Amidst Washington’s escalating tech sanctions, Chinese researchers find a new way to enhance GPU efficiency from the software end.

Category: supercomputing – Page 22

AI program plays the long game to solve decades-old math problems

A game of chess requires its players to think several moves ahead, a skill that computer programs have mastered over the years. Back in 1996, an IBM supercomputer famously beat the then world chess champion Garry Kasparov. Later, in 2017, an artificial intelligence (AI) program developed by Google DeepMind, called AlphaZero, triumphed over the best computerized chess engines of the time after training itself to play the game in a matter of hours.

More recently, some mathematicians have begun to actively pursue the question of whether AI programs can also help in cracking some of the world’s toughest math problems. But, whereas an average game of chess lasts about 30 to 40 moves, these research-level math problems require solutions that take a million or more steps, or moves.

In a paper appearing on the arXiv preprint server, a team led by Caltech’s Sergei Gukov, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Theoretical Physics and Mathematics, describes developing a new type of machine-learning algorithm that can solve math problems requiring extremely long sequences of steps. The team used their new algorithm to solve families of problems related to an overarching decades-old math problem called the Andrews–Curtis conjecture. In essence, the algorithm can think farther ahead than even advanced programs like AlphaZero.

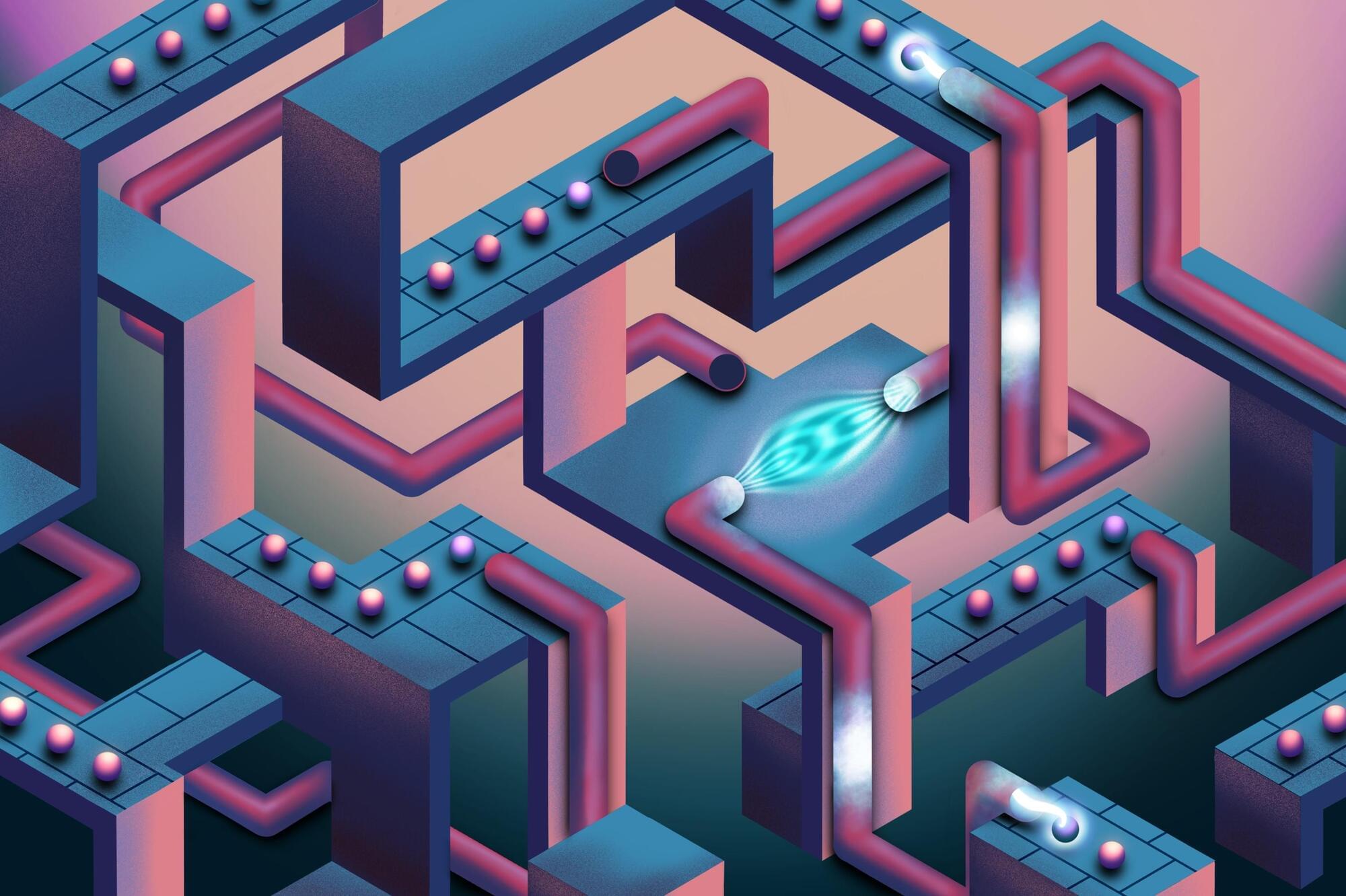

First distributed quantum algorithm brings quantum supercomputers closer

In a milestone that brings quantum computing tangibly closer to large-scale practical use, scientists at Oxford University’s Department of Physics have demonstrated the first instance of distributed quantum computing. Using a photonic network interface, they successfully linked two separate quantum processors to form a single, fully connected quantum computer, paving the way to tackling computational challenges previously out of reach. The results have been published in Nature.

