A rare, half-billion-year-old fossil gives us a clue to how a bizarre marine invertebrate can possibly be related to humans. In a study published on July 6 in the journal Nature Communications, Harvard University researchers identified a prehistoric specimen in a collection at the Natural History Museum of Utah as a tunicate, or sea squirt. The preserved invertebrate, which was originally discovered in the rugged, desert-like landscape of the House Range in western Utah, can be used to understand evolution mysteries that go way back to the Cambrian explosion.

“There are essentially no tunicate fossils in the entire fossil record. They’ve got a 520-to 540-million year-long gap,” says Karma Nanglu, an invertebrate paleontologist at Harvard. “This fossil isthe first soft-tissue tunicate in, we would argue, the entire fossil record.”

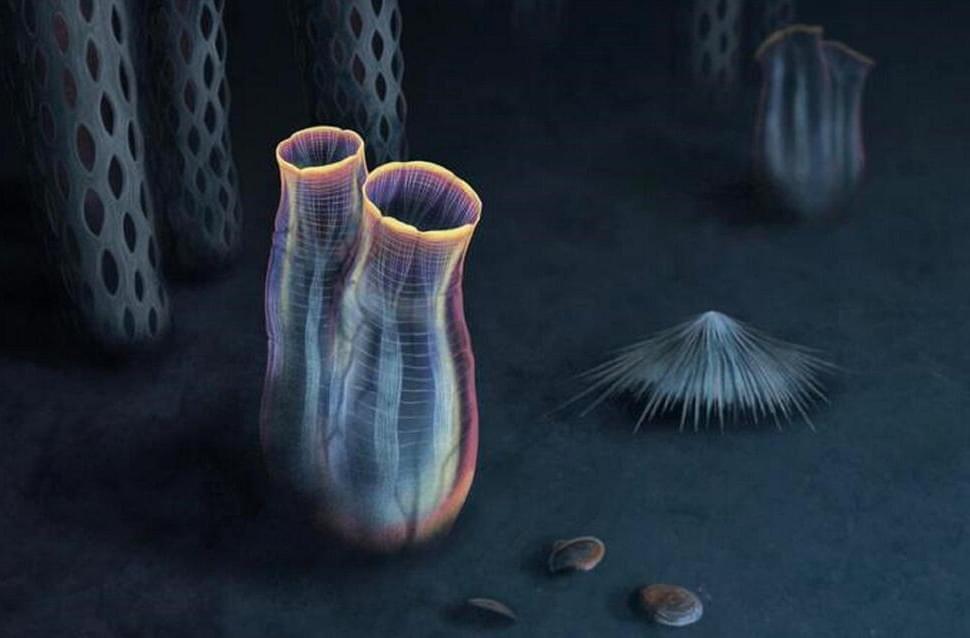

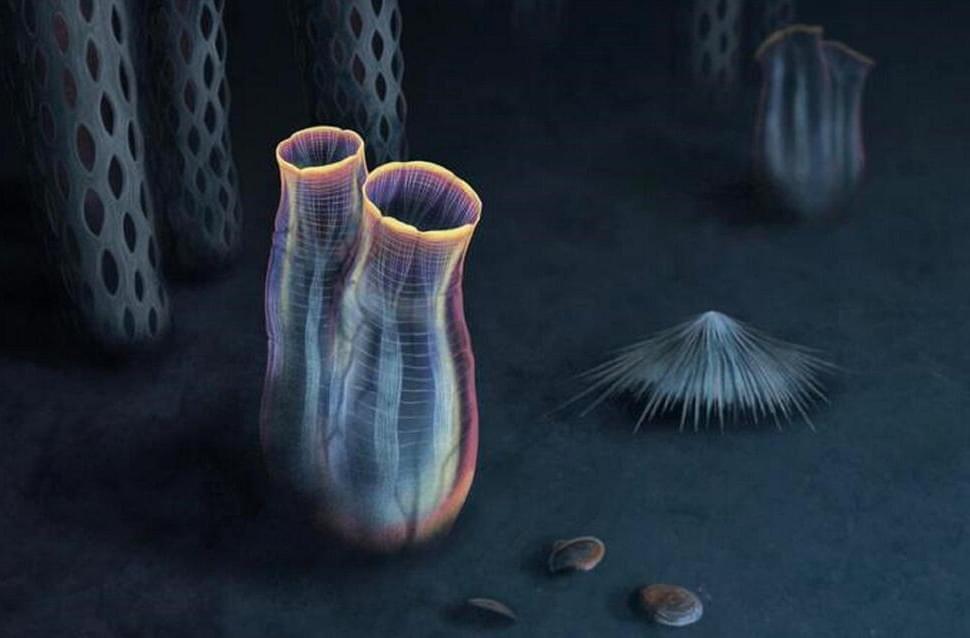

Sea squirts can be seen swaying on the ocean floor with its potato-like body and two chimney-like parts called siphons that are used to feed and expel water. While there are at least 3,000 different species today, the crayon-point-size organisms are generally unknown to people—despite being our invertebrate cousins, says Nanglu. Like humans, they belong to the chordates, which share five essential physical features during development or when fully grown. Most tunicates hatch as swimming, tadpole-like creatures, but eventually attach to the ocean floor and lead a sessile lifestyle.