Circa 2019

Domestic cats (Felis catus) and dogs (Canis familiaris) are the most popular companion animals; worldwide, over 600 million cats live with humans1, and in some countries their number equals or exceeds the number of dogs (e.g., Japan: dogs: 8,920,000, cats: 9,526,000)2,3. Cats started to cohabit with humans about 9,500 years ago4; their history of cohabitation with humans is shorter than that of dogs5, and they have been domesticated by natural selection, not by artificial selection6,7,8. Despite these differences in their process of domestication compared to that of dogs, cats too have developed behaviours related to communication with humans; for example, for human listeners, the vocalisations of domestic cats are more comfortable than those of African wild cats (Felis silvestris lybica)9. In addition, purring has different acoustical components during solicitation of foods than at other times, and humans perceive such solicitation purrs as more urgent and unpleasant than non-solicitation purrs10. These facts clearly indicate that domestic cats have developed the ability to communicate with humans and frequently do so; Bradshaw8 suggested that this inter-species communicative ability is descended from intra-species communicative ability.

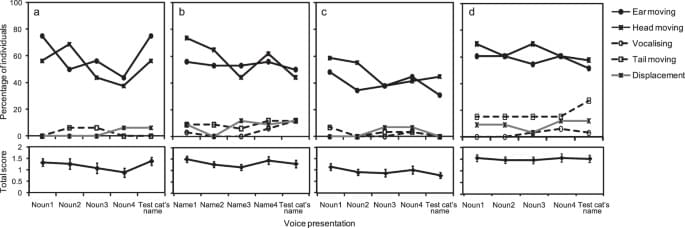

Researchers have only recently begun to investigate cats’ ability to communicate with humans. Miklósi et al. showed that cats are able to use the human pointing gesture as a cue to find hidden food, similarly to dogs11. The researchers also suggested that cats do not gaze toward humans when they cannot access food, unlike dogs. However, a recent study revealed that cats show social referencing behaviour (gazing at human face) when exposed to a potentially frightening object, and to some extent cats changed their behaviour depending on the facial expression of their owner (positive or negative)12. Cats in food begging situations can also discriminate the attentional states of humans who look at and call to them13. In addition, Galvan and Vonk demonstrated that cats were modestly sensitive to their owner’s emotions14, and other research has indicated that cats’ behaviour is influenced by human mood15,16. Further, cats can discriminate their owner’s voice from a stranger’s17. This research evidence illustrates that domestic cats have the ability to recognize human gestural, facial, and vocal cues.

In contrast to cats, numerous research studies have shown the ability of domestic dogs to communicate with humans. Dogs are skilful at reading human communicative gestures, such as pointing (reviewed in Miklósi & Soproni18). Dogs can differentiate human attentional states19,20,21,22 and distinguish human smiling faces from blank expressions23. They are also capable of using some human emotional expressions to help them find hidden food and fetch objects24,25.