By combining the language of groups with that of geometry and linear algebra, Marius Sophus Lie created one of math’s most powerful tools.

“The most striking thing was the high dust levels,” said Dr. Eva Dock.

What risks can metal recycling pose to workers? This is what a recent study published in the International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health hopes to address as a collaborative team of researchers from Sweden investigated metal and dust exposure to recycling workers. This study holds the potential to help scientists, legislators, and the public better understand the risks of metal recycling as a means for enhancing green technologies.

For the study, the researchers analyzed observation and questionnaire data obtained from 139 recycling workers across 13 Swedish metal recycling companies. Additionally, the team obtained dust and metal samples to ascertain employee exposure and biological samples, including blood and urine, to ascertain individual metal and dust exposure. The goal of the study was to ascertain the efficacy of safety protocols and the severity of exposure to employees.

In the end, the researchers discovered alarming results, including 19 percent of the employees discovered to have heightened levels of more than 10 metals within their body and 94 having heightened levels of six metals. Of the 139 employees, 32 percent were involved in e-waste recycling, while safety protocols to mitigate dust exposure were discovered to be less than satisfactory, specifically regarding the use of respiratory equipment or hygiene protocols.

Benjamin D. Humphreys provides an Editor’s Note on Christine V. Behm et al. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI197807

The figure from Behm et al. shows nephrocalcinosis in older kidney-specific Cldn2-KO mice.

Deposits of hydroxyapatite called Randall’s plaques are found in the renal papilla of calcium oxalate kidney stone formers and likely serve as the nidus for stone formation, but their pathogenesis is unknown. Claudin-2 is a paracellular ion channel that mediates calcium reabsorption in the renal proximal tubule. To investigate the role of renal claudin-2, we generated kidney tubule–specific claudin-2 conditional KO mice (KS-Cldn2 KO). KS-Cldn2 KO mice exhibited transient hypercalciuria in early life. Normalization of urine calcium was accompanied by a compensatory increase in expression and function of renal tubule calcium transporters, including in the thick ascending limb. Despite normocalciuria, KS-Cldn2 KO mice developed papillary hydroxyapatite deposits, beginning at 6 months of age, that resembled Randall’s plaques and tubule plugs.