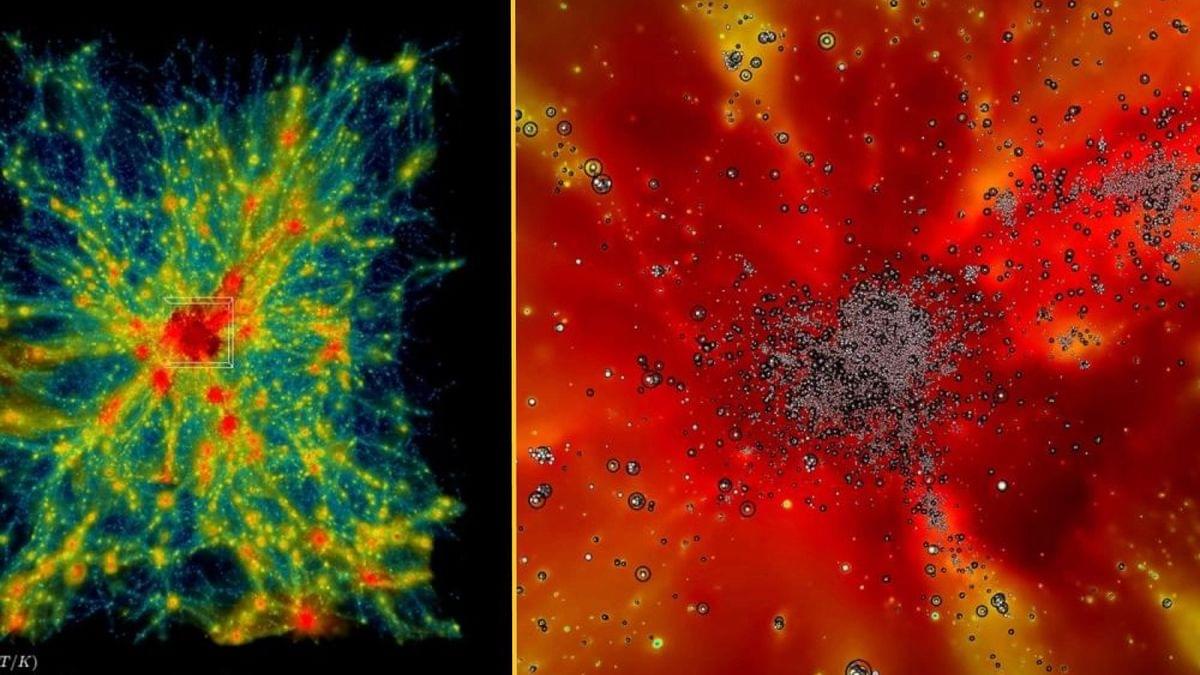

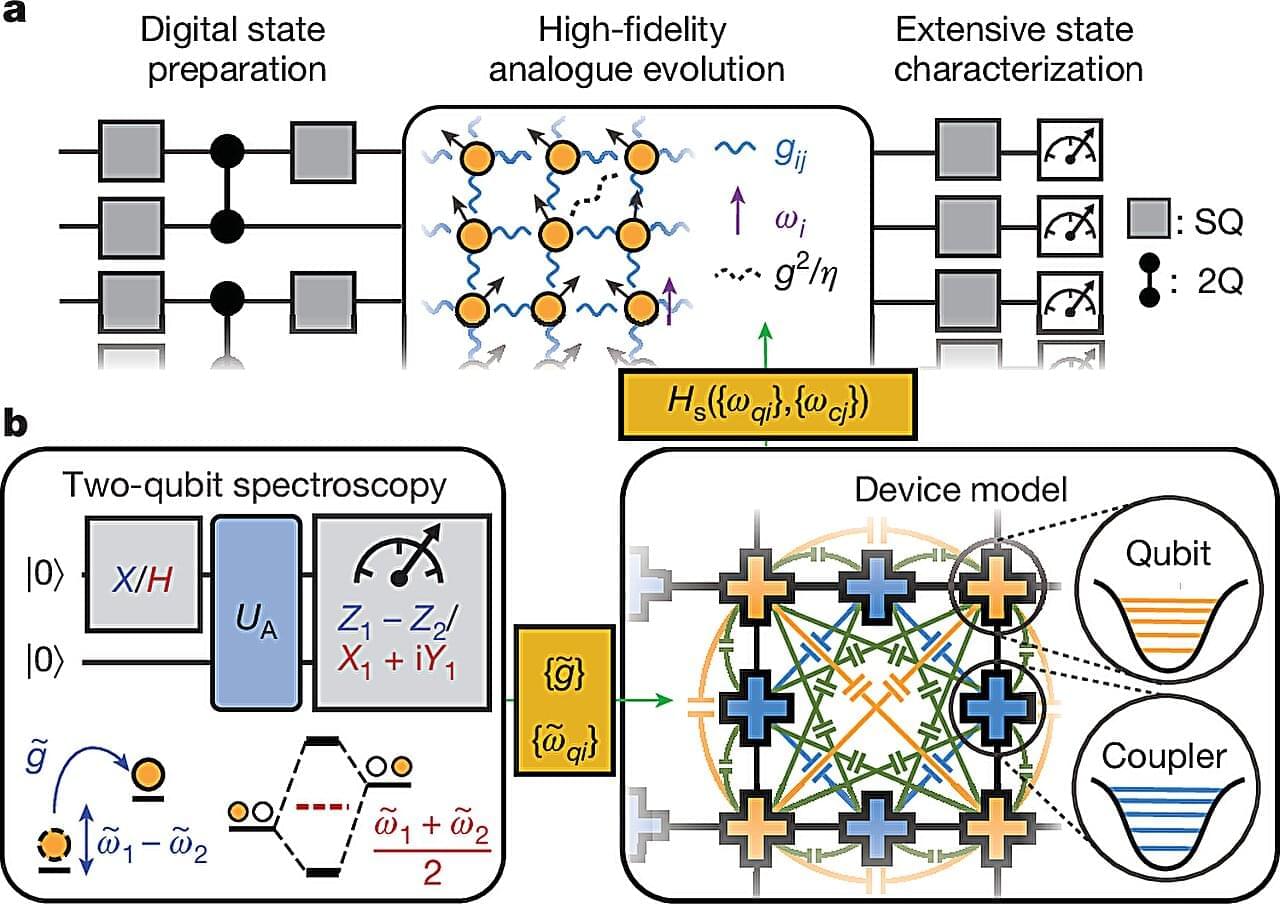

Quantum simulator combines digital and analog modes to calculate physical processes with unprecedented precision

How does cold milk disperse when it is dripped into hot coffee? Even the fastest supercomputers are unable to perform the necessary calculations with high precision because the underlying quantum physical processes are extremely complex.

In 1982, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman suggested that, instead of using conventional computers, such questions are better solved using a quantum computer, which can simulate the quantum physical processes efficiently—a quantum simulator. With the rapid progress now being made in the development of quantum computers, Feynman’s vision could soon become a reality.

Together with researchers from Google and universities in five countries, Andreas Läuchli and Andreas Elben, two theoretical physicists at PSI, have built and successfully tested a new type of digital–analog quantum simulator.

Supercomputer Aurora is now available for all researchers

Aurora, the exascale supercomputer at Argonne National Laboratory, is now available to researchers worldwide, as announced by the system’s operators from the U.S. Department of Energy on January 28, 2025. One of the goals for Aurora is to train large language models for science.

