Meet Ford’s new delivery bot 😃

Ford partnered with Agility Robotics to create Digit, a two-legged robot that could deliver your packages straight to your door in the future.

Here it is, part one of my new trilogy…Sleep Deprivation…it’s a killer. Personally, I used to miss whole nights clubbing and gigging, and even after that, I used to cut back the hours of sleep thinking I was getting the most from my life and being really clever. Then I heard of Matthew Walker, and read his book. I changed immediately and wow, I have never felt such a difference, it is like light and day. Every aspect of my life improved, from mental health, to physical wellbeing, to immune function (I never seem to be ill any more and never get cold sores!!! anecdotal but the truth). The most telling fact. If I tried to drive more than a couple of hours down the motorway I would be fighting to keep my eyes open by the end…now, that is never a problem (although I still want a Tesla). Sleep is now what I consider a non-negotiable. It comes first. It is the foundation on which everything else stands.

I will just break down exactly why depriving yourself of sleep is a fools errand. You may gain a hour or two here and there, but it does not compare to the years it wipes off your lifespan, and even worse the decrepit, run down years of pain and inactivity that blight the end decades.

All that pain, when you could be fully active and fulfilling your dreams and ambitions.

If you want to try Melatonin to aid your sleep, or any other of their products, I have arranged a discount for my friends and viewers at Do Not Age, the highest quality, the lowest prices and the best customer service, all in one place.

Just use the code MTB when checking out.

https://donotage.org.

And if you want to watch how stress effects the body and the evolution that set it all in motion, then you might find this video of interest.

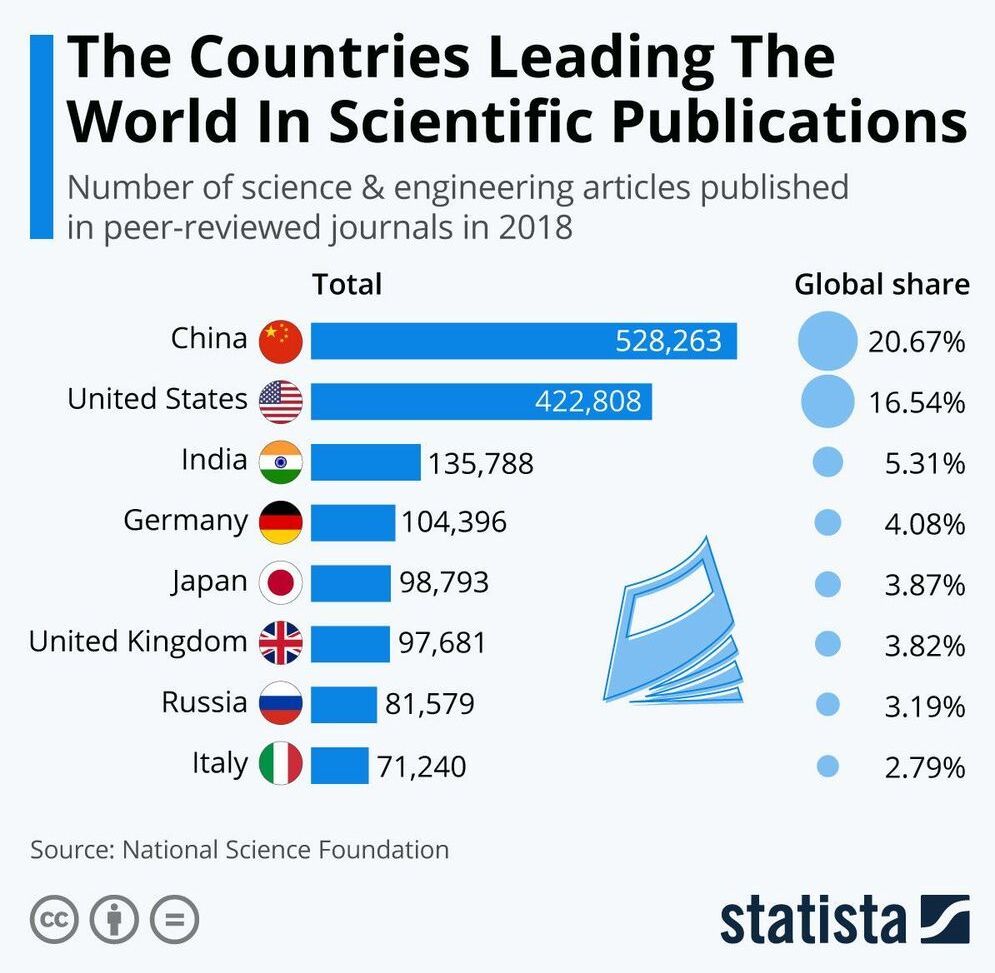

China keeps leading the US on investments in tech.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) has released data showing that 2555, 959 science and engineering (S&E) articles were published around the world in 2018, a considerable increase on the 1755, 850 recorded a decade ago. Global research output in that sector has grown around 4 percent annually over the past ten years and China’s growth rate is notable as being twice the world average. While the U.S. led the way in 2008, it has now been displaced as the world’s top S&E research publisher by China.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

This video explains post translational modifications of proteins.

Thank You For Watching.

Please Like And Subscribe to Our Channel: https://www.youtube.com/EasyPeasyLearning.

Like Our Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/learningeasypeasy/

Join Our Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/460057834950033

The Chinese government formed Comac in 2008 to design and build the single-aisle C919.

However, most of the parts are imported from foreign manufacturers, including the engine, avionics, control systems, communications and landing gear.

China’s government formed the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (Comac) in 2008 to design and construct the single-aisle C919 to reduce reliance on Europe’s Airbus and the United States’ Boeing.

Will humanity ever travel to the stars? This is a question for the ages and it remains as open as a deserted stretch of interstate highway. To answer this question, we need an international scientifically-based effort that can chip away at the physics needed to make Star Trek real. Please have a listen to this episode with Guest Marc Millis. Well worth your time.

Propulsion physicist Marc Millis talks about the prospects for fast, efficient interstellar travel. Millis was head of NASA’s Breakthrough Propulsion Program at Glenn Research Center outside Cleveland for years beginning in the mid-1990s. We discuss why the problem of traveling to the stars is so difficult and what would need to happen to help such dreams become a reality. It’s a lively and irreverent discussion!

Science and Futurism with Isaac Arthur is a YouTube channel which focuses on exploring the depths of concepts in science and futurism. Since its first episode in 2014, SFIA has considered topics ranging from the seemingly mundane, to the extremely exotic, featuring episodes on megastructure engineering, interstellar travel, the future of earth, and the Fermi paradox, among others. Yet regardless of how strange a subject may seem, Isaac always tries to ensure that the discussion is grounded in the known science of today.

Isaac Arthur joins John Michael Godlier on today’s Event Horizon to discuss these subjects, the future past 2020. Thoughts on life extension. Nanotechnology. Artificial intelligence. The Fermi paradox.

What is the most obvious answer to the Fermi paradox?

Science and Futurism with Isaac Arthur: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZFipeZtQM5CKUjx6grh54g.

Want to support the channel?

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/EventHorizonShow.

Follow us at other places!