To get the best measurements of Earth’s atmosphere, you sometimes have to leave it. This November, the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich spacecraft will do just that.

The world’s first waterproof drone capable of submerging under water, floating like a boat and flying through the air at over 40mph (60kmh) has been unveiled by US engineers.

The $765 (£585) gadget, known as Spry, features a built-in 4K camera that can both record video and snap photos on the fly.

Footage is beamed back to a monitor embedded into a waterproof remote control, which the drone’s developers claim is another world first for the drone industry.

O,.o.

Vat19 puts the life-saving LifeStraw water filter to the test by trying it out in sewage, urinal water, water from the Mississippi River, and even some liquid vomit. The video, naturally, comes with a warning for the weak of stomach.

This is our grossest video ever. If you have a weak stomach, you’ve been warned!?

Visit http://TED.com to get our entire library of TED Talks, transcripts, translations, personalized talk recommendations and more.

Hugh Herr is building the next generation of bionic limbs, robotic prosthetics inspired by nature’s own designs. Herr lost both legs in a climbing accident 30 years ago; now, as the head of the MIT Media Lab’s Biomechatronics group, he shows his incredible technology in a talk that’s both technical and deeply personal — with the help of ballroom dancer Adrianne Haslet-Davis, who lost her left leg in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, and performs again for the first time on the TED stage.

The TED Talks channel features the best talks and performances from the TED Conference, where the world’s leading thinkers and doers give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes (or less). Look for talks on Technology, Entertainment and Design — plus science, business, global issues, the arts and more. You’re welcome to link to or embed these videos, forward them to others and share these ideas with people you know. For more information on using TED for commercial purposes (e.g. employee learning, in a film or online course), submit a Media Request here: http://media-requests.TED.com

Follow TED on Twitter: http://twitter.com/TEDTalks

Like TED on Facebook: http://facebook.com/TED

We saw the Apple Watch 6 and iPad Air 4, but no iPhone 12 announced at Apple’s latest event. Here are the highlights! ⌚📱.

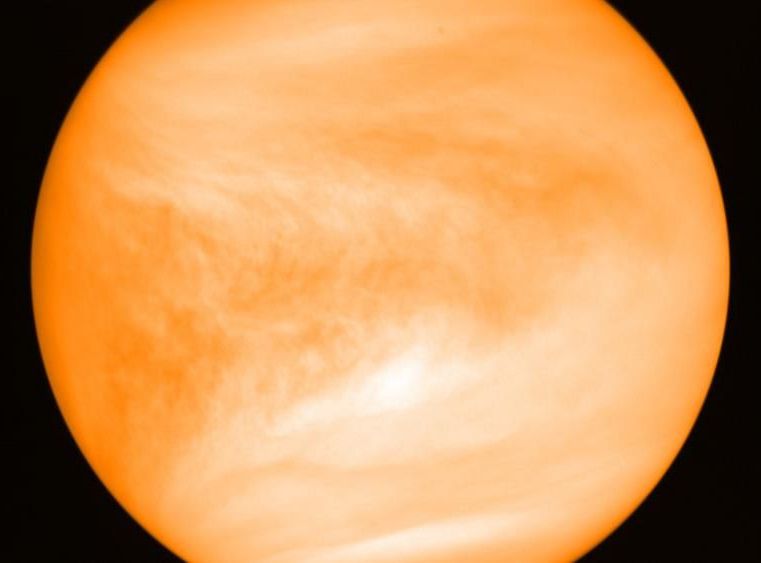

In a statement, Roscosmos noted that the first missions to explore Venus were carried out by the Soviet Union.

“The enormous gap between the Soviet Union and its competitors in the investigation of Venus contributed to the fact that the United States called Venus a Soviet planet,” Roscosmos said.

The Russians claim to have extensive material that suggests that some objects on the Venusian surface have changed places or could be alive, although these are hypotheses that have yet to be confirmed.