According to official reports, among the world’s fastest supercomputers, there are currently only three systems that reach at least one exaflop. An exaflop is a quintillion (10¹⁸) calculations per second—that’s like a regular calculator computing continuously for 31 billion years, but completing everything in just a single second. Or, to put it briefly: exaflop supercomputers are incredibly fast.

The fastest among the swift three is El Capitan at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory with 1.742 exaflops per second under the HPL benchmark (High-Performance Linpack, a standardized test for measuring the computing power of supercomputers). It is followed by Frontier with 1.353 exaflops/s at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The trio is completed by Aurora with 1.012 exaflops/s. Incidentally, all three laboratories belong to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

Online Seminar: How to Build a Quantum Supercomputer — Scaling Challenges and Opportunities

Quantum computing represents a paradigm shift in computation with the potential to revolutionize scientific discovery and technological innovation. This seminar will examine the roadmap for constructing quantum supercomputers, emphasizing the integration of quantum processors with traditional high-performance computing (HPC) systems. The seminar will be led by prominent experts Prof. John Martinis (Qolab), Dr. Masoud Mohseni (HPE), and Dr. Yonatan Cohen (Quantum Machines), who will discuss the critical hurdles and opportunities in scaling quantum computing, drawing upon their latest research publication, “How to Build a Quantum Supercomputer: Scaling Challenges and Opportunities”