Aug 19, 2022

Forever Chemicals No More? PFAS Are Destroyed With New Technique

Posted by Genevieve Klien in category: chemistry

The harmful molecules are everywhere, but chemists have made progress in developing a method to break them down.

The harmful molecules are everywhere, but chemists have made progress in developing a method to break them down.

Scientists experimenting with next-generation plastics at Finland’s University of Turku have developed a form of the material with some impressive capabilities, most notably an ability to quickly break down after use. The eco-friendly “supramolecular” plastic is therefore highly recyclable and, with careful tuning of its water content, can be turned into an adhesive or even instantly self-heal when damaged.

The reason conventional plastics persist in the environment for so long is the incredibly strong chemical connections between the monomers within them. These particles link up to form polymers through what are known as covalent bonds, but scientists hope to fashion more environmentally forms of the material based on non-covalent bonds instead.

These weaker connections are better suited to degradation and recycling of the material, but do come at a cost in terms of mechanical performance. We have looked at some interesting examples of these “supramolecular” materials in the form of hybrid polymers for drug delivery, self-assembling plastics and adhesives that work at extreme temperatures.

Chiral polymer made from completely achiral chemicals using only electrons’ angular momentum.

Source:

#neuroscience #neurotwitter #neurology #science #sciencetwitter #medtwitter #Bioinformatics #biochemistry #biotechnology #anatomy #neuroanatomy

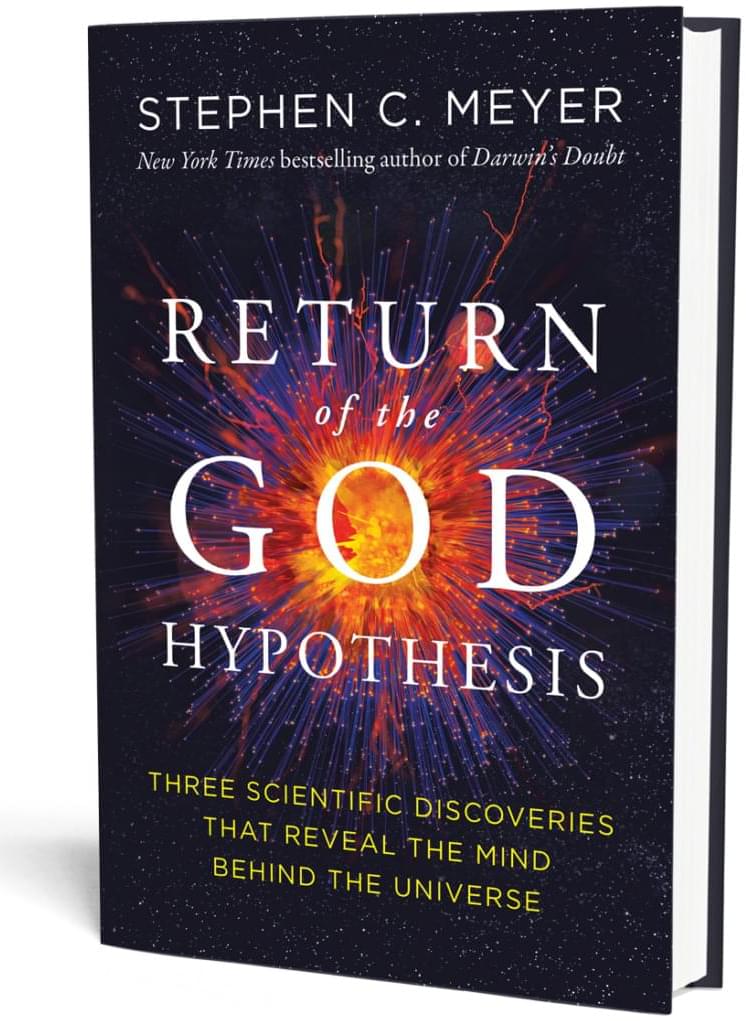

In this second portion of a talk at the Dallas Conference on Science and Faith (2021), philosopher Steve Meyer discusses the ways in which groundbreaking astronomer Fred Hoyle (1915–2001) dealt with the fact that the universe seems fine-tuned for life. Hoyle’s widely cited comment on the subject was “A commonsense interpretation of the facts suggests that a superintellect has monkeyed with physics, as well as chemistry and biology, and that there are no blind forces worth speaking about in nature.” That was an unsettling idea for Hoyle, who was a well-known atheist, and he certainly sought ways around it. How did he fare?

The chip is an artificial neuron, but nothing like previous chips built to mimic the brain’s electrical signals. Rather, it adopts and adapts the brain’s other communication channel: chemicals.

