While 2026 has been an objectively terrible year for humans thus far, it’s turning out—for better or worse—to be a banner year for robots. (Robots that are not Tesla’s Optimus thingamajig, anyway.) And it’s worth thinking about exactly how remarkable it is that the new humanoid robots are able to replicate the smooth, fluid, organic movements of humans and other animals, because the majority of robots do not move like this.

Take, for example, the robot arms used in factories and CNC machines: they glide effortlessly from point to point, moving with both speed and exquisite precision, but no one would ever mistake one of these arms for that of a living being. If anything, the movements are too perfect. This is at least partly due to the way these machines are designed and built: they use the same ideas, components, and principles that have characterised everything from the water wheel to the combustion engine.

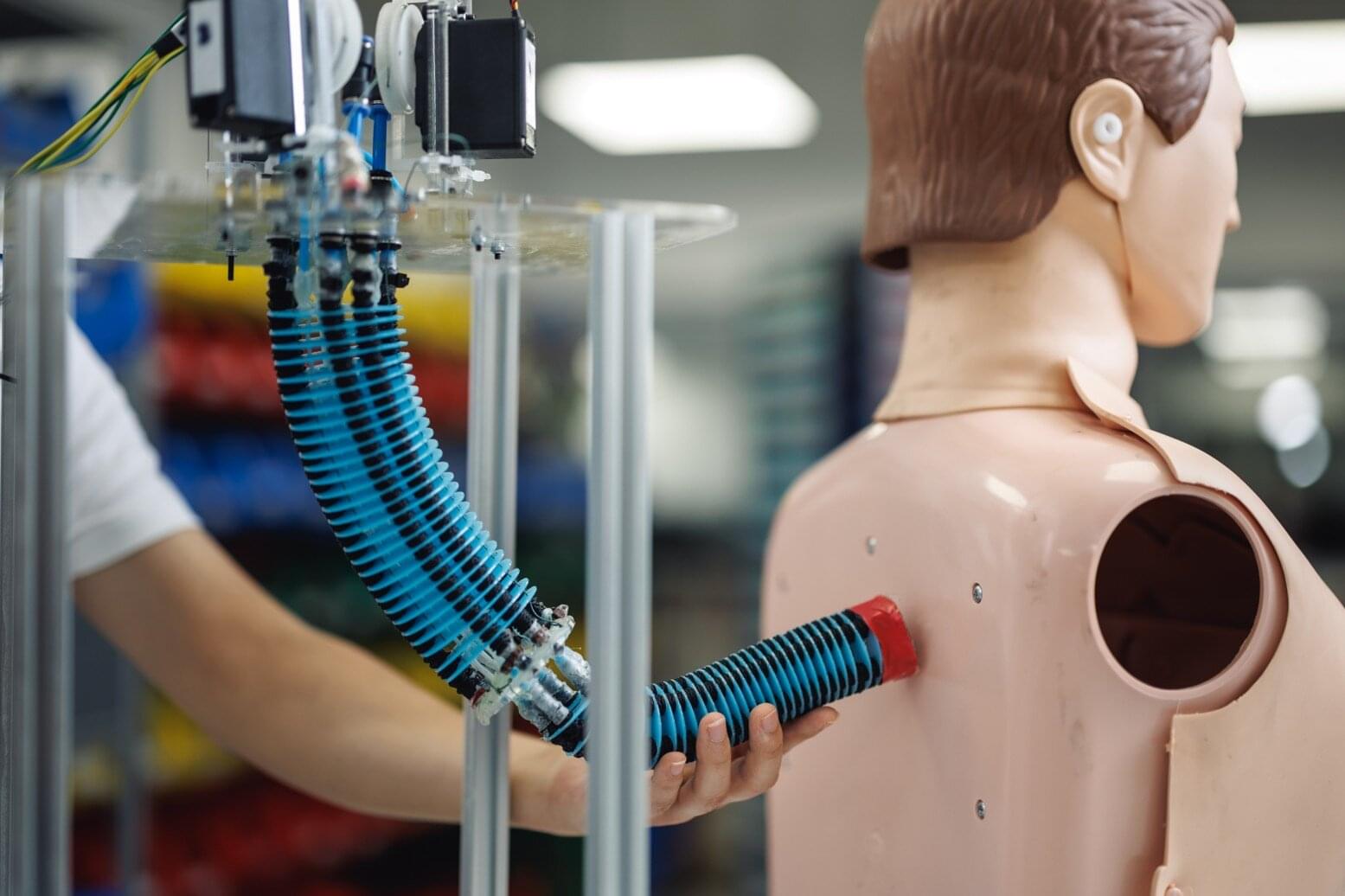

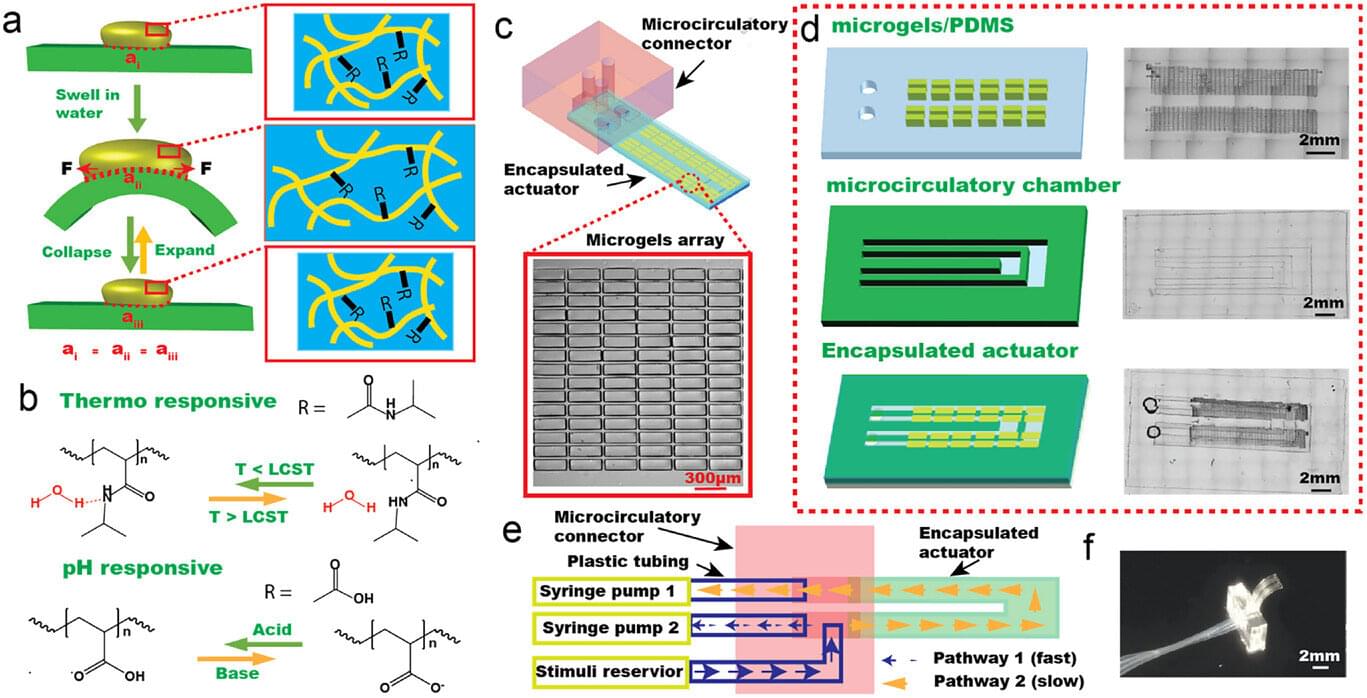

But that’s not how living creatures work. While the overwhelming majority of macroscopic living beings contain some sort of “hard” parts—bones or exoskeletons—our movements are driven by muscles and ligaments that are relatively soft and elastic.