Step into the future with “Smart Golden Cities of the Future”, a 1-hour journey exploring how technology and nature will merge to create sustainable, intelligent cities by 2050. In this immersive video, we’ll dive deep into a world where urban spaces are powered by Sci-Fi innovation, green infrastructure, and advanced technologies. From eco-friendly architecture to autonomous transportation systems, discover how the cities of tomorrow will function in harmony with the environment. Imagine a future with clean energy, smart public services, and a thriving connection to nature—where sustainability and futuristic technology drive every aspect of life. Join us for an hour-long exploration of the Smart Cities of 2050, as we uncover the incredible possibilities and challenges of creating urban spaces that work for both people and the planet. ✨ This video was created with passion and love for sharing creative production using AI tools such as: • 🧠 Research: ChatGPT • 🖼️ Image Creation: Leonardo, Midjourney, ImageFX • 🎬 Video Production: Veo 3.1, Runway ML • 🎵 Music Generation: Suno AI • ✂️ Video Editing: CapCut Pro 💡 Note: All of the above AI tools are subscription-based. This project combines imagination and creativity from my perspective as a mechanical engineer who loves exploring the future. 🙏🏻 Please Support: • ✅ Subscribe • 👍 Like • 💬 Comment Thank you so much for watching!I hope you enjoy this journey and gain inspiration from this creative experience ❤️ #SmartCities #Sustainability #FutureOfLiving #SciFiInnovation #EcoFriendlyCities #midjourney #veo3 #sunoai

Category: sustainability – Page 4

OpenAI May Be On The Brink of Collapse

OpenAI is facing a potentially crippling lawsuit from Elon Musk, financial strain, and sustainability concerns, which could lead to its collapse and undermine its mission and trust in its AI technology ## ## Questions to inspire discussion.

Legal and Corporate Structure.

🔴 Q: What equity stake could Musk claim from OpenAI? A: Musk invested $30M representing 60% of OpenAI’s original funding and the lawsuit could force OpenAI to grant him equity as compensation for the nonprofit-to-for-profit transition that allegedly cut him out.

⚖️ Q: What are the trial odds and timeline for Musk’s lawsuit? A: The trial is set for April after a judge rejected OpenAI and Microsoft’s dismissal bid, with Kalshi predicting Musk has a 65% chance of winning the case.

Funding and Financial Stability.

💰 Q: How could the lawsuit impact OpenAI’s ability to raise capital? A: The lawsuit threatens to cut off OpenAI’s lifeline to cash and venture capital funding, potentially leading to insolvency and preventing them from pursuing an IPO due to uncertainty around financial stability and corporate governance.

