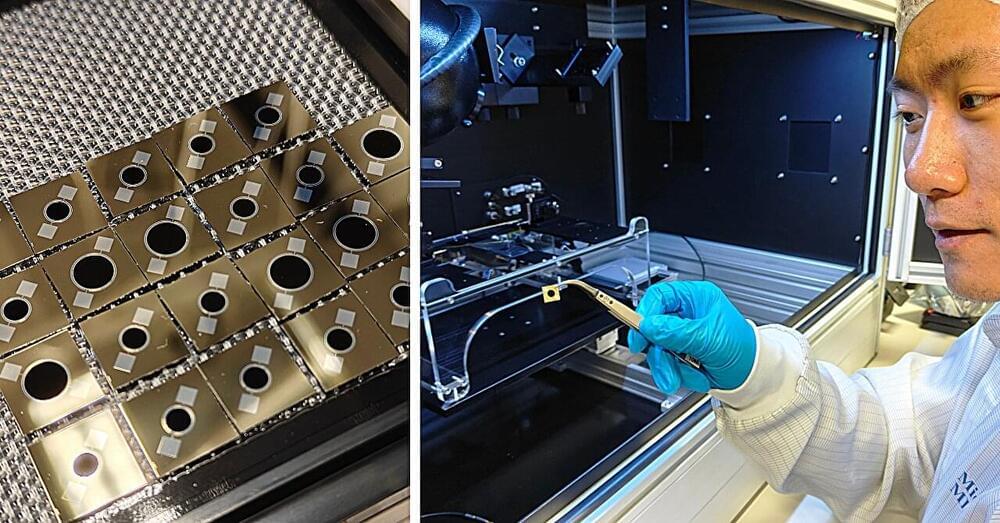

MicroAlgo Inc. has announced the development of a quantum algorithm it claims significantly enhances the efficiency and accuracy of quantum computing operations. According to a company press release, this advance focuses on implementing a FULL adder operation — an essential arithmetic unit — using CPU registers in quantum gate computers.

The company says this achievement could open new pathways for the design and practical application of quantum gate computing systems. However, it’s important to point out that the company did not cite supporting research papers or third-party validations in the announcement.

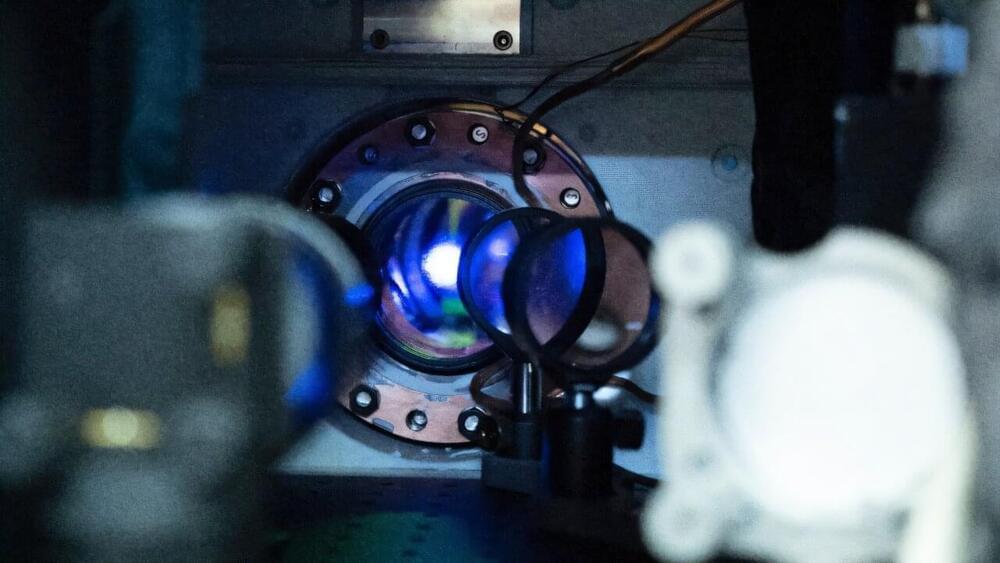

Quantum gate computers operate by applying quantum gates to qubits, which are the basic units of quantum information. Unlike classical bits that represent data as either “0” or “1,” qubits can exist in a superposition of probabilistic states, theoretically enabling quantum systems to process specific tasks more efficiently than classical computers. According to the press release, MicroAlgo’s innovation leverages quantum gates and the properties of qubits, including superposition and entanglement, to simulate and perform FULL adder operations.