Russia has announced an intention to independently explore Venus a day after scientists said there was a gas that could be present in the planet’s clouds due to single-cell microbes.

The head of Russia’s space corporation Roscosmos, Dmitry Rogozin, told reporters that they would initiate a national project as “we believe that Venus is a Russian planet,” according to the TASS news agency.

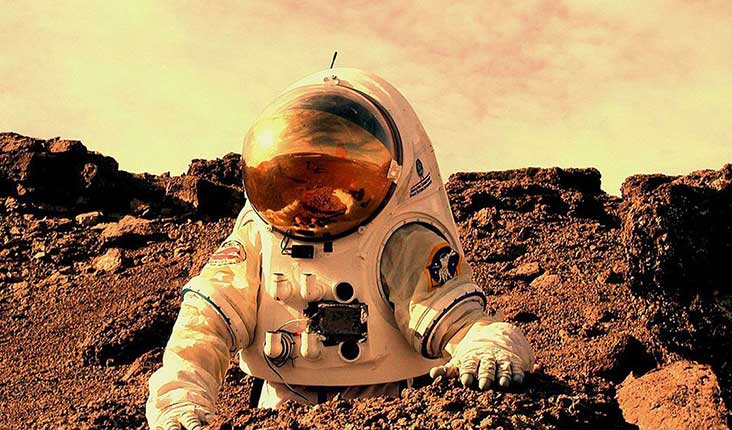

Over the past five decades, space travel advocates have been pushing to expand our footprint in space. They dream about lunar bases, missions to Mars and colonies in free space. The visions are ever changing, with government efforts joined by those of private companies like Elon Musk’s SpaceX — in the midst of an effort to send tourists on a trip around the Moon — gravitating toward the space tourism sector. While the goals and how to accomplish them are in constant flux, there remain certain obstacles that must be overcome before we take that next big step. And one of the biggest is the need to protect the health of our future space explorers.

That’s what’s prompted NASA to turn to the fast-moving world of gene therapy to solve several potential medical issues facing astronauts on lengthy space missions.

The US space agency and the associated Translational Institute for Space Health Research (TRISH) at the Baylor College of Medicine are now calling for proposals from private companies and other groups to develop a kind of gene therapy for astronauts. But this would be different than recent gene therapies that target specific diseases such as hemophilia or various types of cancer. Instead, the idea here is to minimize the damage from space radiation through a kind of preventive treatment. Exposure to radiation in space can cause cancer, cardiovascular disease, cataracts and the loss of cognitive function due to accelerated death of brain cells. These different disease categories involve very different mechanisms — cancer and heart disease result from radiation damaging DNA, while loss of brain tissue results simply from radiation killing off mature cells, and still other diseases result from radiation destroying stem cells.