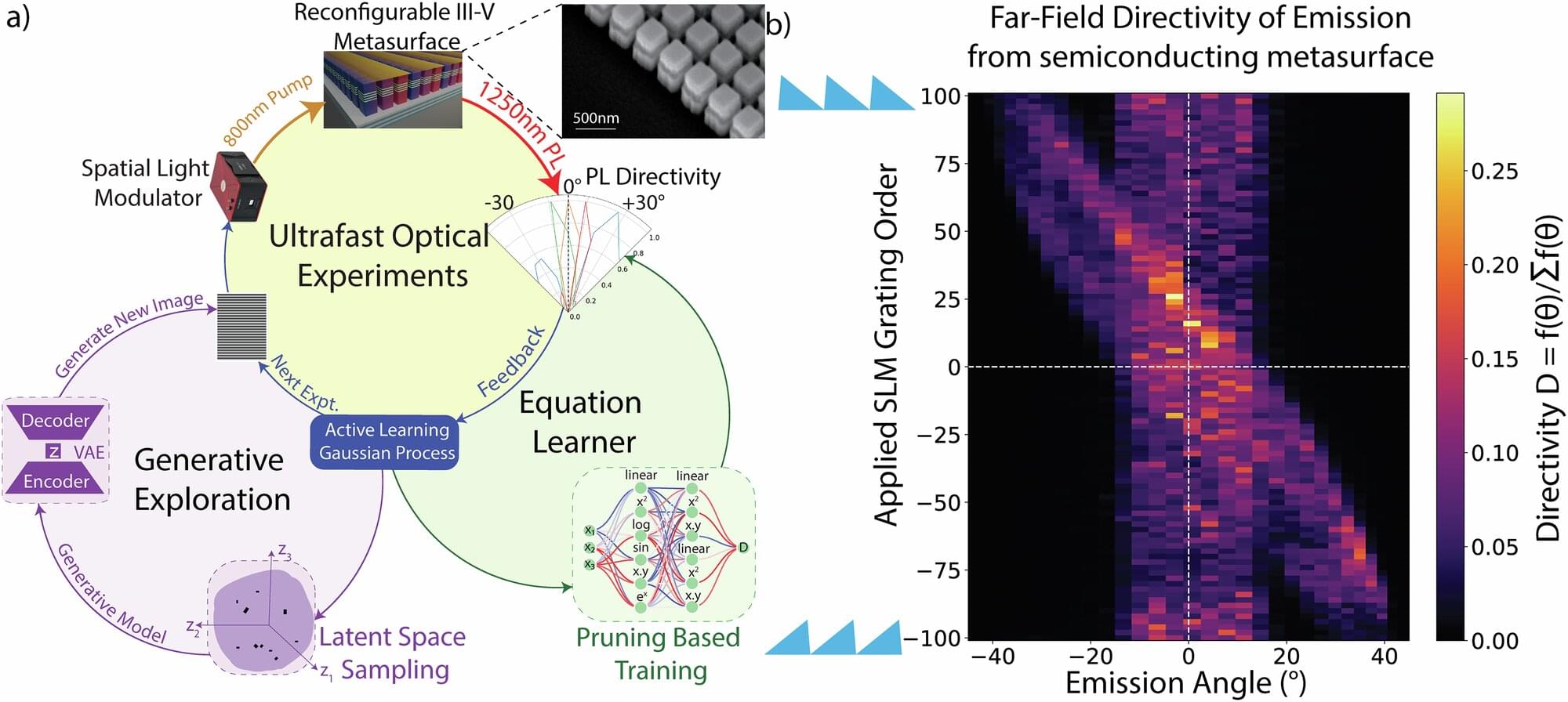

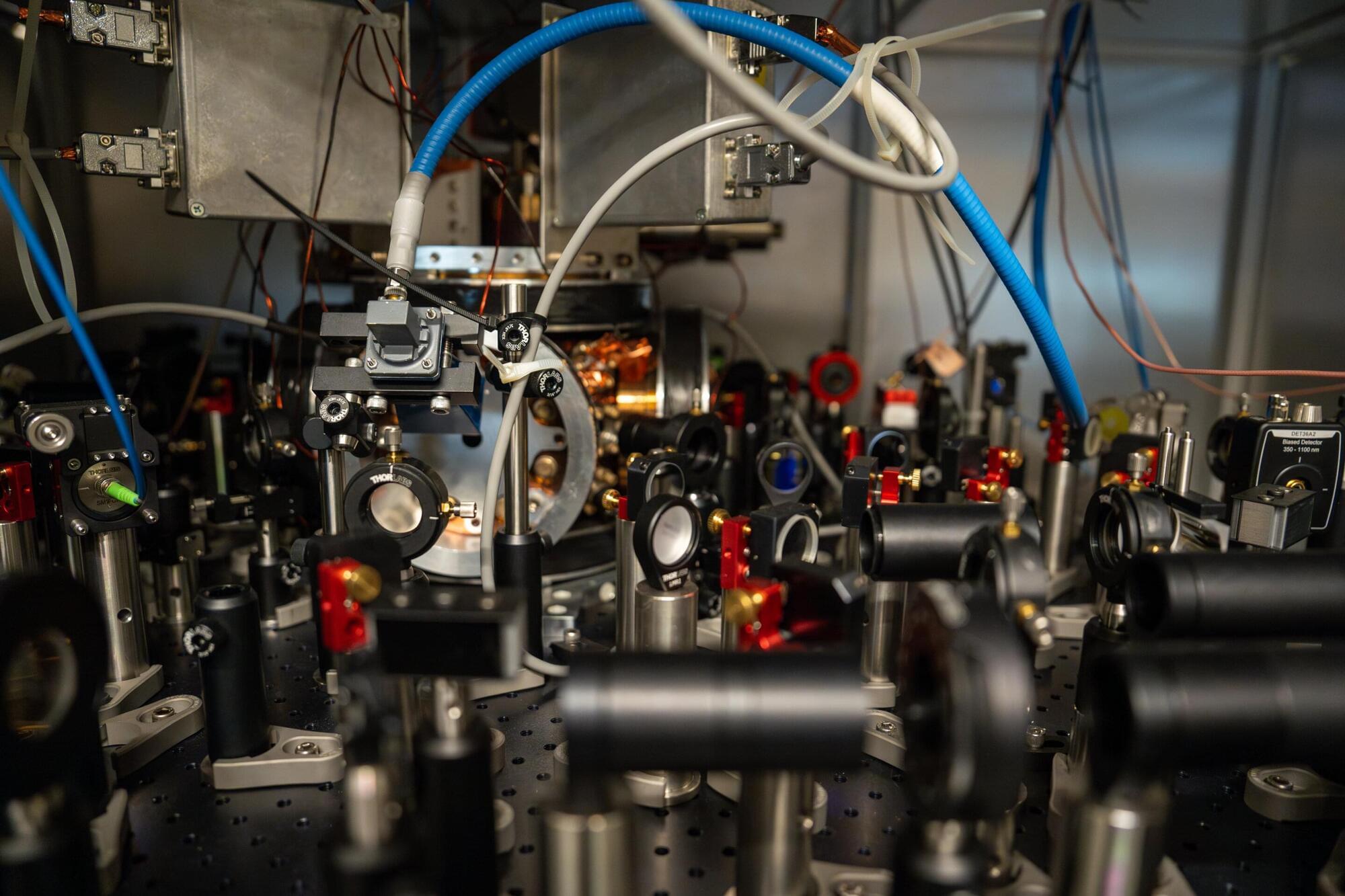

Physicists employ AI labmates to supercharge LED light control

In 2023, a team of physicists from Sandia National Laboratories announced a major discovery: a way to steer LED light. If refined, it could mean someday replacing lasers with cheaper, smaller, more energy-efficient LEDs in countless technologies, from UPC scanners and holographic projectors to self-driving cars. The team assumed it would take years of meticulous experimentation to refine their technique.

Now the same researchers have reported that a trio of artificial intelligence labmates has improved their best results fourfold. It took about five hours.

The resulting paper, now published in Nature Communications, shows how AI is advancing beyond a mere automation tool toward becoming a powerful engine for clear, comprehensible scientific discovery.

Engineering the Future: John Cumbers on Synthetic Biology and Sustainability

Please Like 👍 + Share ⭐ + Subscribe ✅

In this episode of the New Earth Entrepreneurs podcast, we sit down with John Cumbers, founder of SynBioBeta, to discuss how synthetic biology is reshaping industries and creating sustainable solutions.

John shares insights into the role of bio-manufacturing in decarbonizing supply chains, government initiatives supporting bio-innovation, and the potential for space applications of synthetic biology.

Learn how SynBioBeta is building a passionate community of changemakers to engineer a better, more sustainable world.

Learn more about SynBioBeta and their upcoming events at: www.synbiobeta.com.

Connect with John on LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/john-cumbers-542220

The New Earth Entrepreneurs Podcast explores social entrepreneurship and corporate sustainability through engaging conversations with visionary leaders.

