IBM researchers have succeeded in guiding visible light through a silicon wire efficiently, an important milestone in the exploration towards a new breed of faster, more efficient logic circuits.

CARSON CITY, Nev. (AP) — In the Nevada desert, a cryptocurrency magnate hopes to turn dreams of a futuristic “smart city” into reality. To do that, he’s asking the state to let companies like his form local governments on land they own, which would grant them power over everything from schools to law enforcement.

Jeffrey Berns, CEO of Nevada-based Blockchains LLC, envisions a city where people not only purchase goods and services with digital currency but also log their entire online footprint — financial statements, medical records and personal data — on blockchain. Blockchain is a digital ledger known mostly for recording cryptocurrency transactions but also has been adopted by some local governments for everything from documenting marriage licenses to facilitating elections.

The company wants to break ground by 2022 in rural Storey County, 12 miles (19 kilometers) east of Reno. It’s proposing to build 15000 homes and 33 million square feet (3 million square meters) of commercial and industrial space within 75 years. Berns, whose idea is the basis for draft legislation that some lawmakers saw behind closed doors last week, said traditional government doesn’t offer enough flexibility to create a community where people can invent new uses for this technology.

NASA to fly a helicopter on Mars

Posted in space

It’s never easy. It’s always exciting. Our next Mars landing happens on Feb. 18, and you’re invited to take part as NASA’s Perseverance Mars Rover begins its exploration of mysterious Jezero Crater. Here’s how to join in the # CountdownToMars : http://go.nasa.gov/3tVrB8T

2021 view of Mars just got released

Posted in space

On the 12th of January 2021, NASA released the last panorama of Mars captured by the Curiosity Rover near Mount Sharp. This spectacular view presented on the highest quality is a combination of 122 photos.

Days ago, Insight Lander ended Its journey on Mars. In February Perseverance Rover will begin its trip!

Enjoy this mesmerizing view on Mars, with interesting details explained in this video!

After an aborted test in December, Richard Branson’s company will try again from New Mexico.

🛡World’s First EMP Defense Technology. Protects Your Entire Home’s Electrical System!

🔥Available to the Public Now!

