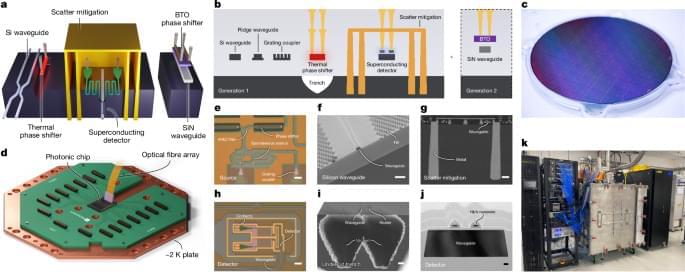

Quantum dots – semiconductor nanostructures that can emit single photons on demand – are considered among the most promising sources for photonic quantum computing.

However, every quantum dot is slightly different and may emit a slightly different color, according to a team at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, which has developed a technique to improve multi-photon state generation. The Innsbruck team states that, “the different forms of quantum dot means that, to produce multi-photon states we cannot use multiple quantum dots.”

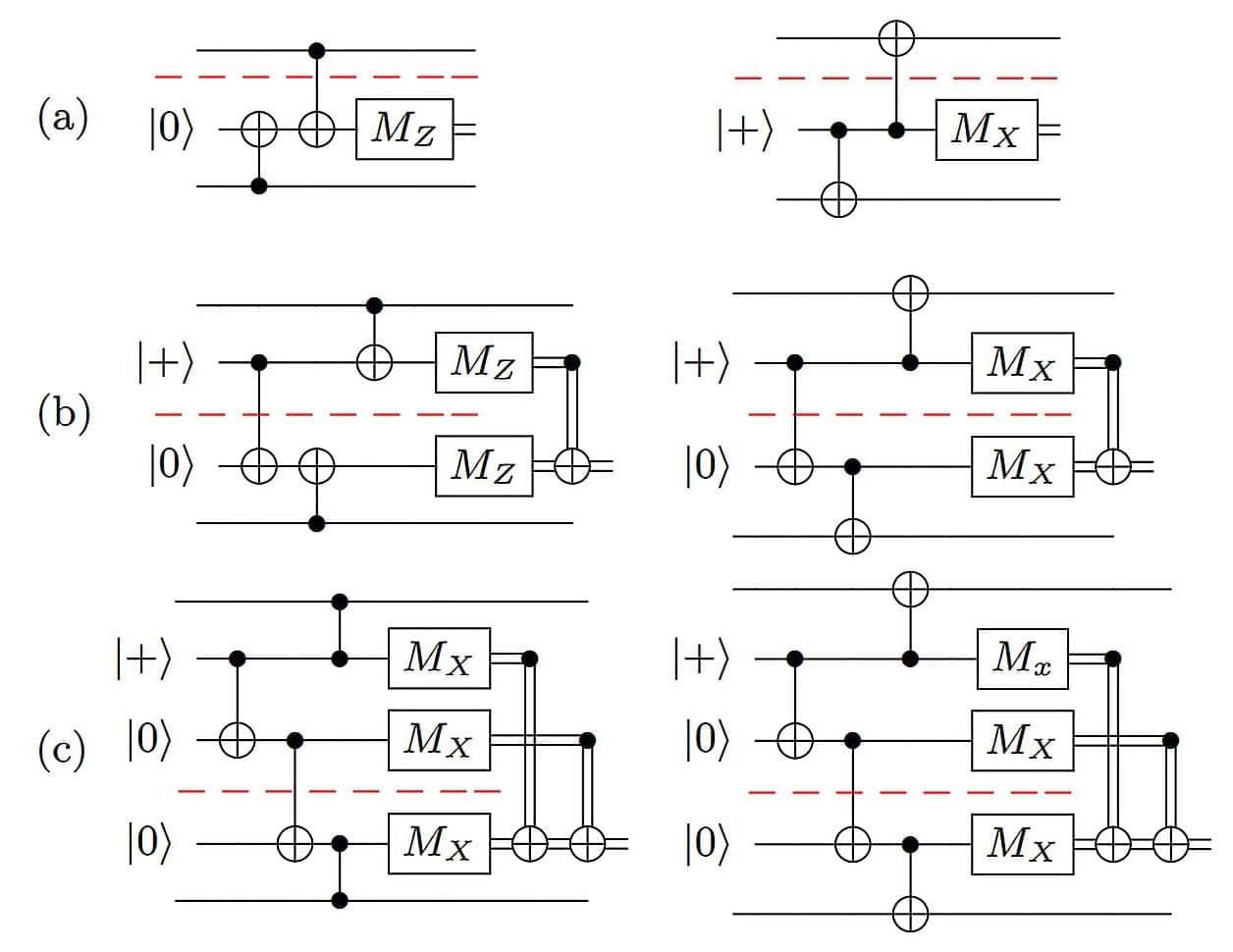

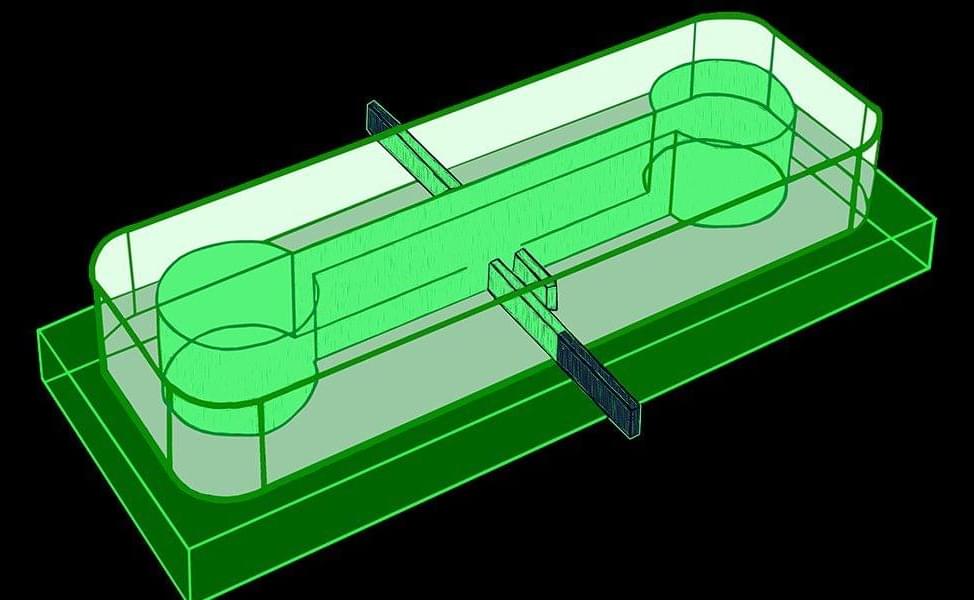

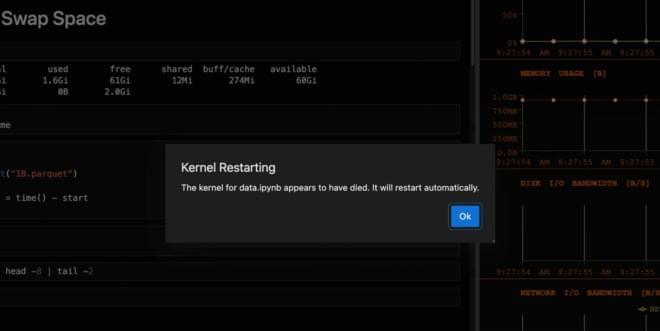

Usually, researchers use a single quantum dot and multiplex the emission into different spatial and temporal modes, using a fast electro-optic modulator. But a contemporary technological challenge: faster electro-optic modulators are expensive and often require very customized engineering. To add to that, it may not be very efficient, which introduces unwanted losses in the system.

Nature Publishing: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41534-025-01083-0

Security wise: The team’s work combines years of research in quantum optics, semiconductor physics, and photonic engineering to open the door for next-generation quantum computers andunwanted losses in the system.

Communications. Here’s what you need to know. Securities IO: https://www.securities.io/passive-two-photon-quantum-dots-secure-communication