In a study published in Nature, a UCLA-led team of researchers describe how the nanomachine recognizes and kills bacteria, and report that they have imaged it at atomic resolution. The scientists also engineered their own versions of the nanomachine, which enabled them to produce variations that behaved differently from the naturally occurring version.

Their efforts could eventually lead to the development of new types of antibiotics that are capable of homing in on specific species of microbes. Drugs tailored to kill only a certain species or strain of bacteria could offer numerous advantages over conventional antibiotics, including lowering the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance. In addition, the tailored drugs could destroy harmful cells without wiping out beneficial bugs in the gut microbiome, and they could eventually offer the possibilities of being deployed to prevent bacterial infections, to kill pathogens in food and to engineer human microbiomes so that favorable bacteria thrive.

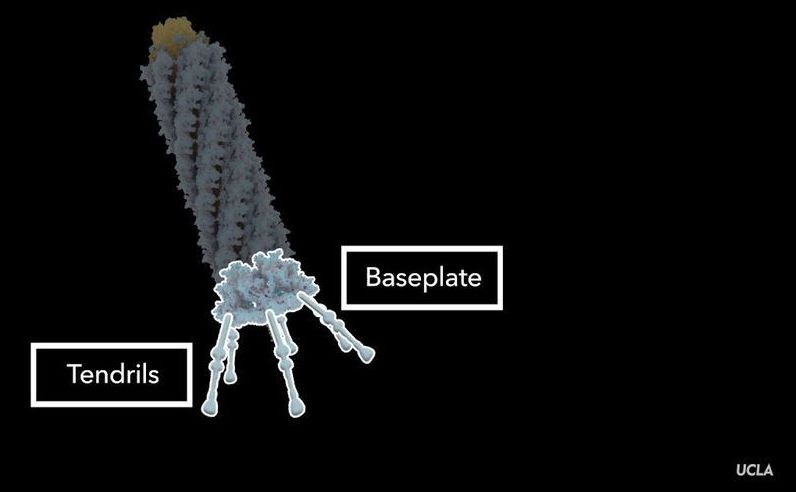

The particle in the study, an R-type pyocin, is a protein complex released by the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a way of sabotaging microbes that compete with it for resources. When a pyocin identifies a rival bacterium, it kills the bacterium by punching a hole in the cell’s membrane. P. aeruginosa, frequently a cause of hospital-acquired illness, is found in soil, in water and on fresh produce. The germ is commonly studied and its biology is well understood.

Comments are closed.