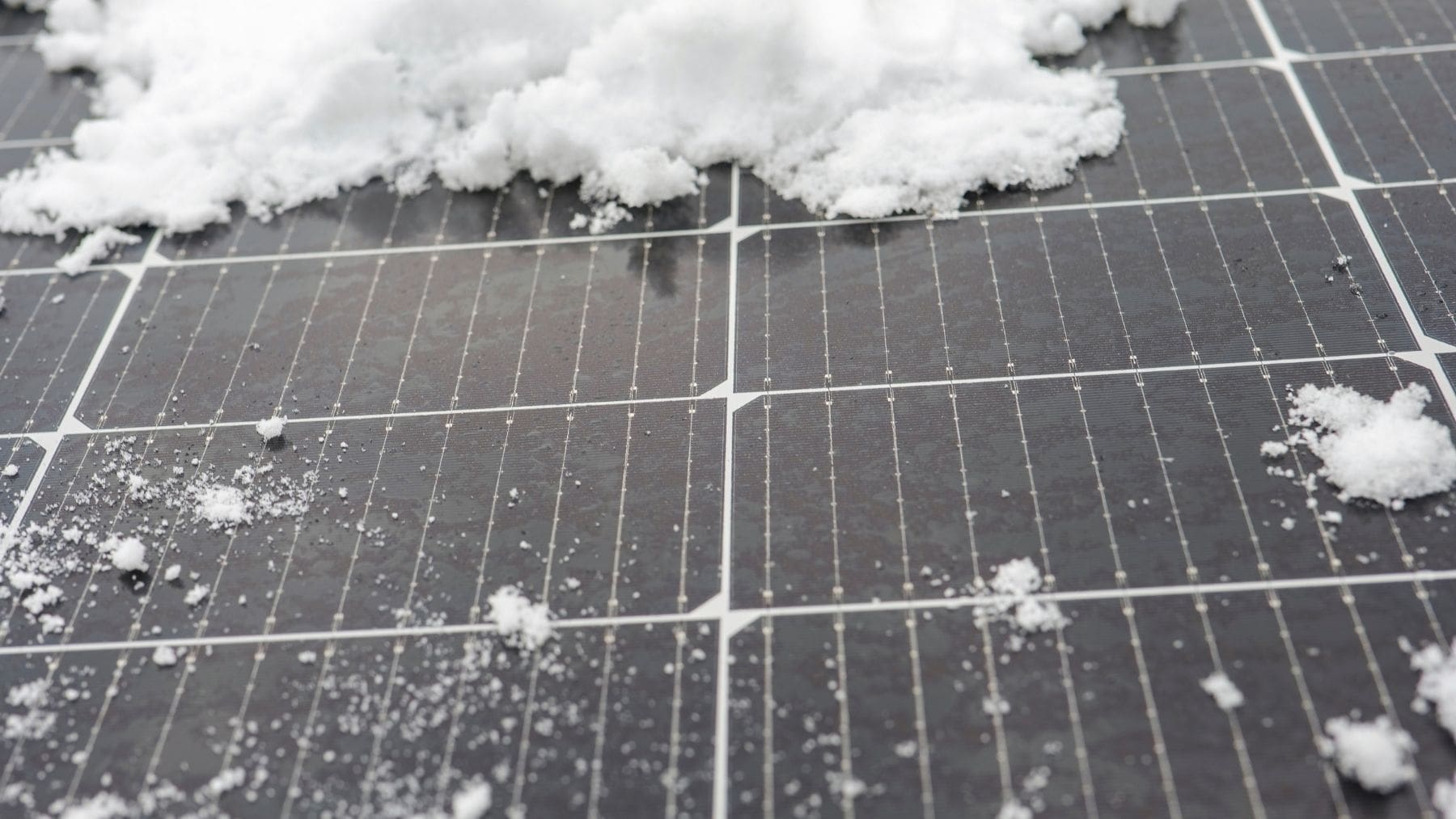

Forget solar panels in summer: Here’s why winter Is the best time to switch your home to solar

Regardless of which U.S. state you live in, we can all agree that electricity in the U.S. is quite expensive. Of course, prices may vary depending on where you live, but in general, investing in clean energy has never been more desirable than it is now. But with so many options to choose from, when are solar panels, for example, your best option? Well, if you live in a region with colder weather, your best option may be to invest in solar energy, as a PV expert believes that solar panels are more efficient in cold weather.

Investing in clean energy: Your options

The majority of Americans most likely got quite the fright when they opened their last utility bill, and things may not look up just yet this month. Beyond the fact that one’s heating and thus electricity bill skyrockets during the winter due to increased usage, other factors also play a significant role in driving up electricity prices.

