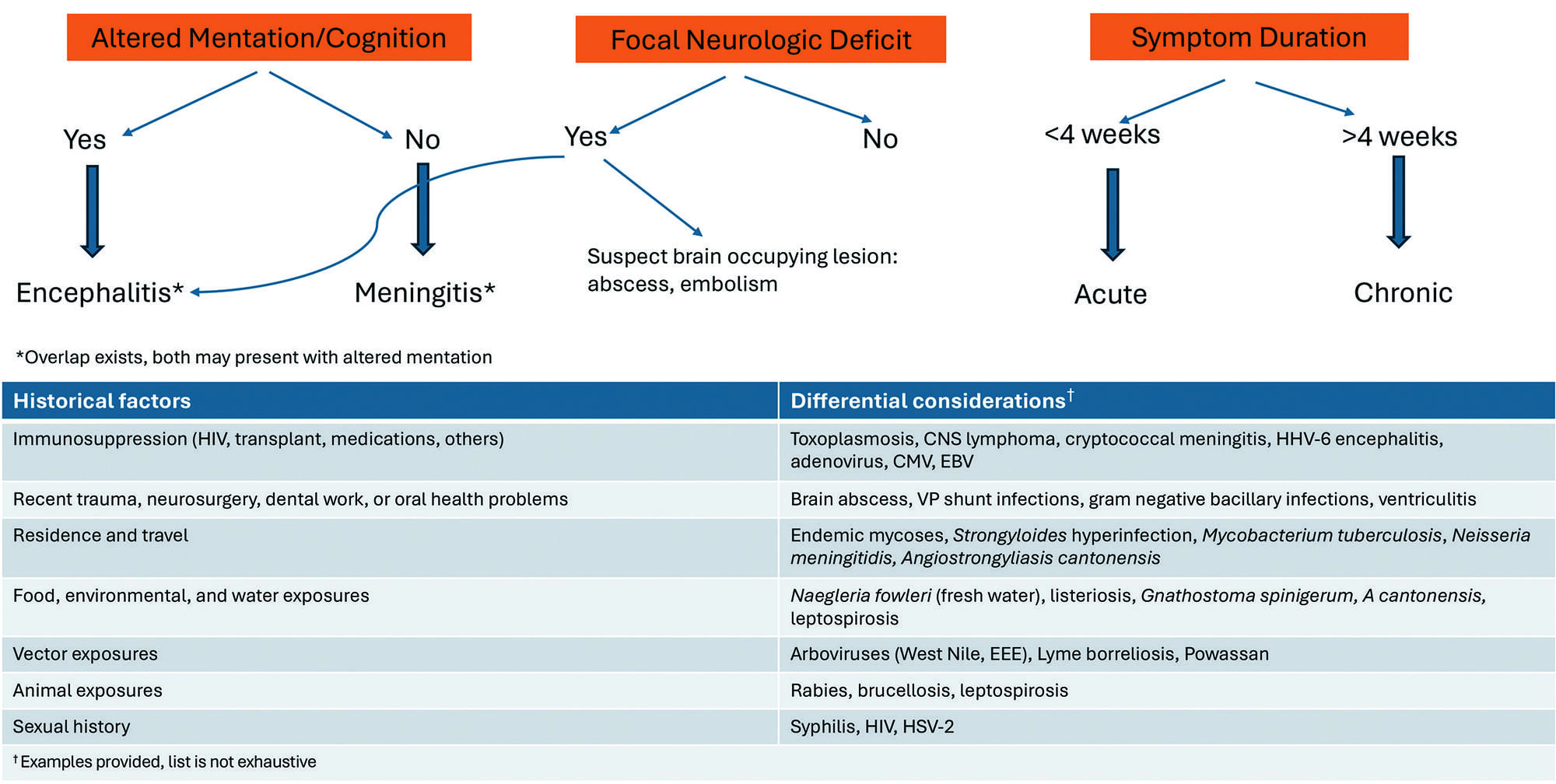

Headache accompanied by fever can indicate a wide range of disorders, making prompt and comprehensive evaluation crucial to identify the underlying cause.

Microscopy has long been essential to biomedical research, enabling detailed analyses of complex samples. Fourier ptychographic microscopy (FPM), a computational imaging technique, provides high-resolution, wide-field images without requiring extensive hardware modifications. However, current FPM algorithms struggle with samples exhibiting depth variations, such as tilted or 3-dimensional (3D) objects. The limited depth of field (DoF) leads to images with only focal-plane areas in sharp focus, while regions outside appear blurred. To address this limitation, we propose an all-in-focus FPM algorithm using physics-informed 3D neural representations to reconstruct sharp, wide-field images of 3D objects under limited DoF. Unlike previous methods, our approach samples the full depth range to create a 3D feature volume that incorporates spatial and depth information.

