Imagine a road with two lanes in each direction. One lane is for slow cars, and the other is for fast ones. For electrons moving along a quantum wire, researchers in Cambridge and Frankfurt have discovered that there are also two “lanes,” but electrons can take both at the same time!

Current in a wire is carried by the flow of electrons. When the wire is very narrow (one-dimensional, 1D) then electrons cannot overtake each other, as they strongly repel each other. Current, or energy, is carried instead by waves of compression as one particle pushes on the next.

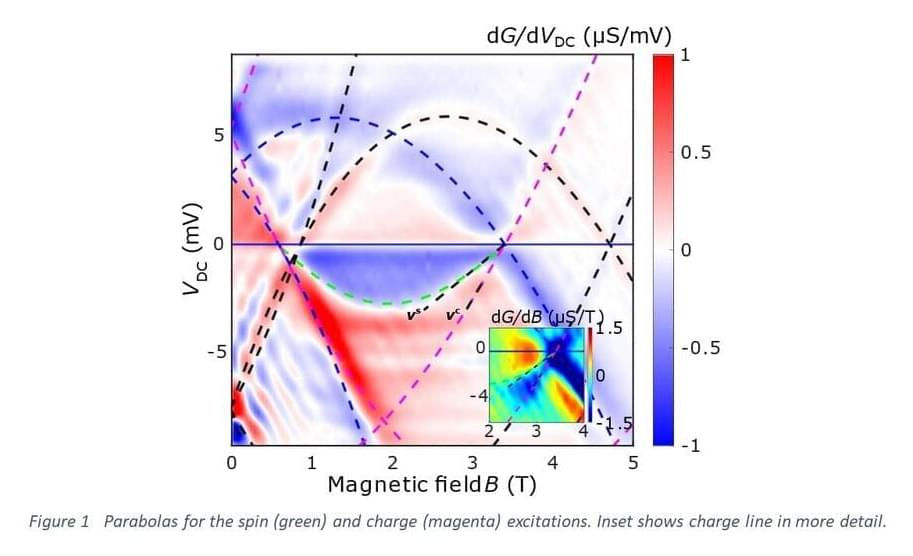

It has long been known that there are two types of excitation for electrons, as in addition to their charge they have a property called spin. Spin and charge excitations travel at fixed, but different speeds, as predicted by the Tomonaga-Luttinger model many decades ago. However, theorists are unable to calculate what precisely happens beyond only small perturbations, as the interactions are too complex. The Cambridge team has measured these speeds as their energies are varied, and find that a very simple picture emerges (now published in the journal Science Advances). Each type of excitation can have low or high kinetic energy, like cars on a road, with the well-known formula E=1/2 mv2, which is a parabola. But for spin and charge the masses m are different, and, since charges repel and so cannot occupy the same state as another charge, there is twice as wide a range of momentum for charge as for spin.