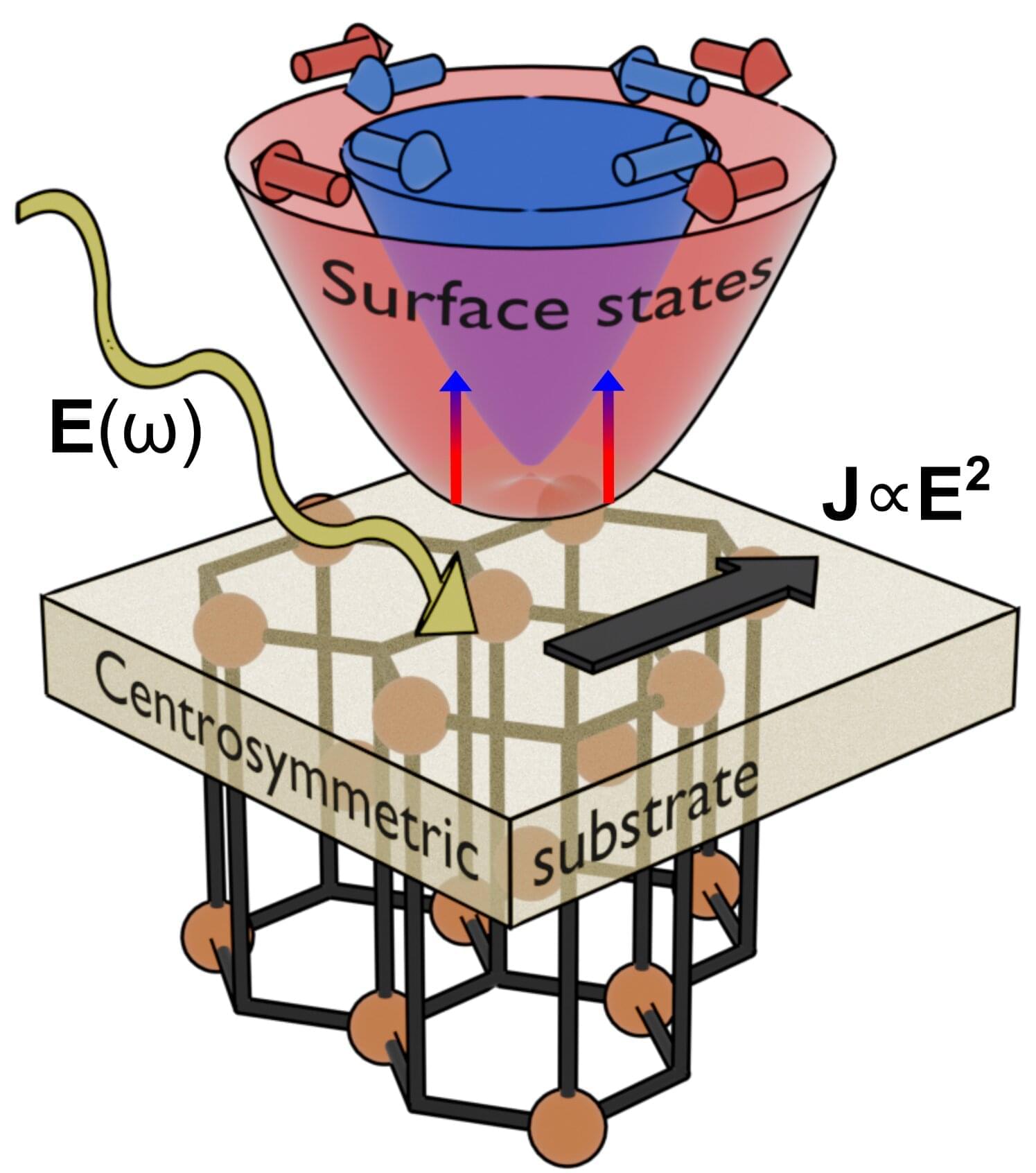

Overcoming symmetry limits in photovoltaics through surface engineering

A recent study carried out by researchers from EHU, the Materials Physics Center, nanoGUNE, and DIPC introduces a novel approach to solar energy conversion and spintronics. The work tackles a long-standing limitation in the bulk photovoltaic effect—the need for non-centrosymmetric crystals—by demonstrating that even perfectly symmetric materials can generate significant photocurrents through engineered surface electronic states. This discovery opens new pathways for designing efficient light-to-electricity conversion systems and ultrafast spintronic devices.

The work is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Conventional solar cells rely on carefully engineered interfaces, such as p–n junctions, to turn light into electricity. A more exotic mechanism—the bulk photovoltaic effect —can generate electrical current directly in a material without such junctions, but only if its crystal structure lacks inversion symmetry. This strict requirement has long restricted the search for practical materials.