Three centuries after Newton described the universe through fixed laws and deterministic equations, science may be entering an entirely new phase.

According to biochemist and complex systems theorist Stuart Kauffman and computer scientist Andrea Roli, the biosphere is not a predictable, clockwork system. Instead, it is a self-organising, ever-evolving web of life that cannot be fully captured by mathematical models.

Organisms reshape their environments in ways that are fundamentally unpredictable. These processes, Kauffman and Roli argue, take place in what they call a “Domain of No Laws.”

This challenges the very foundation of scientific thought. Reality, they suggest, may not be governed by universal laws at all—and it is biology, not physics, that could hold the answers.

Tap here to read more.

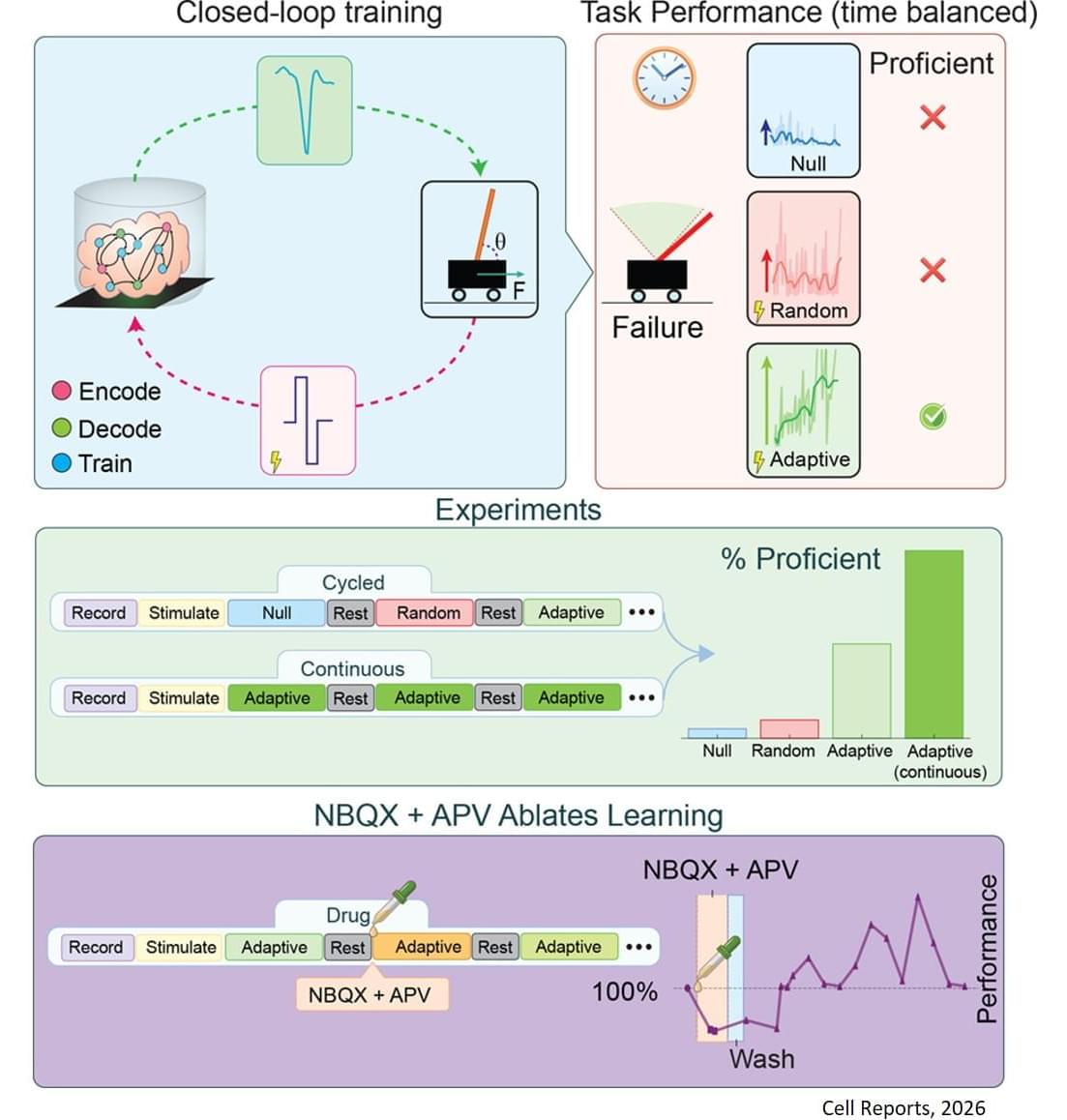

This research is the first rigorous academic demonstration of goal-directed learning in lab-grown brain organoids, and lays the foundation for adaptive organoid computation—exploring the capacity of lab-grown brain organoids to learn and solve tasks.

Using organoids derived from mouse stem cells and an electrophysiology system developed by industry partners Maxwell Biosciences, the researchers use electrical simulation to send and receive information to and from neurons. By using stronger or weaker signals, they communicate to the organoid the angle of the pole, which exists in a virtual environment, as it falls in one direction or the other. As this happens, the researchers observe as the organoid sends back signals of how to apply force to balance the pole, and they apply this force to the virtual pole.

For their pole-balancing experiments, the researchers observe as the organoid controls the pole until it drops, which is called an episode. Then, the pole is reset and a new episode begins. In essence, the organoid plays a video game in which the goal is to balance the pole upright for as long as possible.

The researchers observe the organoid’s progress in five-episode increments. If the organoid keeps the pole upright for longer on average in the past five episodes as compared to the past 20, it receives no training signal since it has been improving. If it does not improve the average time it keeps the pole upright, it receives a training signal.

