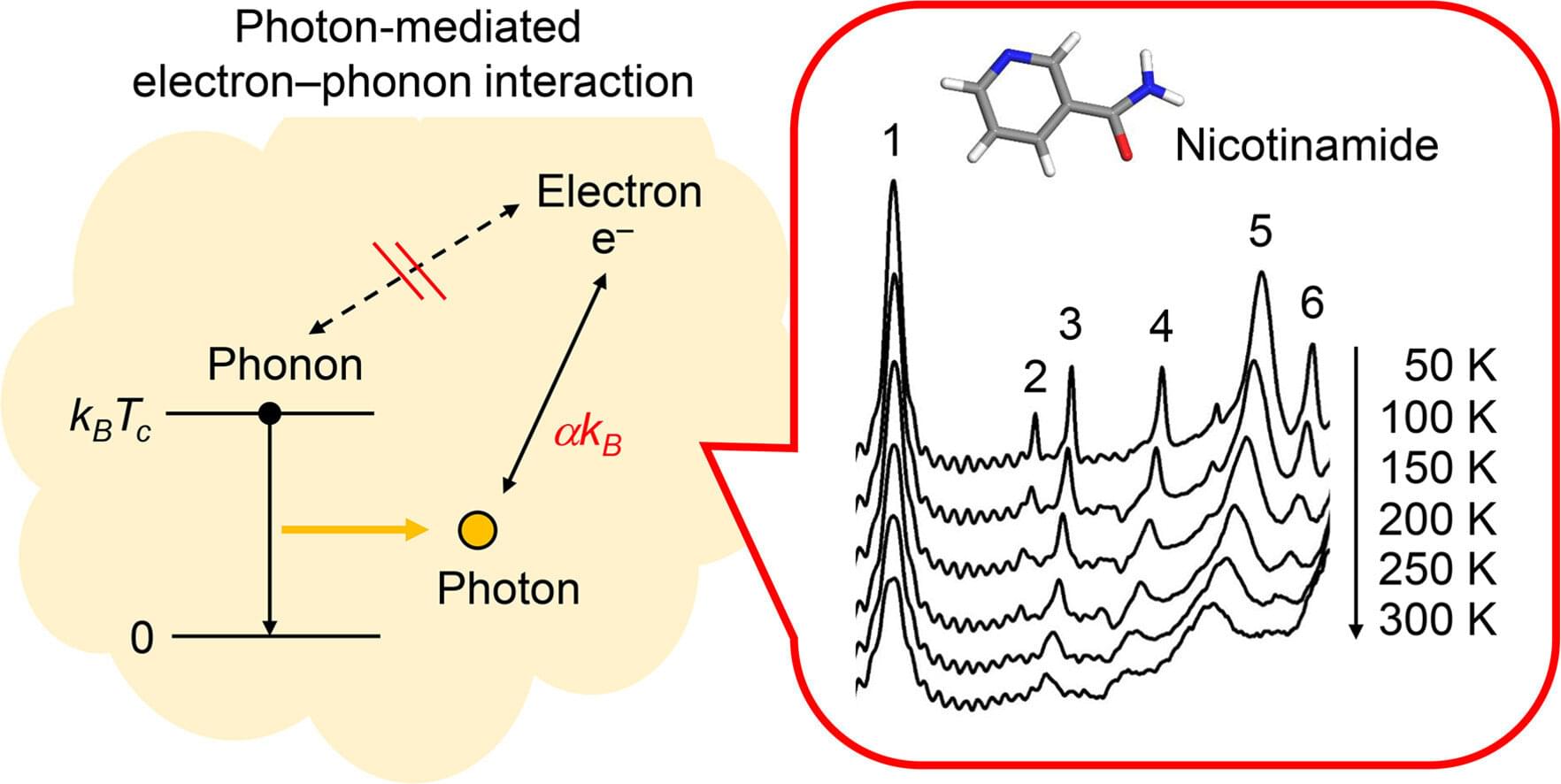

A researcher at the Department of Physics at Tohoku University has uncovered a surprising quantum phenomenon hidden inside ordinary crystals: the strength of interactions between electrons and lattice vibrations—known as phonons—is not continuous, but quantized. Even more remarkably, this strength is universally linked to one of the most iconic numbers in physics: the fine-structure constant.

What makes this dimensionless number (α ≈ 1/137) so iconic is its ability to explain electromagnetic interactions, independent of the units used. Imagine it like a ratio where one pencil is twice as long as another pencil—this ratio won’t change no matter whether you measure the pencil length in cm, inches, or feet.