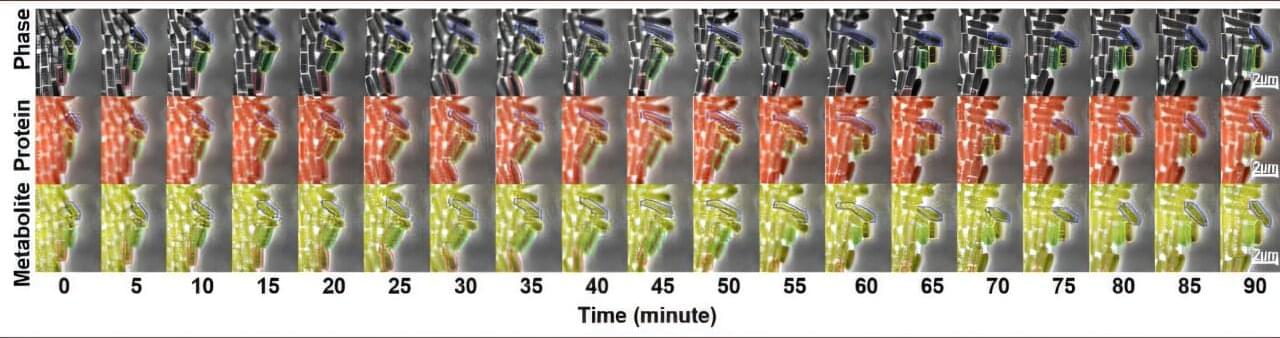

Exploring metabolic noise opens new paths to better biomanufacturing

Much like humans, microbial organisms can be fickle in their productivity. One moment they’re cranking out useful chemicals in vast fermentation tanks, metabolizing feed to make products from pharmaceuticals and supplements to biodegradable plastics or fuels, and the next, they inexplicably go on strike.

Engineers at Washington University in St. Louis have found the source of the fluctuating metabolic activity in microorganisms and developed tools to keep every microbial cell at peak productivity during biomanufacturing.

The work, published in Nature Communications, tracks hundreds of E. coli cells as they produce a yellow food pigment—betaxanthin—while growing, dividing and carrying out normal metabolic activities.

The ocean absorbed a stunning amount of heat in 2025

Earth’s oceans reached their highest heat levels on record in 2025, absorbing vast amounts of excess energy from the atmosphere. This steady buildup has accelerated since the 1990s and is now driving stronger storms, heavier rainfall, and rising sea levels. While surface temperatures fluctuate year to year, the ocean’s long-term warming trend shows no sign of slowing.

EXLUMINA Founder: SpaceX Already Controls the Future of Space AI

SpaceX is well-positioned to dominate the future of space AI due to its innovative technologies, scalable satellite production, and strategic partnerships, which will enable it to efficiently deploy and operate a massive network of satellites with advanced computing capabilities ## ## Questions to inspire discussion.

Launch Economics & Infrastructure.

🚀 Q: Why is Starship essential for space AI data centers? A: Starship enables 100-1000x more satellites than Falcon 9, making orbital AI economically viable through massive scaling and lower launch costs, while Falcon 9 remains too expensive for commercial viability at scale.

🛰️ Q: What is SpaceX’s deployment plan for AI satellites? A: SpaceX plans Starlink version 3 satellites with 100 Nvidia chips each, deploying 5,000 satellites via 100 Starship launches at 50 satellites per flight to create a gigawatt-scale AI constellation by early 2030s.

📈 Q: What launch cadence gives SpaceX its advantage? A: SpaceX plans 10,000 annual launches and produces satellites at 10-100x the level of competitors, creating a monopoly on launch and manufacturing that positions them as the gatekeeper to space AI success.

Energy & Power Systems.

Quantum simulator reveals how vibrations steer energy flow in molecules

Researchers led by Rice University’s Guido Pagano used a specialized quantum device to simulate a vibrating molecule and track how energy moves within it. The work, published Dec. 5 in Nature Communications, could improve understanding of basic mechanisms behind phenomena such as photosynthesis and solar energy conversion.

The researchers modeled a simple two-site molecule with one part supplying energy and the other receiving it, both shaped by vibrations and their environment. By tuning the system, they could directly observe energy moving from donor to acceptor and study how vibrations and energy loss influence that transfer, providing a controlled way to test theories of energy flow in complex materials.

“We can now observe how energy moves in a synthetic molecule while independently adjusting each variable to see what truly matters,” said Pagano, assistant professor of physics and astronomy.