Training feedback is not given to the organoid while it is balancing the pole—only at the end of an episode. An AI algorithm called reinforcement learning is used to select which neurons within the organoid get the training signal.

The results of this study prove that the reinforcement learning algorithm can guide the brain organoids toward improved performance at the cart-pole task—meaning organoids can learn to balance the pole for longer periods of time.

The researchers adopted a rigorous framework for success to make sure they were observing true improvement, and not just random success, including a threshold for the minimum time an organoid needs to balance the pole to “win” the game.

From the article:

“A Rule for Every Curve”

That’s where the new proof comes in. Its authors present a formula that can be applied to any curve in the mathematical universe, whatever its degree. It doesn’t say precisely how many rational points that curve has, but it gives an upper limit on what that number can be.

Previous formulas of this kind either didn’t apply to all curves or depended on the specific equation used to define them. The new formula is something mathematicians have hoped for since Faltings’s proof, a “uniform” statement that applies to all curves without depending on the coefficients in their equations. “This one statement gives us a broad sweep of understanding,” Mazur says.

It depends on only two things. The first is the degree of the polynomial that defines the curve—the higher the degree is, the weaker the statement becomes. The second thing the formula depends on is called the “Jacobian variety,” a special surface that can be constructed from any curve. Jacobian varieties are interesting in their own right, and the formula offers a tantalizing path for studying them as well.”

Since ancient Greece, researchers have tried to isolate special rational points on curves. Now they have the first ever formula that applies uniformly to all curves.