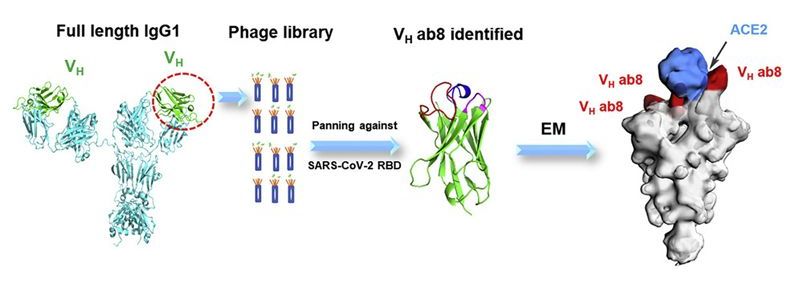

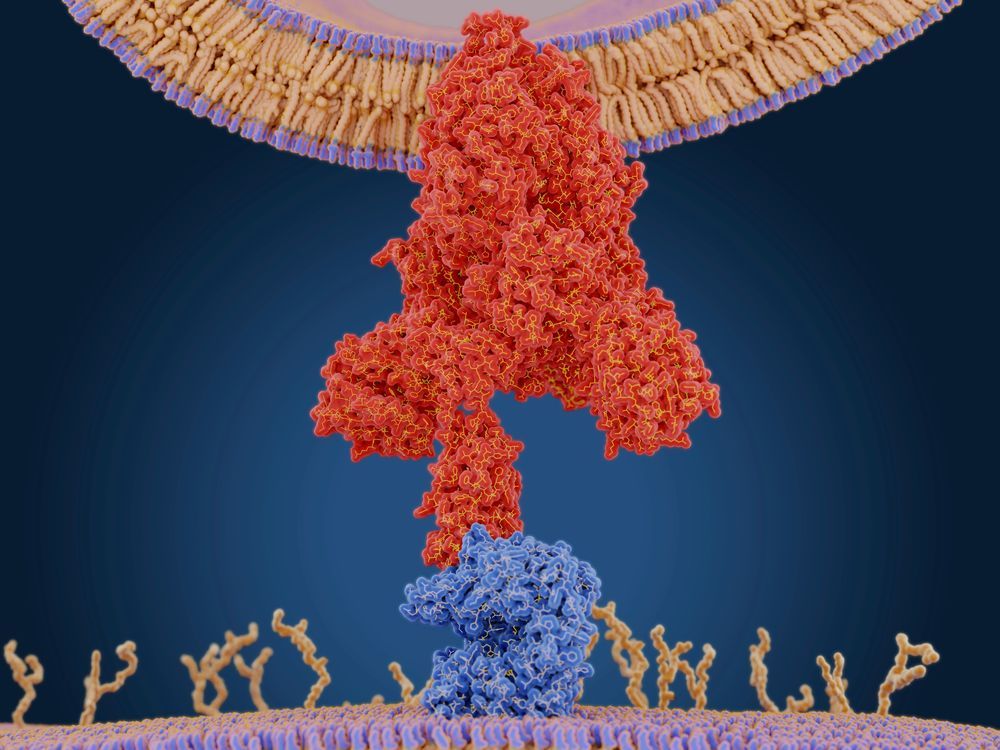

When a virus invades your cells, it changes your body. But in the process, the pathogen changes its shape, too. A new mathematical model predicts the points on the virus that allow this shape-shifting to occur, revealing a new way to find potential drug and vaccine targets. The unique math-based approach has already identified potential targets in the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Outlined in April in the Journal of Computational Biology, the strategy predicts protein sites on viruses that stash energy—important spots that drugs could disable. In a rare feat, the work proceeds from pure mathematics, says study author and mathematician Robert Penner of the Institute of Advanced Scientific Studies in France. “There’s precious little pure math in biology,” he adds. The paper’s predictions face a long road before they can be verified experimentally, says John Yin, who studies viruses at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and was not involved in the research. But he agrees that Penner’s approach has potential. “He’s coming at this from a mathematician’s point of view—but a very scientifically informed mathematician,” Yin says. “So that’s highly rare.”

Penner’s method takes advantage of the fact that certain viral proteins alter their shape dramatically when viruses breach cells, and this transformation depends on unstable features. (A stable protein site, by definition, resists change.) By identifying “high free energy sites”—areas on a viral protein that store lots of energy—Penner realized he could spot likely “spring” points that mediate this change in shape. He calls such high-energy spots exotic sites. Finding them required some complex math.

Akon has released detailed plans of Akon City, his $6 billion futuristic cryptocurrency city, which he calls a “real-life Wakanda,” referring to the hit movie Black Panther. There will be seven major districts, and the city will be run on the akoin cryptocurrency.

Senegalese-American star and philanthropist Akon, whose full name is Aliaune Damala Badara Akon Thiam, unveiled Monday some major details of his planned Akon City. The $6 billion futuristic city in Senegal, Africa, will be run on the akoin cryptocurrency.

The city will be divided into seven major districts: the African culture village district, the offices and residential district, the entertainment district, the health and safety district, the education district, the technology district, and the Senewood district.