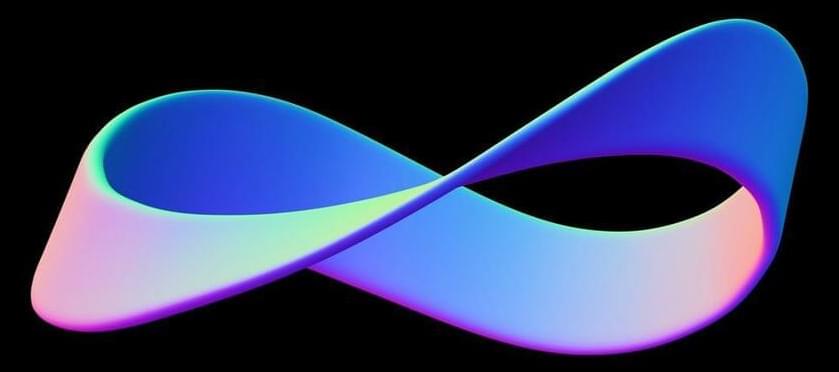

Möbius strips are fun geometrical shapes that only have one side. Take a strip of paper – it’s got a front and a back. Now twist it and glue the two short edges together. Suddenly there is no front or back. You could draw a line across its whole surface without having to lift the pencil from the paper. Forty-six years ago mathematicians suggested the minimum size for such a strip but they couldn’t prove it. Now, someone finally has.

Since the creation of the strip by August Ferdinand Möbius and Johann Benedict Listing, its simplicity in making and visualizing it had to be balanced with the mathematical complexity of such a shape. It is not surprising that in 1977, Charles Sidney Weaver and Benjamin Rigler Halpern created the Halpern-Weaver Conjecture, which stated the minimal ratio between the width of the strip and its length. They suggested that for a strip with a width of 1 centimeter (0.39 inches), the length had to be at least the square root of 3 centimeters (about 1.73 centimeters or 0.68 inches).

For smooth Möbius strips that are “embedded”, meaning they don’t intersect with each other, the conjecture had no solution. If the strip can go through itself, it is a much easier problem to solve, Brown University’s mathematician Richard Evan Schwartz proposed in 2020 – but he had made a mistake. In a paper posted as a preprint – meaning it is yet to be subjected to peer review – Schwartz corrected the error and found the right solution for the conjecture.