Despite constituting less than 2% of the body’s mass, the human brain consumes approximately 20% of total caloric intake, with 50% of the energy being used by cortex (Herculano-Houzel, 2011). The majority of this energy is spent by neurons to reverse the ion fluxes associated with electrical signaling via Na+/K+ ATPase (Attwell and Laughlin, 2001; Harris et al., 2012). Excitatory synaptic currents and action potentials are particularly costly in this regard, accounting for approximately 57% and 23% of the energy budget for electrical signaling in gray matter, respectively (Harris et al., 2012; Sengupta et al., 2010). Given this cost, and the scarcity of resources, the brain is thought to have evolved an energy-efficient coding strategy that maximizes information transmission per unit energy (i.e., ATP) (Barlow, 2012; Levy and Baxter, 1996). This strategy accounts for a number of cellular features, including the low mean firing rate of neurons and the high failure rate of synaptic transmission, as well as higher order features, such as the structure of neuronal receptive fields (Albert et al., 2008; Attwell and Laughlin, 2001; Harris et al., 2015; Levy and Baxter, 1996; Olshausen and Field, 1997; Sterling and Laughlin, 2015). Scarcity of food, therefore, appears to have strongly sculpted information coding in the brain throughout evolution.

Energy intake is not fixed but can vary substantially across individuals, environments, and time (Hladik, 1988; Knott, 1998). Given that the brain is energy limited, one hypothesis is that in times of food scarcity, neuronal networks should save energy by reducing information processing. There is some evidence to suggest that this is the case in invertebrates (Kauffman et al., 2010; Longden et al., 2014; Plaçais et al., 2017; Placais and Preat, 2013). In Drosophila 0, food deprivation inactivates neural pathways required for long-term memory to preserve energy (Plaçais et al., 2017; Placais and Preat, 2013). Experimental re-activation of these pathways restores memory formation but significantly reduces survival rates (Placais and Preat, 2013). Similar memory impairments are seen with reduced food intake in C. elegans (Kauffman et al., 2010). Moreover, in blowfly, food deprivation reduces visual interneuron responses during locomotion, consistent with energy savings (Longden et al., 2014). However, it remains unclear whether and how the mammalian brain, and cortical networks in particular, regulate information processing and energy use in times of food scarcity.

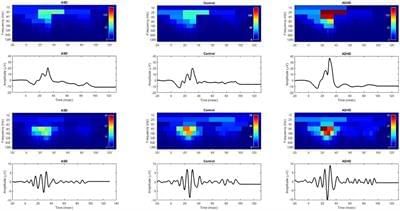

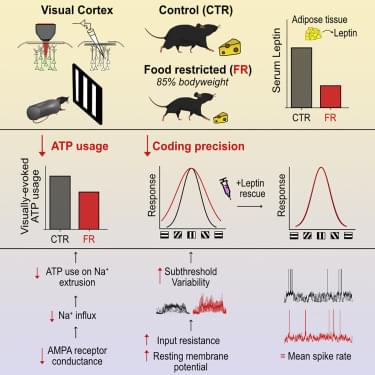

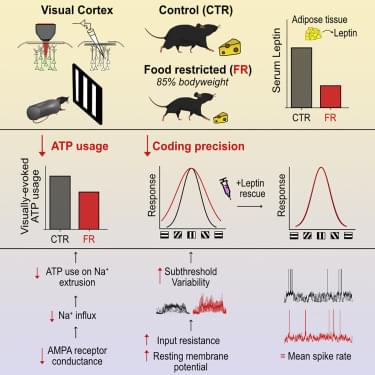

Here we used the mouse primary visual cortex (V1) as a model system to examine how food restriction affects information coding and energy consumption in cortical networks. We assessed neuronal activity and ATP consumption using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings and two-photon imaging of V1 layer 2/3 excitatory neurons in awake, male mice. We found that food restriction, resulting in a 15% reduction of body weight, led to a 29% reduction in ATP expenditure associated with excitatory postsynaptic currents, which was mediated by a decrease in single-channel AMPA receptor (AMPAR) conductance. Reductions in AMPAR current were compensated by an increase in input resistance and a depolarization of the resting membrane potential, which preserved neuronal excitability; neurons were therefore able to generate a comparable rate of spiking as controls, while spending less ATP on the underlying excitatory currents. This energy-saving strategy, however, had a cost to coding precision. Indeed, we found that an increase in input resistance and depolarization of the resting membrane potential also increased the subthreshold variability of visual responses, which increased the probability for small depolarizations to cross spike threshold, leading to a broadening of orientation tuning by 32%. Broadened tuning was associated with reduced coding precision of natural scenes and behavioral impairment in fine visual discrimination. We found that these deficits in visual coding under food restriction correlated with reduced circulating levels of leptin, a hormone secreted by adipocytes in proportion to fat mass (Baile et al., 2000), and were restored by exogenous leptin supplementation. Our findings reveal key metabolic state-dependent mechanisms by which the mammalian cortex regulates coding precision to preserve energy in times of food scarcity.