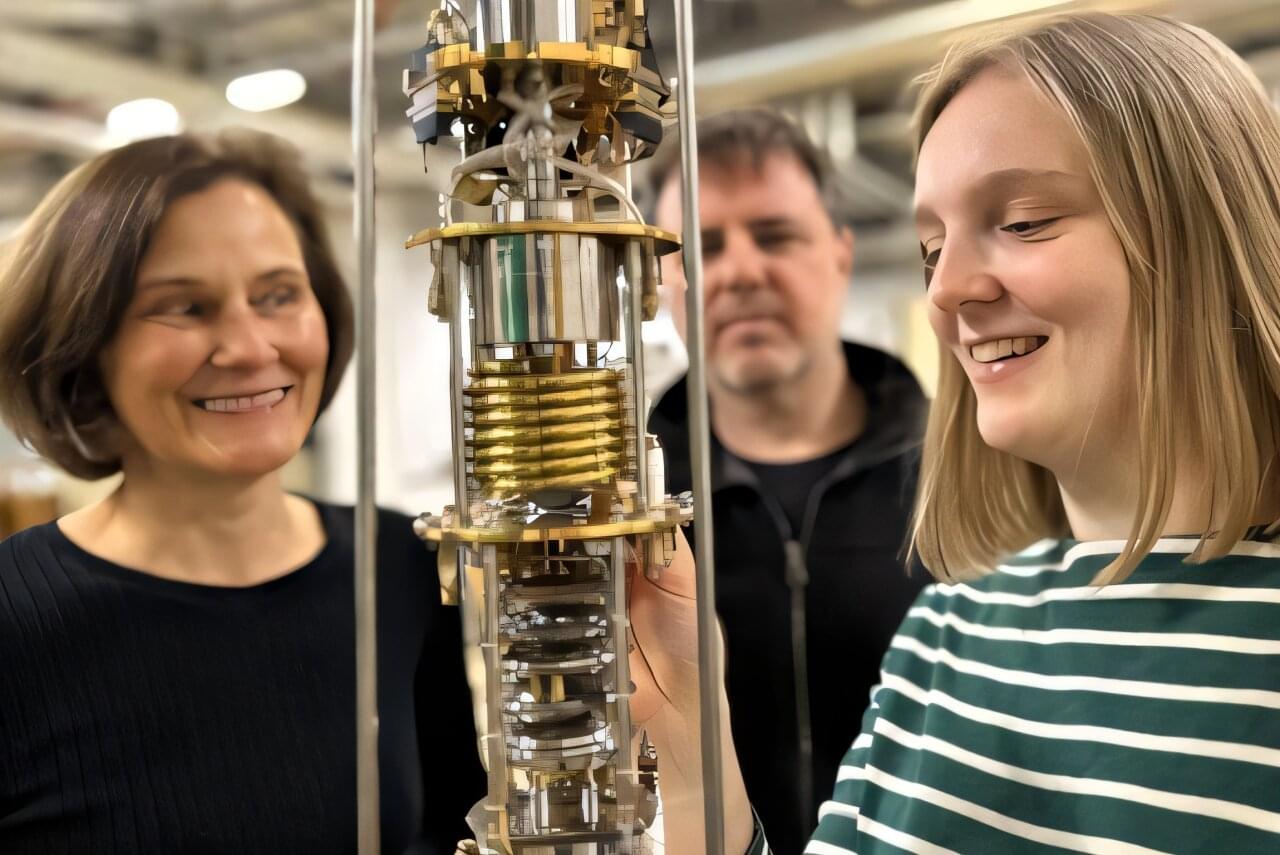

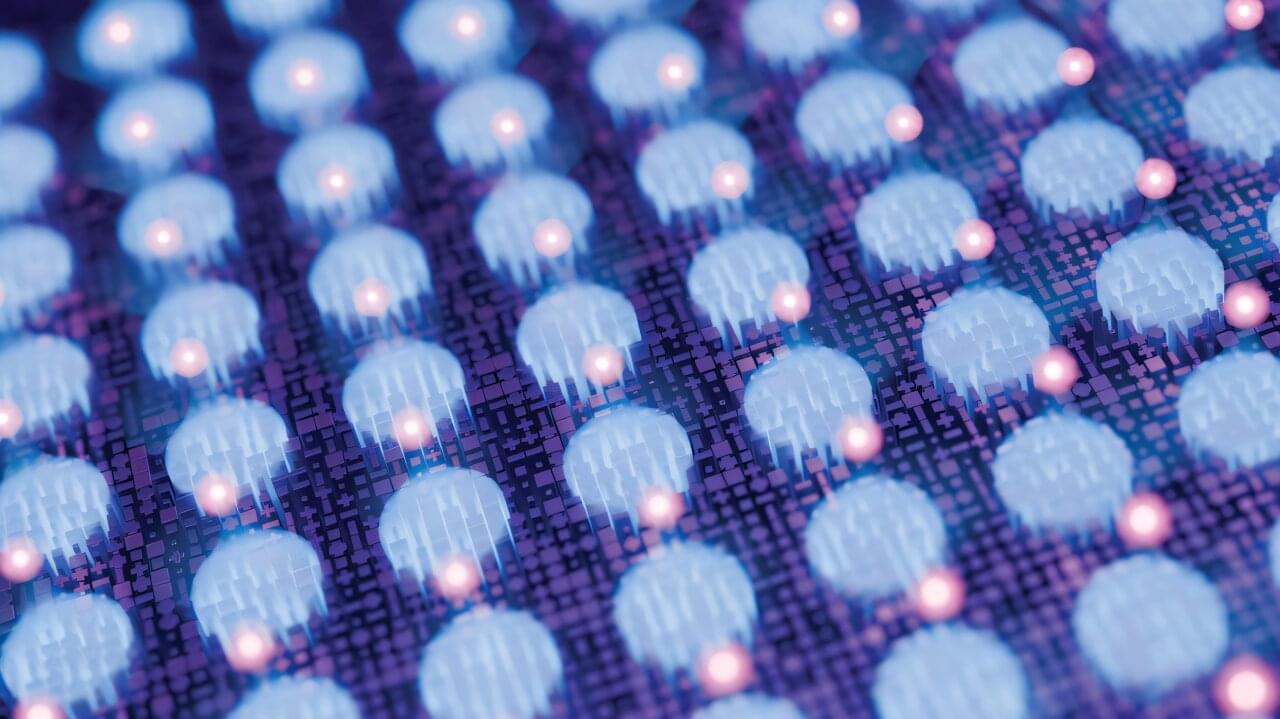

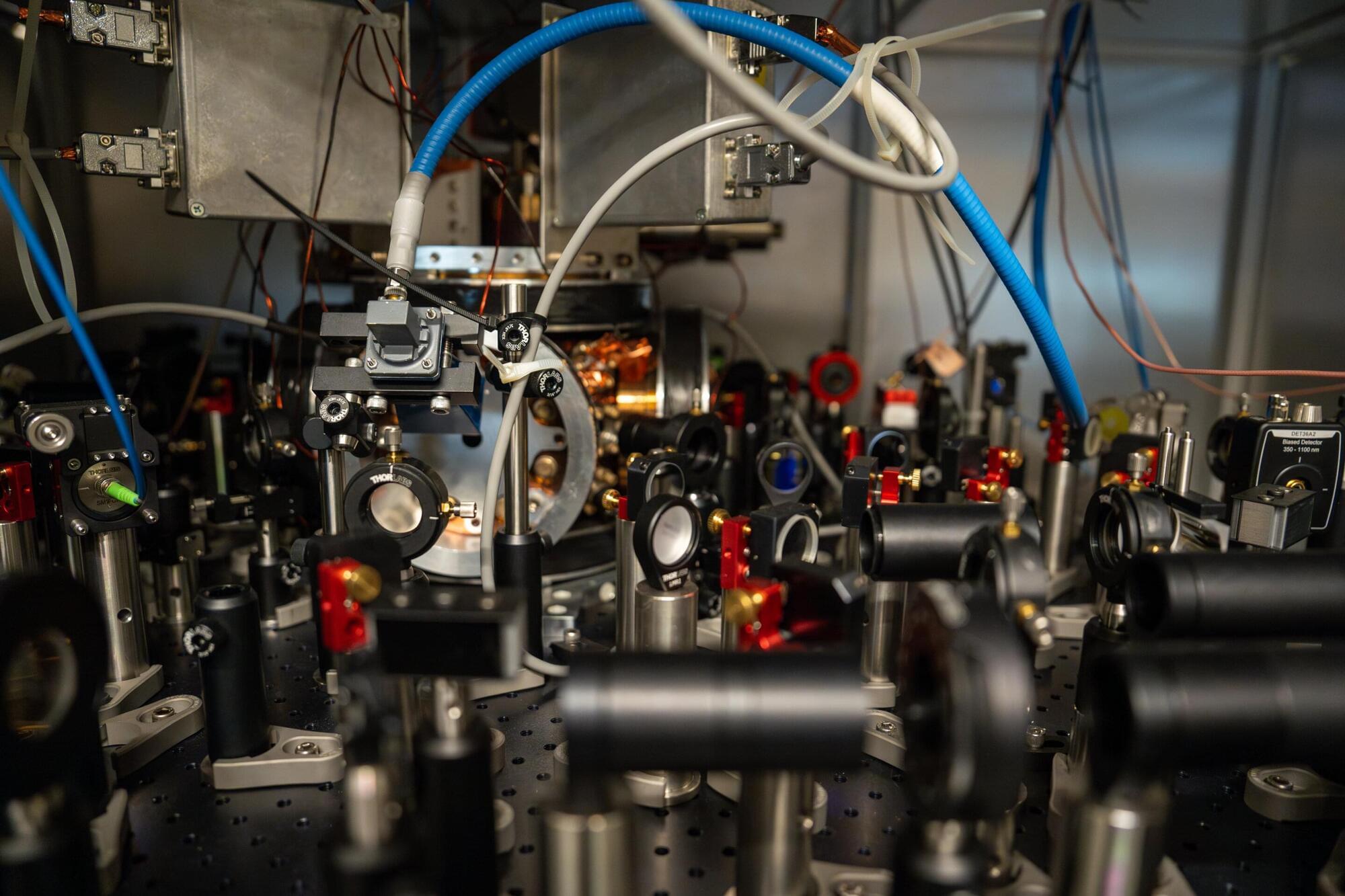

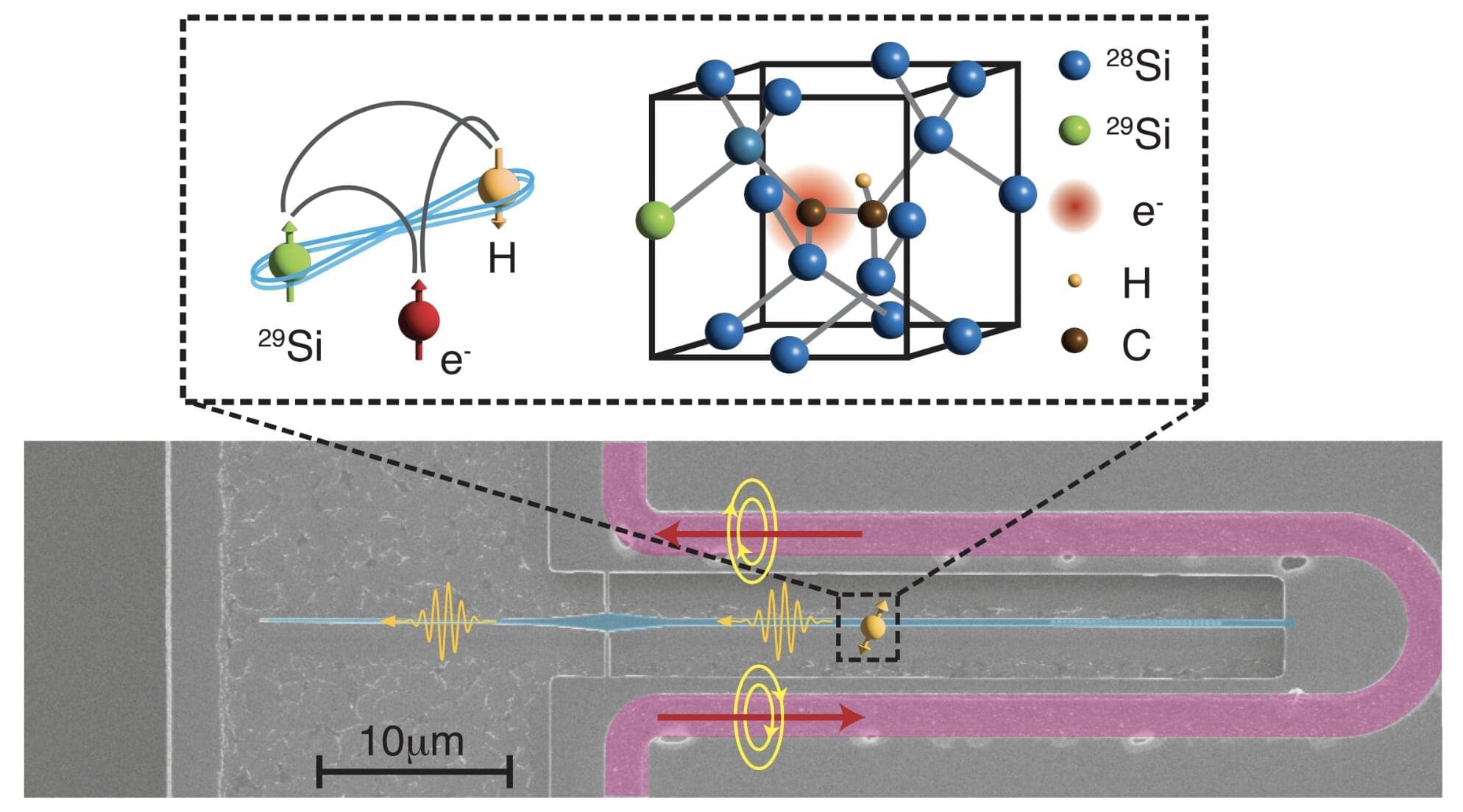

Quantum computers could rapidly solve complex problems that would take the most powerful classical supercomputers decades to unravel. But they’ll need to be large and stable enough to efficiently perform operations. To meet this challenge, researchers at MIT and elsewhere are developing quantum computers based on ultra-compact photonic chips. These chip-based systems offer a scalable alternative to some existing quantum computers, which rely on bulky optical equipment.

These quantum computers must be cooled to extremely cold temperatures to minimize vibrations and prevent errors. So far, such chip-based systems have been limited to inefficient and slow cooling methods.

Now, a team of researchers at MIT and MIT Lincoln Laboratory has implemented a much faster and more energy-efficient method for cooling these photonic chip-based quantum computers. Their approach achieved cooling to about 10 times below the limit of standard laser cooling.