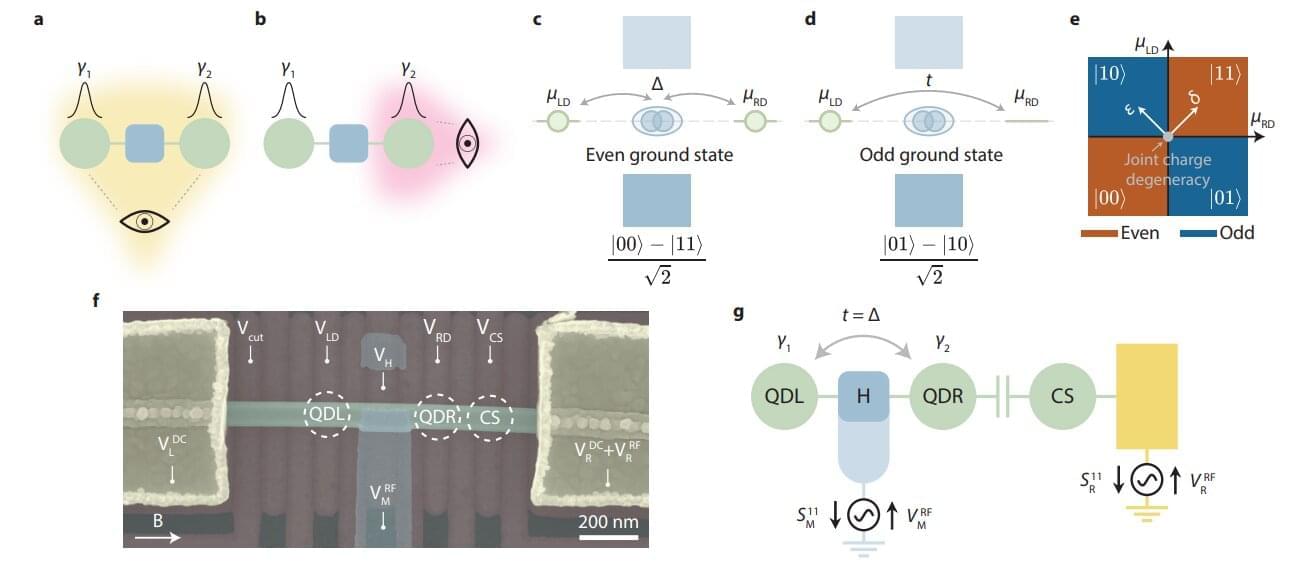

The race to build reliable quantum computers is fraught with obstacles, and one of the most difficult to overcome is related to the promising but elusive Majorana qubits. Now, an international team has read the information stored in these quantum bits. The findings are published in the journal Nature.

“This is a crucial advance,” explains Ramón Aguado, a Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) researcher at the Madrid Institute of Materials Science (ICMM) and one of the study’s authors.

“Our work is pioneering because we demonstrate that we can access the information stored in Majorana qubits using a new technique called quantum capacitance,” continues the scientist, who explains that this technique “acts as a global probe sensitive to the overall state of the system.”