to Mars.” The display sits in front of SpaceX facilities where giant Starship rockets are being assembled with one bold purpose in mind: Elon Musk wants to build a self-sustaining city on Mars.

In recent years he has begun to put numbers on that dream. Musk has repeatedly said that building the first sustainable city on Mars would require around 1,000 Starship rockets and roughly 20 years of launch campaigns, moving up to 100,000 people per favorable Earth-Mars alignment and eventually reaching about one million settlers plus millions of tons of cargo.

It sounds like science fiction with a project plan. Yet the language he uses, “sustainable city,” is very familiar to climate and energy experts here on Earth. So what does sustainability really mean on a frozen, air-thin world and how does that huge effort interact with the environmental crisis on our own planet?

The Technological Singularity is the most overconfident idea in modern futurism: a prediction about the point where prediction breaks. It’s pitched like a destination, argued like a religion, funded like an arms race, and narrated like a movie trailer — yet the closer the conversation gets to specifics, the more it reveals something awkward and human. Almost nobody is actually arguing about “the Singularity.” They’re arguing about which future deserves fear, which future deserves faith, and who gets to steer the curve when it stops looking like a curve and starts looking like a cliff.

The Singularity begins as a definitional hack: a word borrowed from physics to describe a future boundary condition — an “event horizon” where ordinary forecasting fails. I. J. Good — British mathematician and early AI theorist — framed the mechanism as an “intelligence explosion,” where smarter systems build smarter systems and the loop feeds on itself. Vernor Vinge — computer scientist and science-fiction author — popularized the metaphor that, after superhuman intelligence, the world becomes as unreadable to humans as the post-ice age would have been to a trilobite.

In my podcast interviews, the key move is that “Singularity” isn’t one claim — it’s a bundle. Gennady Stolyarov II — transhumanist writer and philosopher — rejects the cartoon version: “It’s not going to be this sharp delineation between humans and AI that leads to this intelligence explosion.” In his framing, it’s less “humans versus machines” than a long, messy braid of tools, augmentation, and institutions catching up to their own inventions.

One of the biggest challenges in climate science and weather forecasting is predicting the effects of turbulence at spatial scales smaller than the resolution of atmospheric and oceanic models. Simplified sets of equations known as closure models can predict the statistics of this “subgrid” turbulence, but existing closure models are prone to dynamic instabilities or fail to account for rare, high-energy events. Now Karan Jakhar at the University of Chicago and his colleagues have applied an artificial-intelligence (AI) tool to data generated by numerical simulations to uncover an improved closure model [1]. The finding, which the researchers subsequently verified with a mathematical derivation, offers insights into the multiscale dynamics of atmospheric and oceanic turbulence. It also illustrates that AI-generated prediction models need not be “black boxes,” but can be transparent and understandable.

The team trained their AI—a so-called equation-discovery tool—on “ground-truth” data that they generated by performing computationally costly, high-resolution numerical simulations of several 2D turbulent flows. The AI selected the smallest number of mathematical functions (from a library of 930 possibilities) that, in combination, could reproduce the statistical properties of the dataset. Previously, researchers have used this approach to reproduce only the spatial structure of small-scale turbulent flows. The tool used by Jakhar and collaborators filtered for functions that correctly represented not only the structure but also energy transfer between spatial scales.

They tested the performance of the resulting closure model by applying it to a computationally practical, low-resolution version of the dataset. The model accurately captured the detailed flow structures and energy transfers that appeared in the high-resolution ground-truth data. It also predicted statistically rare conditions corresponding to extreme-weather events, which have challenged previous models.

A combined experimental and theoretical study reveals the emergence of quantum chaos in a complex system, suggesting that it can be described with a universal theoretical framework.

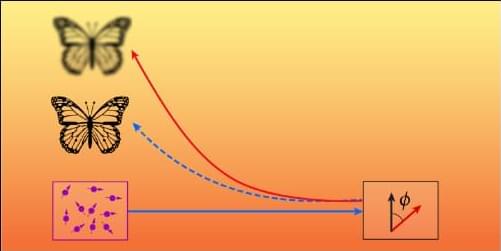

Consider the following thought experiment: Take all the air molecules in a thunderstorm and evolve them backward in time for an hour, effectively rewinding a molecular movie. Then slightly perturb the velocity directions of a few molecules and evolve the system forward again to the current moment. Because such systems are chaotic, microscopic perturbations in the past will lead to dramatically different futures. This “butterfly effect” also occurs in quantum systems. To observe it, researchers measure a mathematical entity called the out-of-time-ordered correlator (OTOC). Loosely speaking, the OTOC measures how quickly a system “forgets” its initial state. Unfortunately, the OTOC is notoriously difficult to measure because it typically requires experimental protocols that implement an effective many-body time reversal.

The sun is the basis for photosynthesis, but not all plants thrive in strong sunlight. Strong sunlight constrains plant diversity and plant biomass in the world’s grasslands, a new study shows. Temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric nitrogen deposition have less impact on plant diversity. These results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by a research team led by Marie Spohn from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

The steppes of North America, the Serengeti savanna, the Svalbard tundra and natural pastures in the Alps are examples of habitats that are described as grasslands, with the common feature that there are no trees and the vegetation is dominated by grasses and other herbaceous plants. The diversity of plant species in these grasslands varies considerably, but the question of what controls plant diversity has challenged researchers for decades.

Last year, in a study on grasslands, Spohn from SLU and colleagues found that soil properties and climate factors, such as temperature, did not explain variations in plant diversity. “This finding surprised me,” says Spohn. “And that’s when I started wondering about the importance of sunlight for plant diversity in grasslands and decided to start a new project that would explore this relationship.”