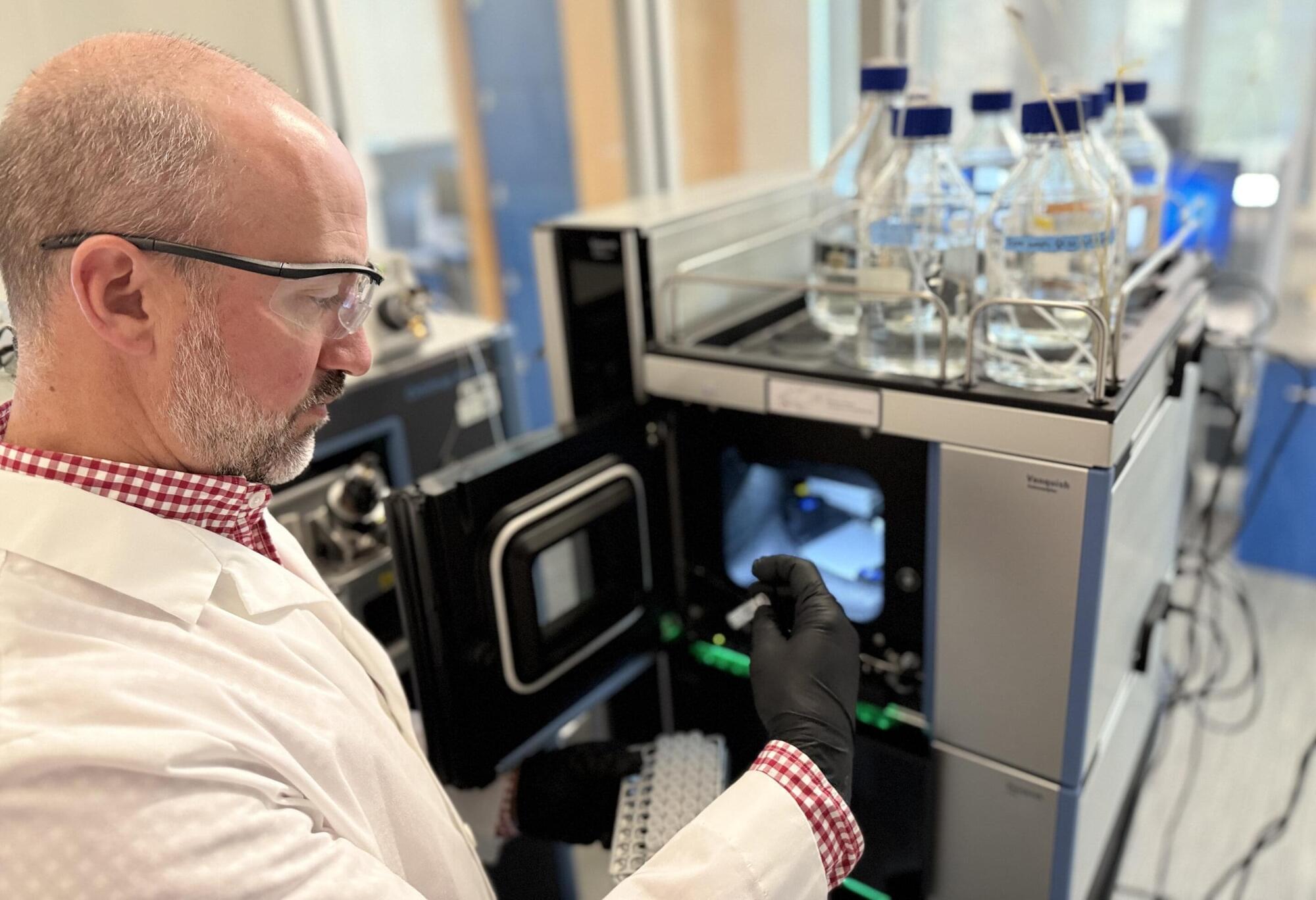

Chinese scientists claim to have reported a major jump in capacitor manufacturing earlier this month. The group has cut the production time for dielectric energy storage parts to one second.

The announcement has drawn widespread attention because it points to fast, stable energy storage for advanced defense systems and electric vehicles.

The team used a flash annealing method that heats and cools material at a rate of about 1,832°F (1,000°C) per second. This speed allows crystal films to form on a silicon wafer in a single step. Other techniques require far more time and can take from 3 minutes to 1 hour, depending on the film quality.