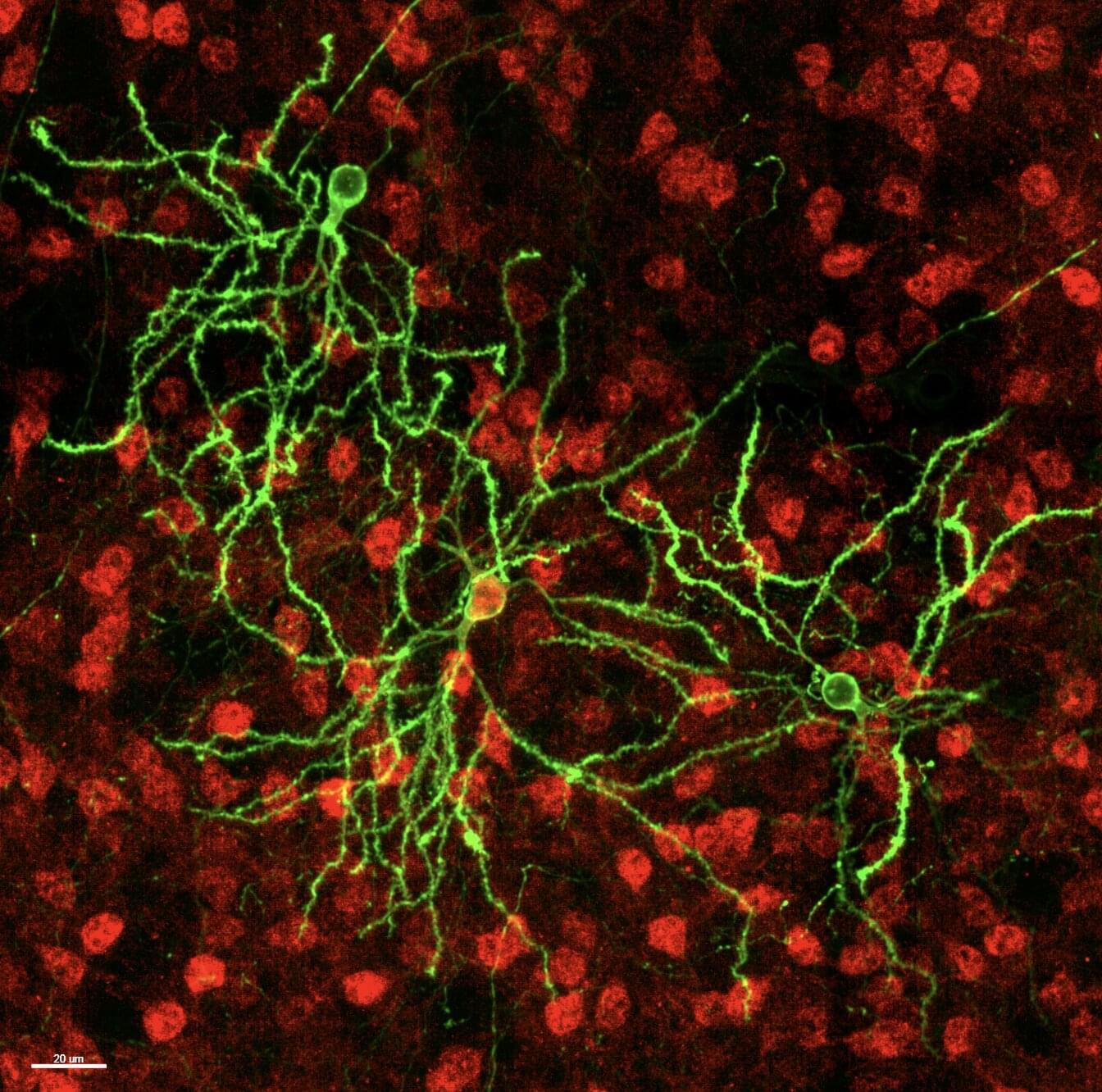

Leiden researchers can now visualize the connections between brain cells. Their microscopy technique could significantly advance the human quest to understand brain functions. The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

How does information flow through the brain? To understand this, researchers map the brain at every scale, from small networks of cells to the entire nervous system. This provides insight into how our brains work and how connections between cells may become disrupted in disease.

The research group led by Professor Sense Jan van der Molen uses a microscope that reveals how a brain structure is built. It can do so down to the level of a synapse, the tiny junction through which one neuron communicates with another cell.

