They’re calling it an “apogee kick motor,” but the object’s true identity and purpose remain unknown.

Category: space – Page 641

101 Gigawatt Hours of Solar Power From Noise Barriers Possible

The noise barriers built in Switzerland can supply up to 101 gigawatt hours of solar electricity every year. The prerequisite is that all noise barriers are covered with solar installations, as far as this is possible and economical. This would be possible with a solar capacity of 111 megawatts. This is the result of a study commissioned by the Swiss Federal Council at the instigation of Bruno Storni, a member of parliament from the Swiss Social Democratic Party.

This potential is far below what is technically feasible. However, the authors of the study subtracted the potential that would hardly be economically feasible according to the current state of the art. In addition, they had to take into account site conditions such as shading of the walls or safety aspects.

101 gigawatt hours sounds a lot. But this is only 0.15 per cent of the usable solar potential on roofs and facades used for comparison in Switzerland. For the federal road administration Astra and the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB), however, it is nevertheless a major step towards climate neutrality. After all, solar installations on noise barriers near road tunnels alone cover eleven per cent of the potential on Astra’s total surfaces.

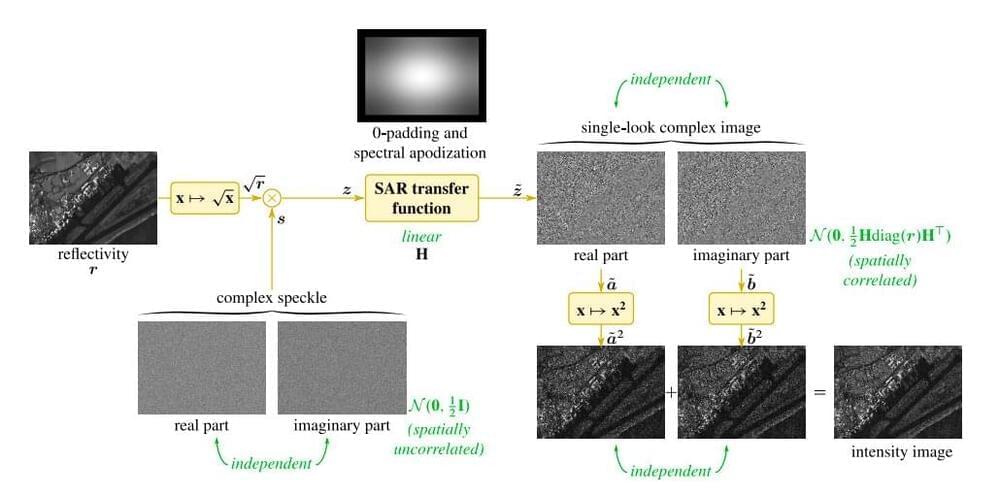

MERLIN: A self-supervised strategy to train deep despeckling networks

When a highly coherent light beam, such as that emitted by radars, is diffusely reflected on a surface with a rough structure (e.g., a piece of paper, white paint or a metallic surface), it produces a random granular effect known as the ‘speckle’ pattern. This effect results in strong fluctuations that can reduce the quality and interpretability of images collected by synthetic aperture radar (SAR) techniques.

SAR is an imaging method that can produce fine-resolution 2D or 3D images using a resolution-limited radar system. It is often employed to collect images of landscapes or object reconstructions, which can be used to create millimeter-to-centimeter scale models of the surface of Earth or other planets.

To improve the quality and reliability of SAR data, researchers worldwide have been trying to develop techniques based on deep neural networks that could reduce the speckle effect. While some of these techniques have achieved promising results, their performance is still not optimal.

NASA solar probe bombarded

The Parker Solar Probe is an engineering marvel, designed by NASA to “touch the sun” and reveal some of the star’s most closely guarded secrets. The scorch-proof craft, launched by NASA in August 2,018 has been slowly sidling up to our solar system’s blazing inferno for the past three years, studying its magnetic fields and particle physics along the way. It’s been a successful journey, and the probe has been racking up speed records. In 2,020 it became the fastest human-made object ever built.