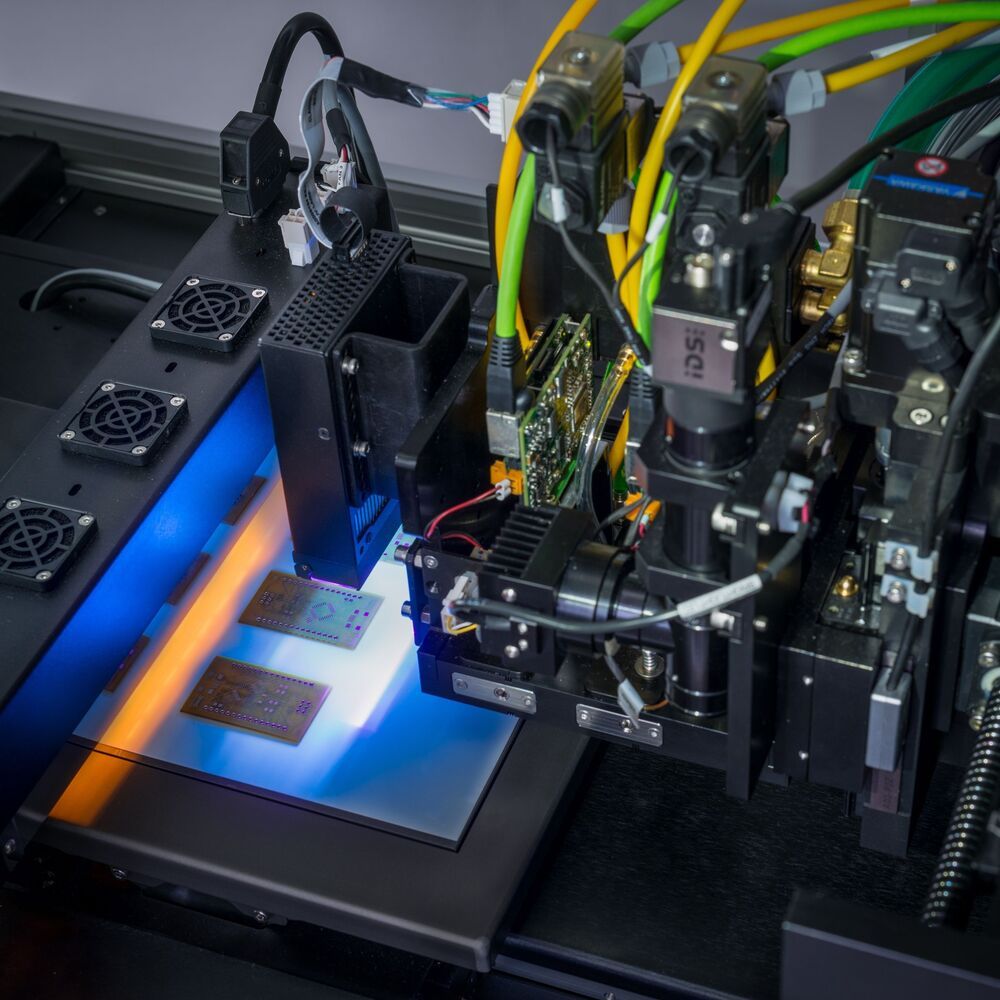

Since its proprietary technology launched back in 2014, industrial 3D printer OEM Nano Dimension has built a name for itself in the world of additively manufactured electronics (AME).

With ongoing refinements to its flagship DragonFly LDM® 3D printer, the company is now doubling down on its 3D printing of high-performance electronic devices (Hi-PEDs™), an area in which it’s seen significant success in recent years. The Hi-PEDs™ targeted by the company often cannot be produced using traditional printed circuit board (PCB) manufacturing processes.

Yoav Stern, CEO of Nano Dimension, states, “We’re the 3D printing company for customers who need to stay on the cutting edge of electronics design. You’re creating the latest innovations in hardware development and electronic circuits. You need an additive manufacturing solution that allows you to go where no one has gone before in electronics design — and to get there faster and easier than ever before.”

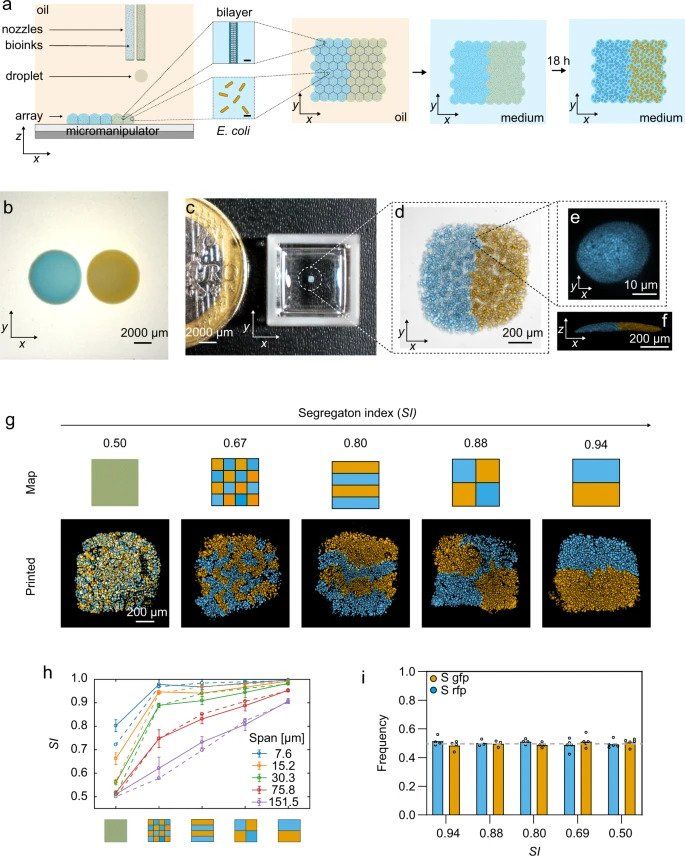

Researchers from the University of Oxford have developed a droplet-based 3D printing method capable of customizing bacterial genotypes at the micron-scale, which could drive major shifts in ecology.

Using droplet printing, the researchers were able to print strains of the gut bacterium Escherichia coli, also known as E. coli, and alter its spacing to create customized communities of the bacteria in order to see how strains react to each other when placed side-by-side in specific patterns.

Being able to manipulate the arrangement of such bacteria at the micron-scale enables greater observation and understanding of its behavior, and could even be “critical for ecological outcomes”, the researchers claim.