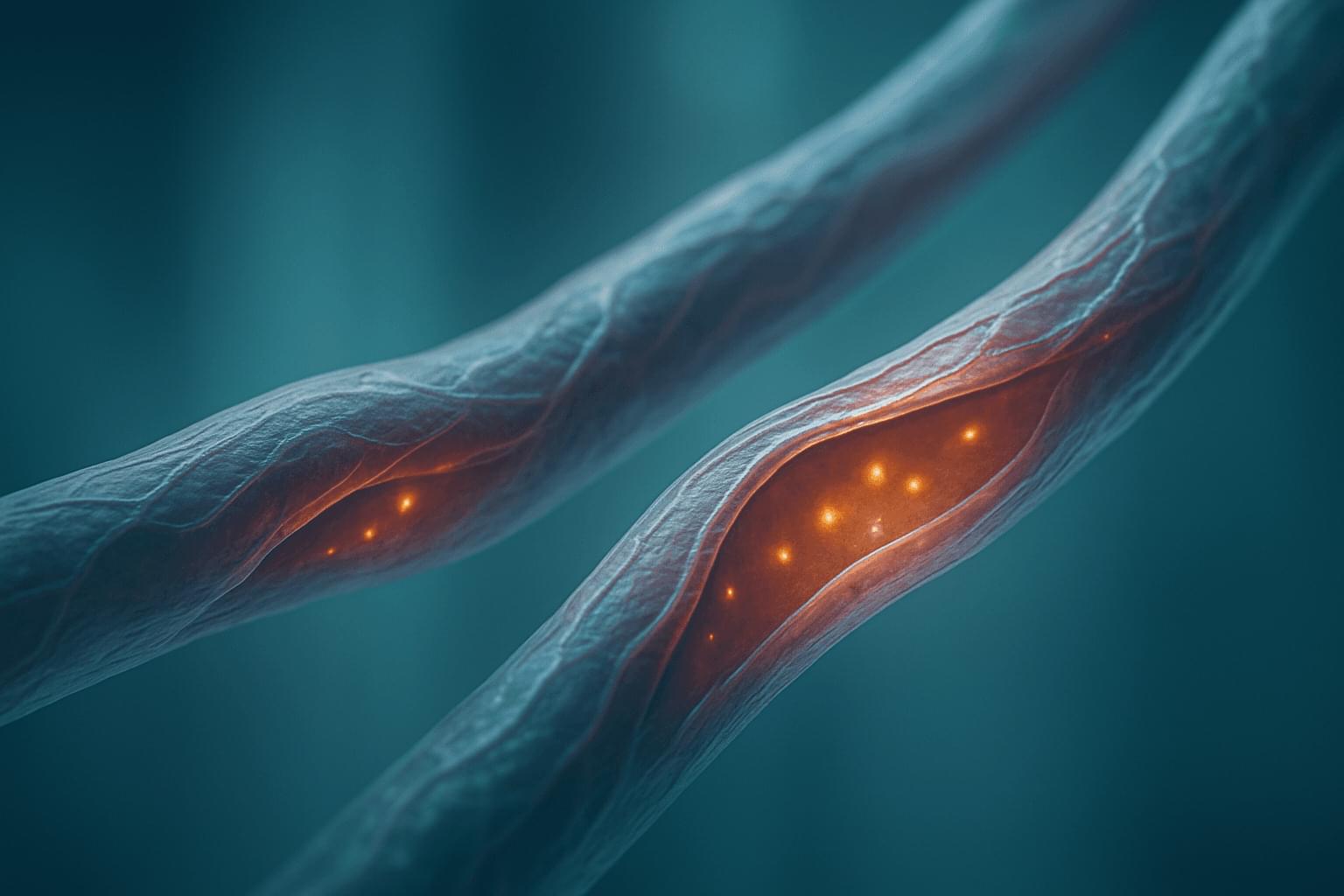

A new study shows that children born preterm who are later diagnosed with autism often present with more extensive support needs and a higher number of co-occurring conditions than autistic children born at full term. Surprisingly, however, the researchers found no differences in genetic variants across the genome, nor in specific genes already linked to autism, between the groups—a result that contradicted their initial hypothesis.

The study was conducted at KIND (Center of Neurodevelopmental Disorders at Karolinska Institutet) and published in October 2025 in the journal Genome Medicine.

“We did not observe any genetic differences between preterm and full-term autistic children, which was unexpected. We initially thought that preterm children might show fewer of the genetic factors associated with autism, as their early birth can be viewed as an environmental factor,” says Yali Zhang, doctoral student at Tammimies research group at KIND and first author of the study.

Understanding the shape or morphology of neurons and mapping the tree-like branches via which they receive signals from other cells (i.e., dendrites) is a long-standing objective of neuroscience research. Ultimately, this can help to shed light on how information flows through the brain and pin-point differences associated with specific neurological or psychiatric disorders.

The X. William Yang Lab at the Jane and Terry Semel Institute and the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have devised new sophisticated methods to map neuronal dendrites in the mouse brain, which combine large-scale data collection with genetic labeling techniques and computational tools.

Their research approach, outlined in a paper published in Nature Neuroscience, allowed them to create a comprehensive map of two genetic types of neurons in the mouse brain, known as D1-and D2-type striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs).