But Parker is learning a lesson about the consequences of its great speed: constant bombardment by space dust.

Unlock the biggest mysteries of our planet and beyond with the CNET Science newsletter. Delivered Mondays.

What If You Traveled One Billion Years Into the Future?

If you traveled 10,000 years into the future, what would planet Earth look like? Would most of its surface be covered in volcanoes? Or would it be frozen in ice? What if you traveled even further, to one million years in the future? Would all of the oceans have evaporated? Or would it have become one giant water world? Now, what about one billion years? Would there be any humans left? Or would they have settled in other parts of the galaxy?

Transcript and sources: https://whatifshow.com/what-if-you-traveled-one-billion-years-into-the-future/

Join this channel to get access to perks:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCphTF9wHwhCt-BzIq-s4V-g/join.

Watch more what-if scenarios:

Planet Earth: http://bit.ly/YT-what-if-Earth.

The Cosmos: http://bit.ly/YT-what-if-Cosmos.

Technology: http://bit.ly/YT-what-if-Technology.

Your Body: http://bit.ly/YT-what-if-Body.

Humanity: http://bit.ly/YT-what-if-Humanity.

T-shirts and merch: http://bit.ly/whatifstore.

Suggest an episode: http://bit.ly/suggest-whatif.

Newsletter: http://bit.ly/whatif-newsletter.

Feedback and inquiries: https://underknown.com/contact/

Mansoor Hanif — Executive Director, Emerging Technologies, NEOM — An Accelerator Of Human Progress

A US$500 billion accelerator of human progress — mansoor hanif, executive director, emerging technologies, NEOM.

Mansoor Hanif is the Executive Director of Emerging Technologies at NEOM (https://www.neom.com/en-us), a fascinating $500 billion planned cognitive city” & tourist destination, located in north west Saudi Arabia, where he is responsible for all R&D activities for the Technology & Digital sector, including space technologies, advanced robotics, human-machine interfaces, sustainable infrastructure, digital master plans, digital experience platforms and mixed reality. He also leads NEOM’s collaborative research activities with local and global universities and research institutions, as well as manages the team developing world-leading Regulations for Communications and Connectivity.

Prior to this role, Mr Hanif served as Executive Director, Technology & Digital Infrastructure, where he oversaw the design and implementation of NEOM’s fixed, mobile, satellite and sub-sea networks.

An industry leader, Mr Hanif has over 25 years of experience in planning, building, optimizing and operating mobile networks around the world. He is patron of the Institute of Telecommunications Professionals (ITP), a member of the Steering Board of the UK5G Innovation Network, and on the Advisory Boards of the Satellite Applications Catapult and University College London (UCL) Electrical and Electronic Engineering Dept.

Prior to joining NEOM, Mr Hanif was Chief Technology Officer of Ofcom, the UK telecoms and media regulator, where he oversaw the security and resilience of the nation’s networks.