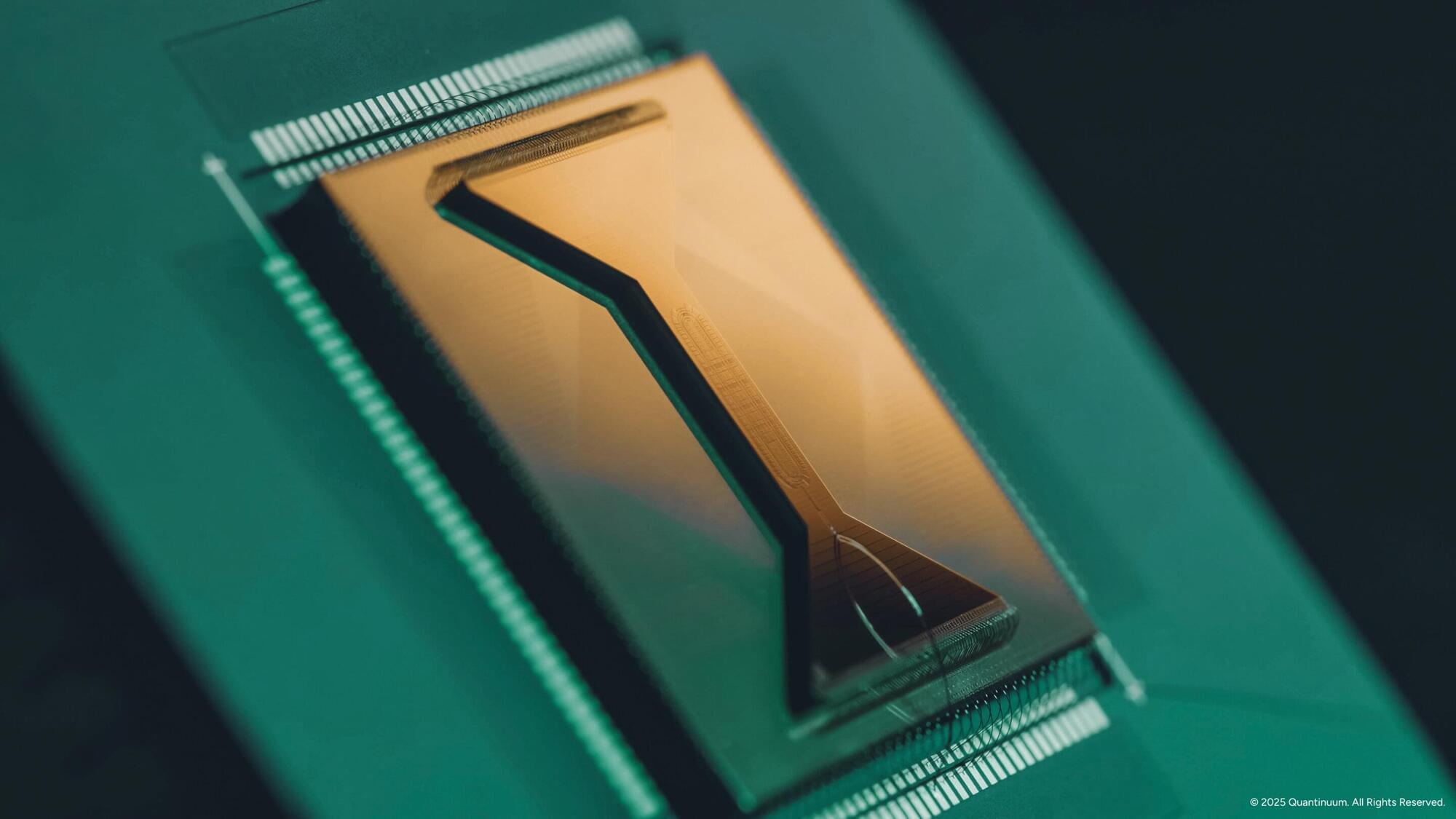

Quantum computers—devices that process information using quantum mechanical effects—have long been expected to outperform classical systems on certain tasks. Over the past few decades, researchers have worked to rigorously demonstrate such advantages, ideally in ways that are provable, verifiable and experimentally realizable.

A team of researchers working at Quantinuum in the United Kingdom and QuSoft in the Netherlands has now developed a quantum algorithm that solves a specific sampling task—known as complement sampling—dramatically more efficiently than any classical algorithm. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, establishes a provable and verifiable quantum advantage in sample complexity: the number of samples required to solve a problem.

“We stumbled upon the core result of this work by chance while working on a different project,” Harry Buhrman, co-author of the paper, told Phys.org. “We had a set of items and two quantum states: one formed from half of the items, the other formed from the remaining half. Even though the two states are fundamentally distinct, we showed that a quantum computer may find it hard to tell which one it is given. Surprisingly, however, we then realized that transforming one state into the other is always easy, because a simple operation can swap between them.”

The collaboration of TU Wien with research groups in China has resulted in a crucial building block for a new kind of quantum computer: The realization of a novel type of quantum logic gate makes it possible to carry out quantum computations on pairs of photons that are each in four different quantum states, or combinations thereof. The advancement is an important milestone for optical quantum computers. The study has now been published in Nature Photonics.

The basic idea of quantum computers is simple: While a classical computer only works with the values “0” and “1,” quantum physics allows for arbitrary combinations of these states. In a certain sense, a quantum bit (“qubit”) can be in the states 0 and 1 simultaneously. This makes it possible to develop algorithms that can solve some problems much faster than a comparable classical computer.

However, such superpositions can in principle involve more than two states. Depending on what degree of freedom one considers, a quantum system such as a photon may not just have two different settings—two different outcomes of a potential measurement—but many. In this case, one refers to the system as a “qudit” rather than a “qubit.”