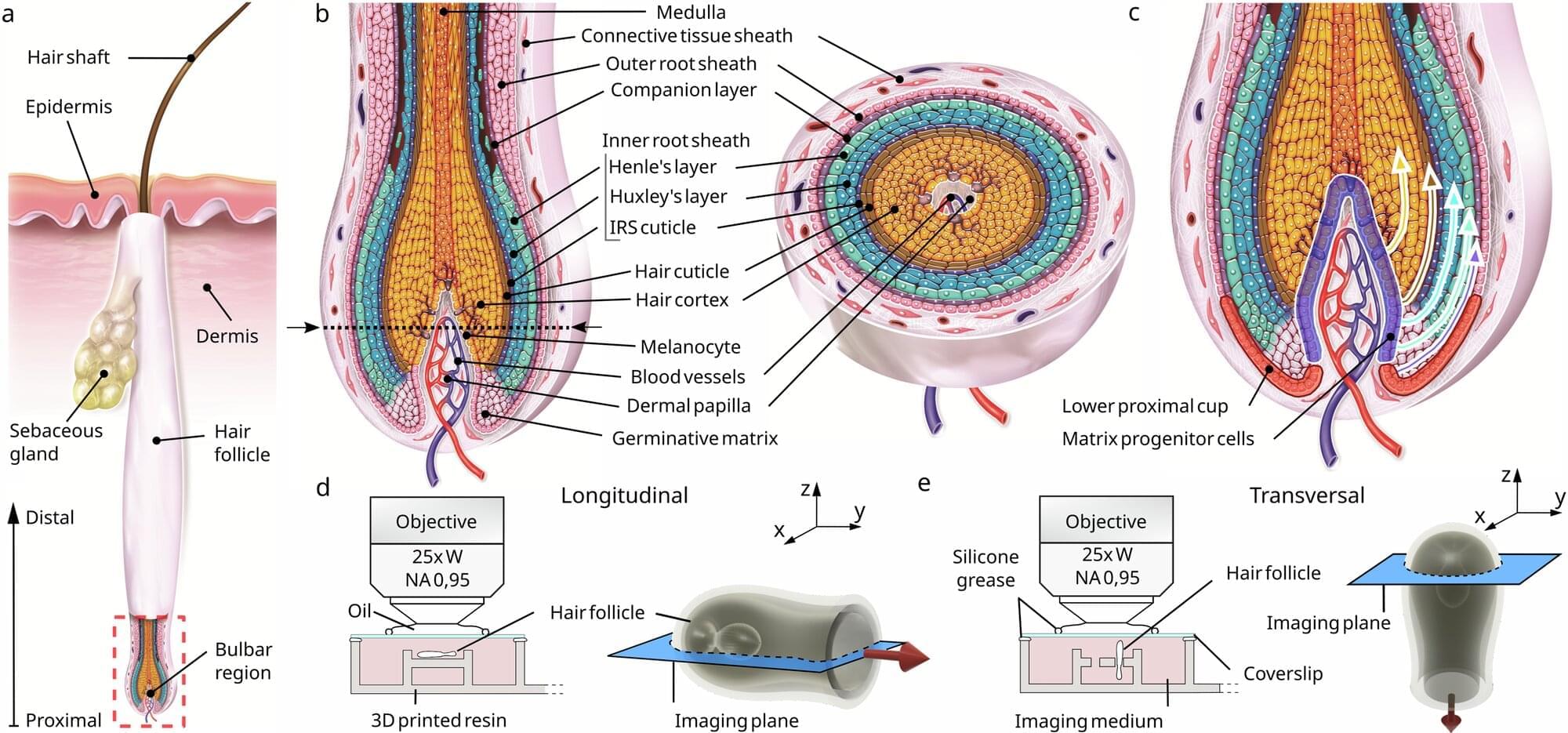

Scientists have found that human hair growth does not grow by being pushed out of the root; it’s actually pulled upward by a force associated with a hidden network of moving cells. The findings challenge decades of textbook biology and could reshape how researchers think about hair loss and regeneration.

The team, from L’Oréal Research & Innovation and Queen Mary University of London, used advanced 3D live imaging to track individual cells within living human hair follicles kept alive in culture. The study, published in Nature Communications, shows that cells in the outer root sheath—a layer encasing the hair shaft—move in a spiral downward path within the same region from where the upward pulling force originates.

Dr. Inês Sequeira, Reader in Oral and Skin Biology at Queen Mary and one of the lead authors, said, “Our results reveal a fascinating choreography inside the hair follicle. For decades, it was assumed that hair was pushed out by the dividing cells in the hair bulb. We found that instead that it’s actively being pulled upwards by surrounding tissue acting almost like a tiny motor.”

A new theory for the origins of dark matter suggests that fast-moving, neutrino-like dark particles could have decoupled from Standard Model particles far earlier than previous theories had suggested.

Through new research published in Physical Review Letters, a team led by Stephen Henrich and Keith Olive at the University of Minnesota proposes that this “ultra-relativistic freeze-out” mechanism could have produced dark matter particles which are almost undetectable, but still compatible with the observed history of the universe.

Despite comprising some 85% of the universe’s total mass, dark matter has never been seen to interact with regular matter except via gravity, making its origins one of the most enduring mysteries in cosmology.