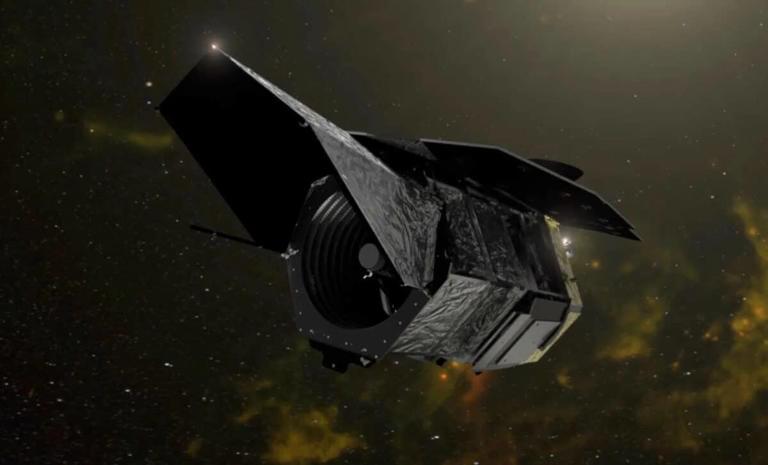

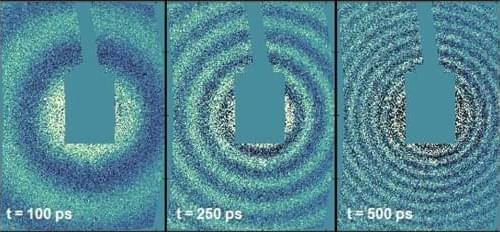

Our universe is filled with galaxies, in all directions as far as our instruments can see. Some researchers estimate that there are as many as 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe. At first glance, these galaxies might appear to be randomly scattered across space, but they’re not. Careful mapping has shown that they are distributed across the surfaces of giant cosmic “bubbles” up to several hundred million light-years across. Inside these bubbles, few galaxies are found, so those regions are called cosmic voids. NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will allow us to measure these voids with new precision, which can tell us about the history of the universe’s expansion.

“Roman’s ability to observe wide areas of the sky to great depths, spotting an abundance of faint and distant galaxies, will revolutionize the study of cosmic voids,” said Giovanni Verza of the Flatiron Institute and New York University, lead author on a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal.

