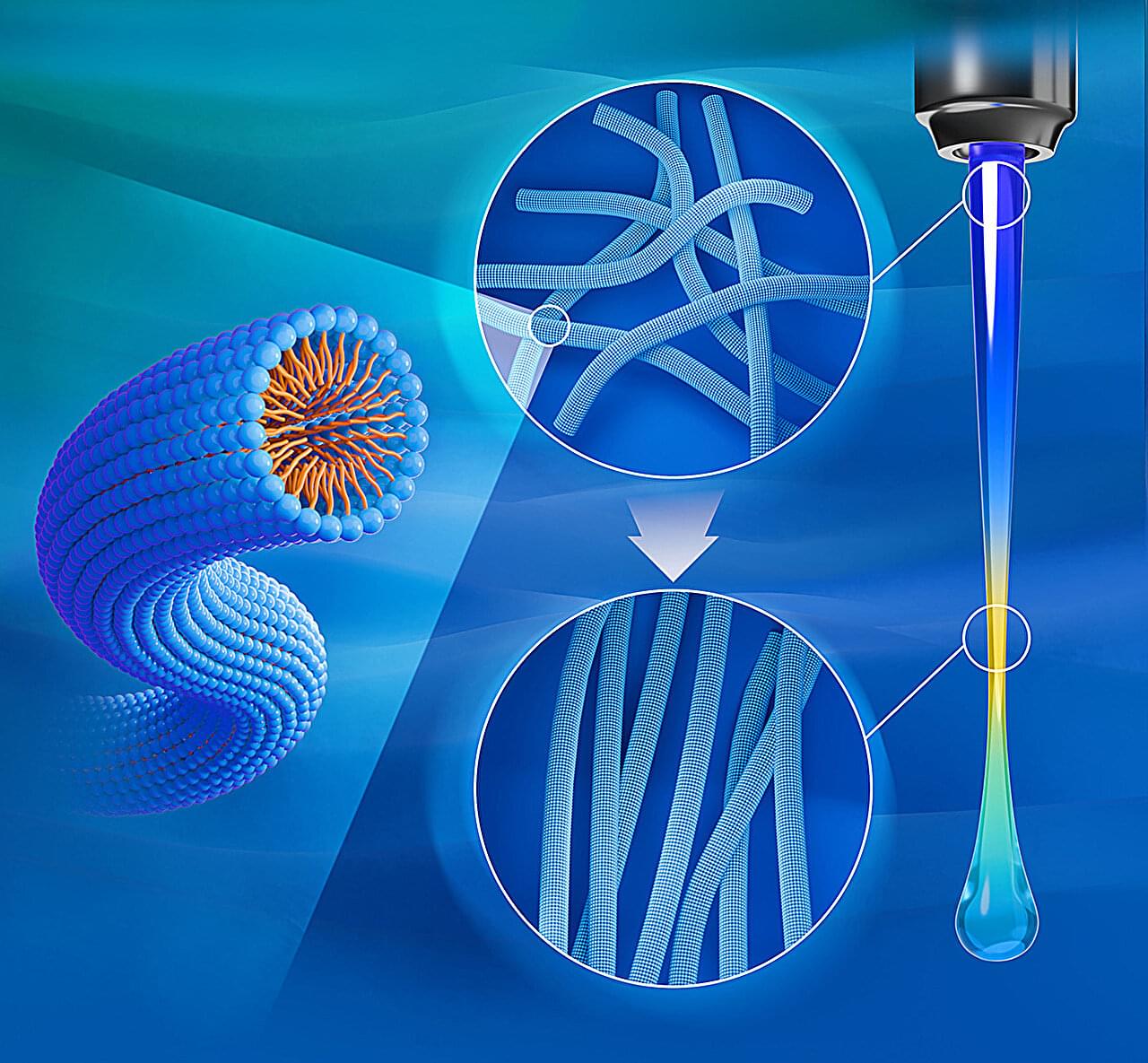

Complex fluids, such as polymer melts and concentrated suspensions, are foundational materials for industrial products, including high-strength plastics and optical components. The final performance of these materials depends on their composition and internal microscopic structure. During manufacturing processes, however, fluids are subjected to mechanical forces that introduce internal stress, leading to microscopic structural damage, which in turn affects the material’s functionality.

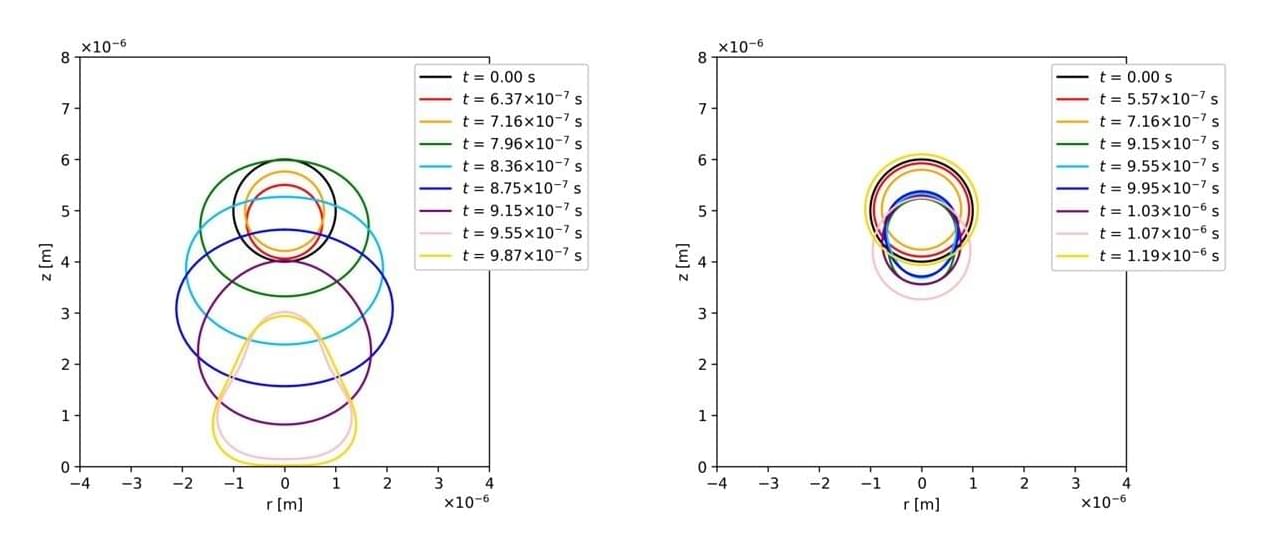

Despite the pressing need to observe and control this structure–stress relationship, few measurement techniques are available for fluids subjected to uniaxially extensional flow. Conventional optical techniques, owing to their low resolution and scope, fail to accurately track changes in the region of maximum stress, making it difficult to link mechanical stresses with observable optical changes.

Addressing this challenge, a research team from Nagoya Institute of Technology (NITech) in Japan, led by Assistant Professor Masakazu Muto recently developed a novel rheo-optical technique that can accurately characterize structural deformations in a complex fluid under extensional flow. Collaborators included Mr. Naoki Kako, Mr. Tatsuya Yoshino, and Professor Shinji Tamano.