It’s the stuff of science fiction but it’s real.

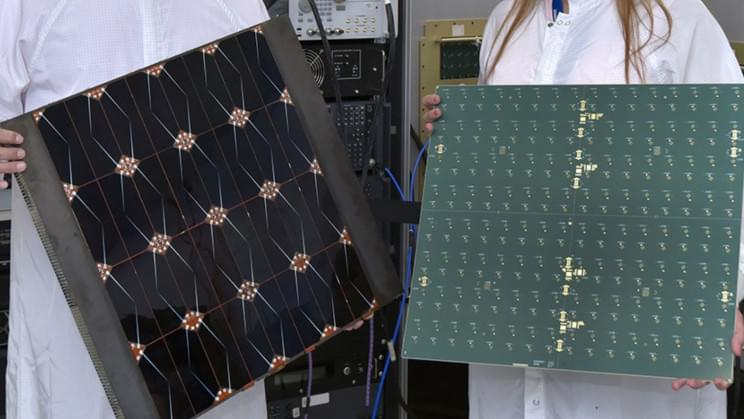

Although it may sound like science fiction, space-based solar power has started making headway with several projects underway. In February, we brought you news of technology firm Redwire acquiring Deployable Space Systems (DSS), a leading supplier of deployable solar arrays capable of enabling space missions with the intention of using them to deploy space-based solar power.

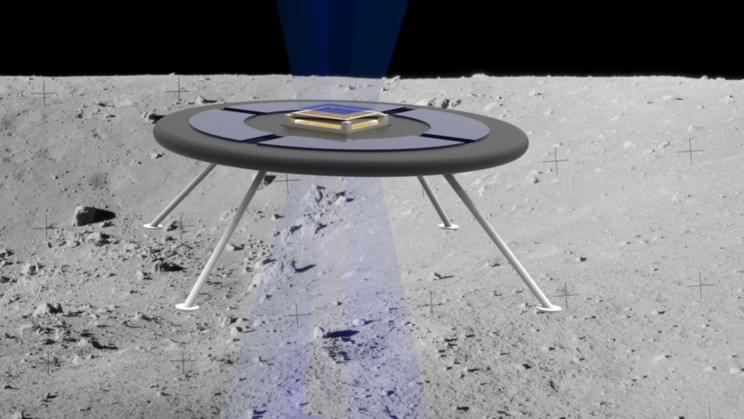

Meanwhile, last August we brought you further news, of Caltech’s Space Solar Power Project (SSPP) that collected solar power in space to be transmitted wirelessly to Earth offering energy unaffected by weather or time of day. The project promised to make solar power that could be continuously available anywhere on earth.