O,.o.

Livescience.com | By LIVESCIENCE

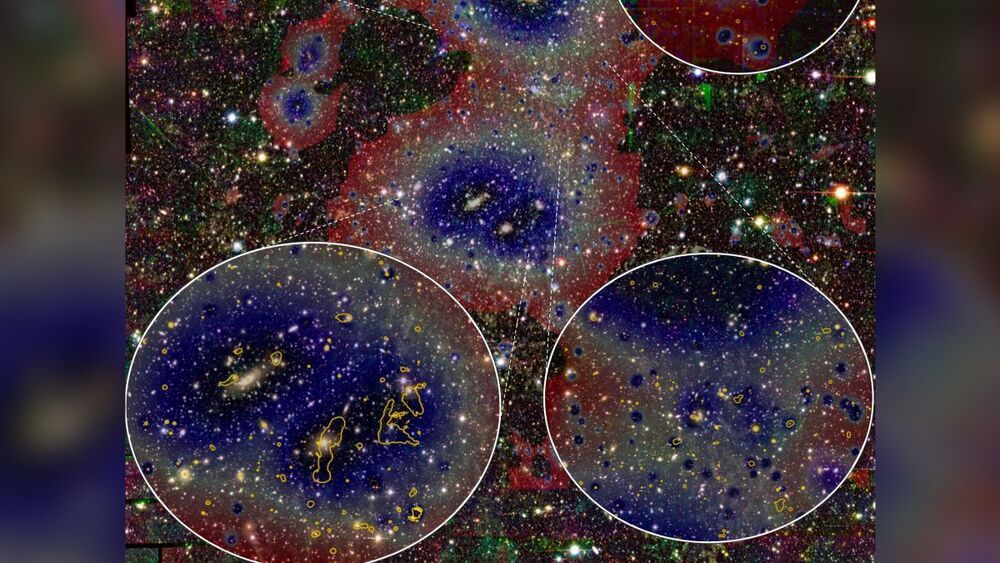

Astronomers discover one of the longest filaments of the cosmic web. And it may help solve the puzzle of the universe’s missing matter.

O,.o.

Livescience.com | By LIVESCIENCE

Astronomers discover one of the longest filaments of the cosmic web. And it may help solve the puzzle of the universe’s missing matter.

Members of the US Space Force will be known as “guardians”, it was announced on the military service’s first birthday.

US Vice President Mike Pence said: It is my honour, on behalf of the president of the United States, to announce that henceforth the men and women of the United States Space Force will be known as guardians.

Mike Pence says soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines and guardians will be defending our nation for generations to come.

If you thought you knew all of the mid-drive motors in the e-bike world, think again. The French company Valeo has just unveiled a radical new type of mid-drive electric motor that adds a built-in automatic transmission.

Automatic transmissions alone aren’t unique in the e-bike space.

We’ve tested several models that feature mid-drive motors paired with automatic transmissions.

MANILA, Philippines — A Filipino startup is recognized globally in developing a dengue hotspot prediction system using satellite and climate data in the 2020 Group on Earth Observations Sustainable Development Goals (GEO SDG) Awards for the Sectoral category, For-Profit. The GEO SDG Awards recognize the productivity, ingenuity, proficiency, novelty, and exemplary communications of results and experiences in the use of Earth observations to support sustainable development.

CirroLytix Research Services was formed to create social impact through big data. Through the application of machine learning, data engineering, remote sensing, and social listening, the Philippines-based data analytics firm hopes to help governments, researchers, non-government organizations (NGO), and social enterprises achieve positive change. The Advanced Early Dengue Prediction and Exploration Service (Project AEDES) is one of the CirroLytix’s flagship projects developed during the 2019 National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) International Space Apps Challenge. It combines digital, climate, and remote sensing to nowcast dengue trends and detect mosquito habitats to help pre-empt cases of dengue. Project AEDES process leverages normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), Fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (FAPAR), and normalized difference water index (NDWI) readings from Landsat and Sentinel-2 to estimate still water areas on the ground, which is correlated with dengue case counts from national health centers.

Dominic Vincent “Doc” Ligot, co-founder and chief technology officer of CirroLytix, describes Project AEDES as an “early detection of panics from online searches, anticipating case counts from environment readings, but most importantly pinpointing hotspots from mosquito habitat detection.”