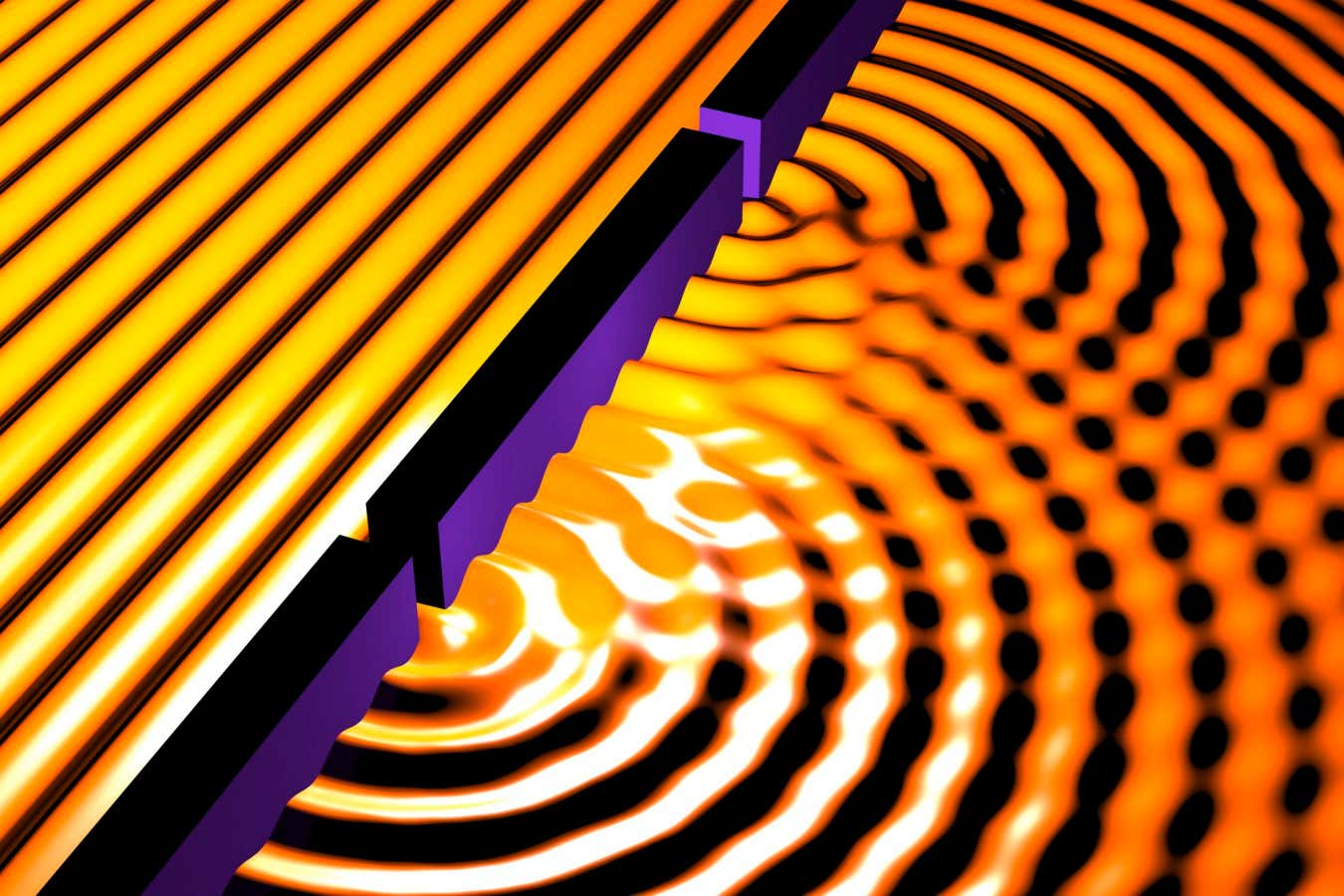

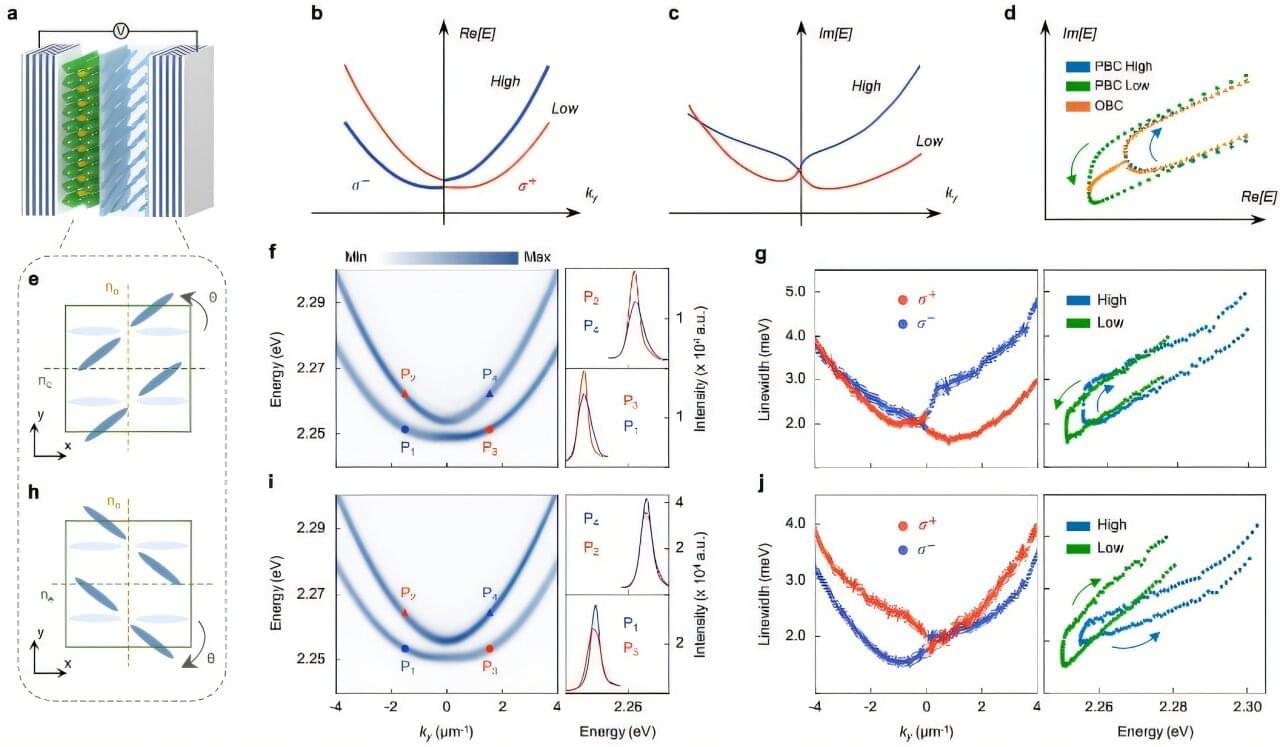

Cosmic recipe The cosmos is made of three key components: normal matter, dark matter, and dark energy. The gravity of normal and dark matter tries to slow the expansion of the universe, while dark energy opposes gravity to speed up the universe’s expansion. The nature of both dark matter and dark energy is currently unknown. Scientists are trying to understand them by studying their effects on things we can observe, such as the distribution of galaxies across space.