**A team of researchers affiliated with institutions in Singapore, China, Germany and the U.K., has developed an insect-computer hybrid system for use in search operations after disasters strike. **They have written a paper describing their system, now posted on the arXiv preprint server.

Because of the frequency of natural disasters such as earthquakes, fires and floods, scientists have been looking for better ways to help victims trapped in the rubble–people climbing over wreckage is both hazardous and inefficient. The researchers noted that small creatures such as insects move much more easily under such conditions and set upon the task of using a type of cockroach as a searcher to assist human efforts.

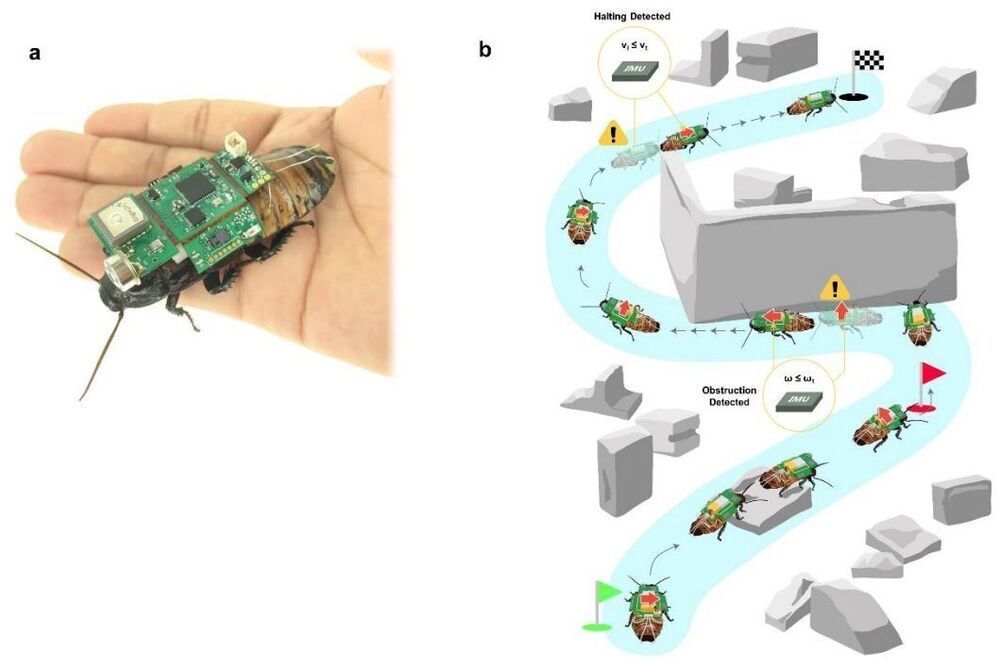

The system they came up with merges microtechnology with the natural skills of a live Madagascar hissing cockroach. These cockroaches are known for their dark brown and black body coloring and, of course, for the hissing sound they make when upset. They are also one of the few wingless cockroaches, which made them a good candidate for carrying a backpack.

The backpack created by the researchers consisted of five circuit boards connected together that hosted an IR camera, a communications chip, a CO2 sensor, a microcontroller, flash memory, a DAC converter and an IMU. The electronics-filled backpack was then affixed to the back of a cockroach. The researchers also implanted electrodes in the cockroach’s cerci–the antenna-like appendages on either side of its head. In its normal state, the cockroach uses its cerci to feel what is in its path and uses that information to make decisions about turning left or right. With the electrodes in place, the backpack could send very small jolts of electricity to the right or left cerci, inducing the cockroach to turn in a desired direction.

Testing involved setting the cockroach in a given spot and having it attempt to find a person laying in the vicinity. A general destination was preprogrammed into the hardware and then the system was placed into a test scenario, where it moved autonomously using cues from its sensor to make its way to the person serving as a test victim. The researchers found their system was able to locate the test human 94% of the time. They plan to improve their design with the goal of using the system in real rescue operations.