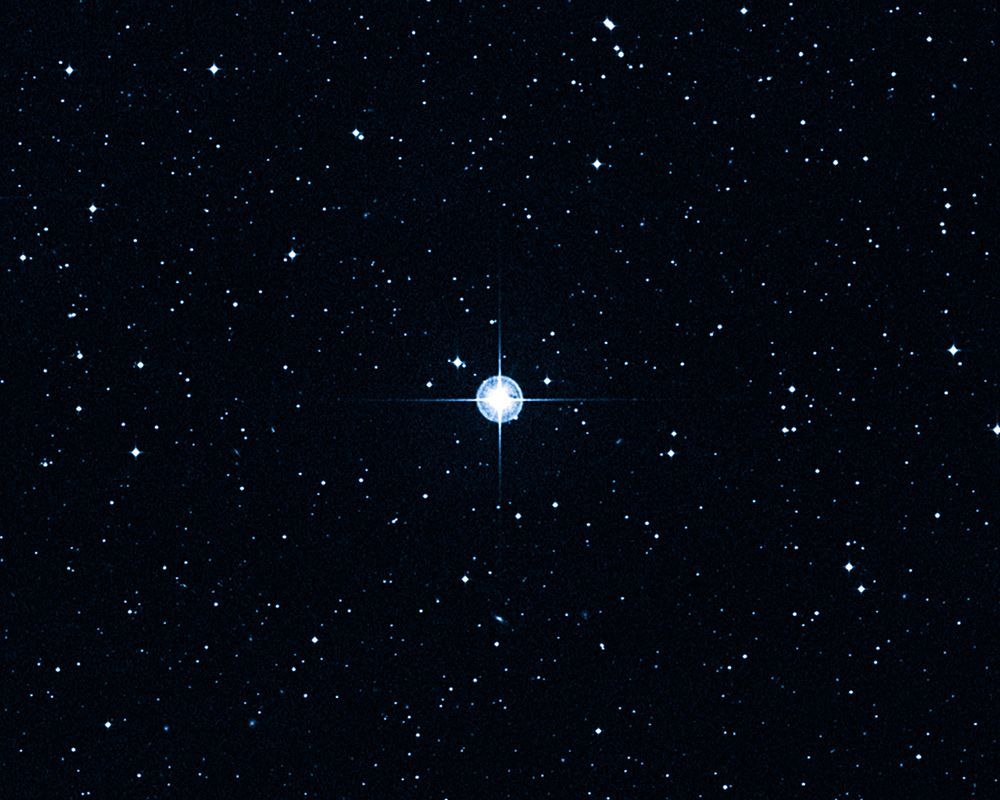

On Dec. 21, humans can witness something not seen in nearly 800 years.

That’s right, during the upcoming winter solstice, Jupiter and Saturn will line up to create what is known as the “Christmas Star” or “Star of Bethlehem.”

These two planets haven’t appeared this (relatively) close together from Earth’s vantage point since the Middle Ages.

Social media was abuzz Sunday after reports that an object emitting an intense light had been spotted falling from the skies above Japan in the early hours of the morning.

Supplied photo taken from video footage of a fireball seen in Gifu Prefecture, central Japan. (Kyodo)

The fireball, believed to be a bolide — a type of shooting star often compared to a full moon for its brightness — could be seen clearly from parts of western and central Japan.

A trio of researchers at Johannes Kepler University has used artificial intelligence to improve thermal imaging camera searches of people lost in the woods. In their paper published in the journal Nature Machine Intelligence, David Schedl, Indrajit Kurmi and Oliver Bimber, describe how they applied a deep learning network to the problem of people lost in the woods and how well it worked.

When people become lost in forests, search and rescue experts use helicopters to fly over the area where they are most likely to be found. In addition to simply scanning the ground below, the researchers use binoculars and thermal imaging cameras. It is hoped that such cameras will highlight differences in body temperature of people on the ground versus their surroundings making them easier to spot. Unfortunately, in some instances thermal imaging does not work as intended because of vegetation covering subsoil or the sun heating the trees to a temperature that is similar to the body temperature of the person that is lost. In this new effort, the researchers sought to overcome these problems by using a deep learning application to improve the images that are made.

The solution the team developed involved using an AI application to process multiple images of a given area. They compare it to using AI to process data from multiple radio telescopes. Doing so allows several telescopes to operate as a single large telescope. In like manner, the AI application they used allowed multiple thermal images taken from a helicopter (or drone) to create an image as if it were captured by a camera with a much larger lens. After processing, the images that were produced had a much higher depth of field—in them the tops of the trees appeared blurred while people on the ground became much more recognizable. To train the AI system, the researchers had to create their own database of images. They used drones to take pictures of volunteers on the ground in a wide variety of positions.

Space Force members will be known as “Guardians” from now on, Vice President Michael R. Pence announced Dec. 18.

“Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, Marines, and Guardians will be defending our nation for generations to come,” he said at a Dec. 18 White House ceremony celebrating the Space Force’s upcoming birthday.

As the Space Force turns 1 year old on Dec. 20, abandoning the moniker of “Airman” is one of the most prominent moves made so far to distinguish space personnel from the Air Force they came from. An effort to crowdsource options brought in more than 500 responses earlier this year, including “sentinel” and “vanguard.”

Popular media and policy-oriented discussions on the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) into nuclear weapons systems frequently focus on matters of launch authority—that is, whether AI, especially machine learning (ML) capabilities, should be incorporated into the decision to use nuclear weapons and thereby reduce the role of human control in the decisionmaking process. This is a future we should avoid. Yet while the extreme case of automating nuclear weapons use is high stakes, and thus existential to get right, there are many other areas of potential AI adoption into the nuclear enterprise that require assessment. Moreover, as the conventional military moves rapidly to adopt AI tools in a host of mission areas, the overlapping consequences for the nuclear mission space, including in nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3), may be underappreciated.

AI may be used in ways that do not directly involve or are not immediately recognizable to senior decisionmakers. These areas of AI application are far left of an operational decision or decision to launch and include four priority sectors: security and defense; intelligence activities and indications and warning; modeling and simulation, optimization, and data analytics; and logistics and maintenance. Given the rapid pace of development, even if algorithms are not used to launch nuclear weapons, ML could shape the design of the next-generation ballistic missile or be embedded in the underlying logistics infrastructure. ML vision models may undergird the intelligence process that detects the movement of adversary mobile missile launchers and optimize the tipping and queuing of overhead surveillance assets, even as a human decisionmaker remains firmly in the loop in any ultimate decisions about nuclear use. Understanding and navigating these developments in the context of nuclear deterrence and the understanding of escalation risks will require the analytical attention of the nuclear community and likely the adoption of risk management approaches, especially where the exclusion of AI is not reasonable or feasible.