Called neurotransmitters, these chemicals are the brain’s “natural language,” said Dr. Benhui Hu at Nanjing Medical University in China. An artificial neuron using a chemical language could, in theory, easily tap into neural circuits—to pilot a mouse’s leg, for example, or build an entirely new family of brain-controlled prosthetics or neural implants.

A new study led by Hu and Dr. Xiaodong Chen at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, took a lengthy stride towards seamlessly connecting artificial and biological neurons into a semi-living circuit. Powered by dopamine, the setup wasn’t a simple one-way call where one component activated another. Rather, the artificial neuron formed a loop with multiple biological counterparts, pulsing out dopamine while receiving feedback to change its own behavior.

Down the line, the researchers hope to develop an injectable protein solution that forms a gel inside the body. The ability to design hydrogels with specific functions opens up for a range of possible applications. Such a gel could, for example, be used to achieve a controlled release of drugs into the body. In the chemical industry, it could be fused to enzymes, a form of proteins used to speed up various chemical processes.

“In the slightly longer term, I think injectable gels can become very useful in regenerative medicine,” says the study’s first author Tina Arndt, a PhD student in Anna Rising’s research group at Karolinska Institute. “We have a long way to go, but the fact that the protein solution quickly forms a gel at body temperature and that the spider silk has been shown to be well tolerated by the body is promising.”

The ability of spiders to spin incredibly strong fibers from a silk protein solution in fractions of a second has sparked an interest in the underlying molecular mechanisms. The researchers at KI and SLU have been particularly interested in the spiders’ ability to keep proteins soluble so that they do not clump together before the spinning of the spider silk. They have previously developed a method for the production of valuable proteins which mimics the process the spider uses to produce and store its silk proteins.

Certain tasks—such as recognizing patterns and language—are performed highly efficiently by a human brain, requiring only about one ten-thousandth of the energy of a conventional, so-called “von Neumann” computer. One of the reasons lies in the structural differences: In a von Neumann architecture, there is a clear separation between memory and processor, which requires constant moving of large amounts of data. This is time-and energy-consuming—the so-called von Neumann bottleneck. In the brain, the computational operation takes place directly in the data memory and the biological synapses perform the tasks of memory and processor at the same time.

In Forschungszentrum Jülich, scientists have been working for more than 15 years on special data storage devices and components that can have similar properties to the synapses in the human brain. So-called memristive memory devices, also known as memristors, are considered to be extremely fast and energy-saving, and can be miniaturized very well down to the nanometer range. The functioning of memristive cells is based on a very special effect: Their electrical resistance is not constant, but can be changed and reset again by applying an external voltage, theoretically continuously. The change in resistance is controlled by the movement of oxygen ions. If these move out of the semiconducting metal oxide layer, the material becomes more conductive and the electrical resistance drops. This change in resistance can be used to store information.

The processes that can occur in cells are complex and vary depending on the material system. Three researchers from the Jülich Peter Grünberg Institute—Prof. Regina Dittmann, Dr. Stephan Menzel, and Prof. Rainer Waser—have therefore compiled their research results in a detailed review article, “Nanoionic memristive phenomena in metal oxides: the valence change mechanism.” They explain in detail the various physical and chemical effects in memristors and shed light on the influence of these effects on the switching properties of memristive cells and their reliability.

While scientists have hoped that rechargeable zinc-manganese dioxide batteries could be developed into a viable alternative for grid storage applications, engineers at the University of Illinois Chicago and their colleagues identified the reasons these zinc-based fuel systems fail.

The scientists reached this conclusion after leveraging advanced electron microscopy, electrochemical experiments and theoretical calculations to look closer at how the zinc anode works with the manganese cathode in the battery system.

Their findings are reported today in Nature Sustainability.

A new study says that changing guidelines for forever chemicals have made rainwater all around the world unsafe to drink.

Rainwater is an important part of our planet’s ecosystem, and it helps fuel access to drinking water in many places. However, a new study suggests that rainwater is now unsafe to drink. The study says that “forever chemicals” have reached unsafe levels. These forever chemicals are scientifically known as per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and they don’t break down in the environment.

You can find PFAS chemicals in non-stick and stain-repellent properties. As such, they’re found in a lot of household food packages, electronics, and even cosmetics and cookware. However, it seems that these chemicals are now mixing with our rainwater. As a result, it has made rainwater unsafe to drink. And researchers say they can’t tie this issue to just one location. It’s everywhere in the world, even in Antarctica.

Continue reading “New study says rainwater is now unsafe to drink” »