Amid unrelenting chaos and violence, scientists and doctors in the Democratic Republic of Congo have been running a clinical trial of new drugs to try to combat a year-long Ebola outbreak. On Monday, the trial’s cosponsors at the World Health Organization and the National Institutes of Health announced that two of the experimental treatments appear to dramatically boost survival rates.

While an experimental vaccine previously had been shown to shield people from catching Ebola, the news marks a first for people who already have been infected. “From now on, we will no longer say that Ebola is incurable,” said Jean-Jacques Muyembe, director general of the Institut National de Recherche Biomedicale in the DRC, which has overseen the trial’s operations on the ground.

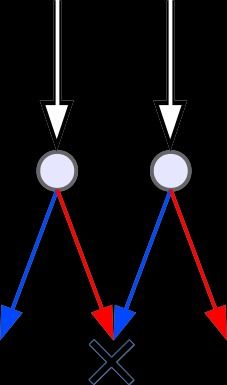

Starting last November, patients in four treatment centers in the country’s east, where the outbreak is at its worst, were randomly assigned to receive one of four investigational therapies—either an antiviral drug called remdesivir or one of three drugs that use monoclonal antibodies. Scientists concocted these big, Y-shaped proteins to recognize the specific shapes of invading bacteria and viruses and then recruit immune cells to attack those pathogens. One of these, a drug called ZMapp, is currently considered the standard of care during Ebola outbreaks. It had been tested and used during the devastating Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014, and the goal was to see if those other drugs could outperform it. But preliminary data from the first 681 patients (out of a planned 725) showed such strong results that the trial has now been stopped.