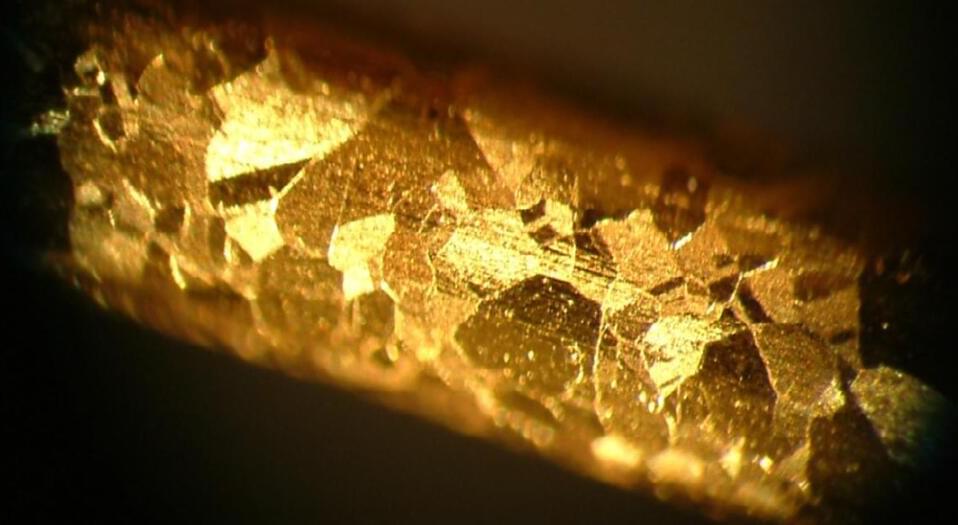

Non-toxic technology extracts more gold from ore

Gold is one of the world’s most popular metals. Malleable, conductive and non-corrosive, it’s used in jewelry, electronics, and even space exploration. But traditional gold production typically involves a famous toxin, cyanide, which has been banned for industrial use in several countries.

The wait for a scalable non-toxic alternative may now be over as a research team from Aalto University in Finland has successfully replaced cyanide in a key part of gold extraction from ore. The results are published in Chemical Engineering.

Study shows new chloride-based process recovers 84% of gold compared to the 64% recovered with traditional methods.

SpaceX Falcon Heavy Launch FINALLY SCHEDULED!

The SpaceX Falcon Heavy Launch which was scheduled for October 9 pushed to early next year. It’s finally happening, after 3 years of no activity, SpaceX schedules more than 4 launches to happen next year involving the SpaceX falcon heavy.

SpaceX’s next Falcon Heavy launching and dual-booster touchdown looks to be just around the corner for the first time in more than two years. After additional delays caused by its U.S. military cargo, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket’s next mission, which was previously intended for October, has been moved forward to early 2022. The Space Force’s USSF-44 mission was supposed to launch on Oct. 9 but it has been postponed.

In today’s video we look at how it all started, the developments made to date and we’re also going to take a peek into the future and see how glorious it is.

This is a tech channel that shows you the tech news and the trending of the future tech business and industry, we also talk about the enterprises inside, technology facts, entrepreneur’s brand stories, and their new toys including advanced products and their innovation stuff. We believe the new technology will take us to the next level and we’ll be more convenient in the future. If you’re looking for new tech info or industrial dynamics, make sure to hit that subscribe button!

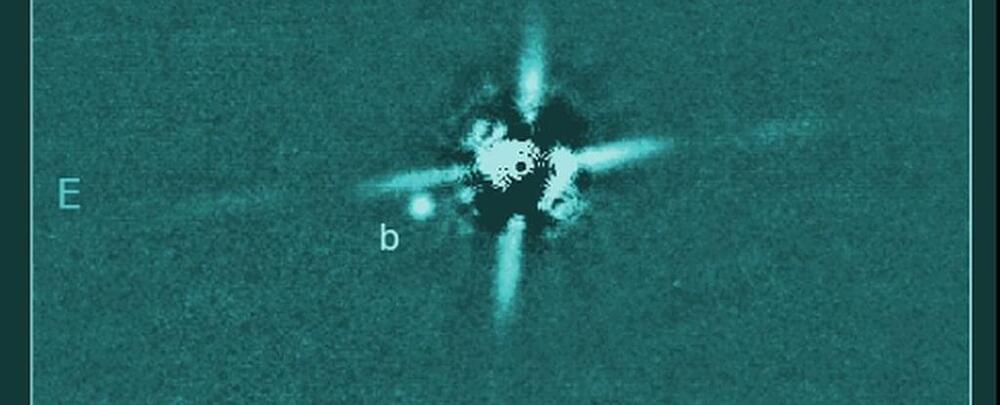

Jaw-Dropping Direct Image Shows a Baby Exoplanet Over 400 Light-Years Away

Just over 400 light-years away, a baby exoplanet is making its way into the Universe.

This, in itself, is not so unusual. We’ve detected thousands of exoplanets – planets outside the Solar System. Presumably they all had to be newborn at some point too. What makes this exoplanet special is that astronomers obtained a direct image of it – an almost vanishingly rare feat.

It’s named 2M0437b, and it’s one of the youngest exoplanets for which we have ever obtained a direct image. This could give us a new window into the planet formation process, which in turn could help us understand how the Solar System was born and evolved.