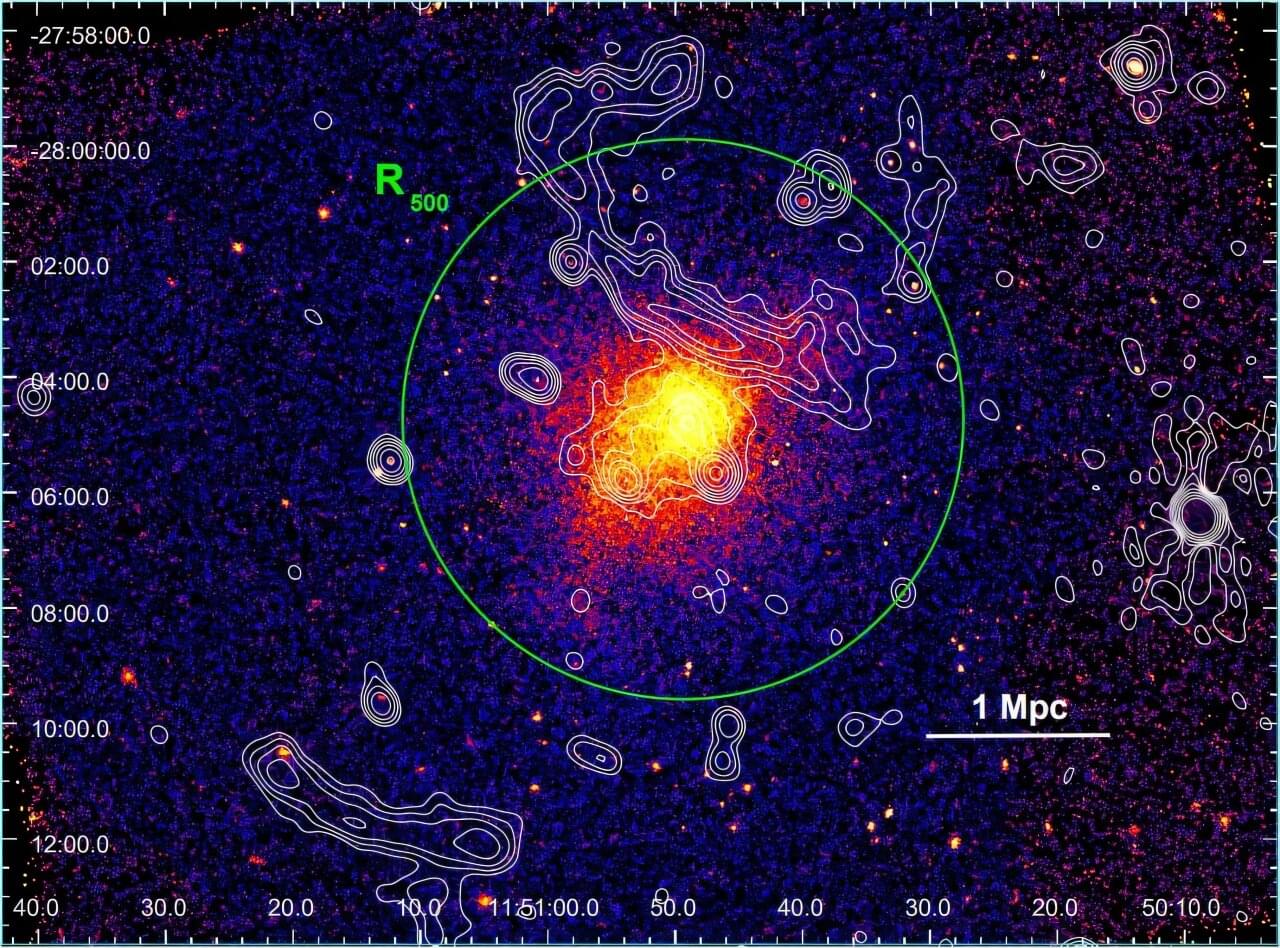

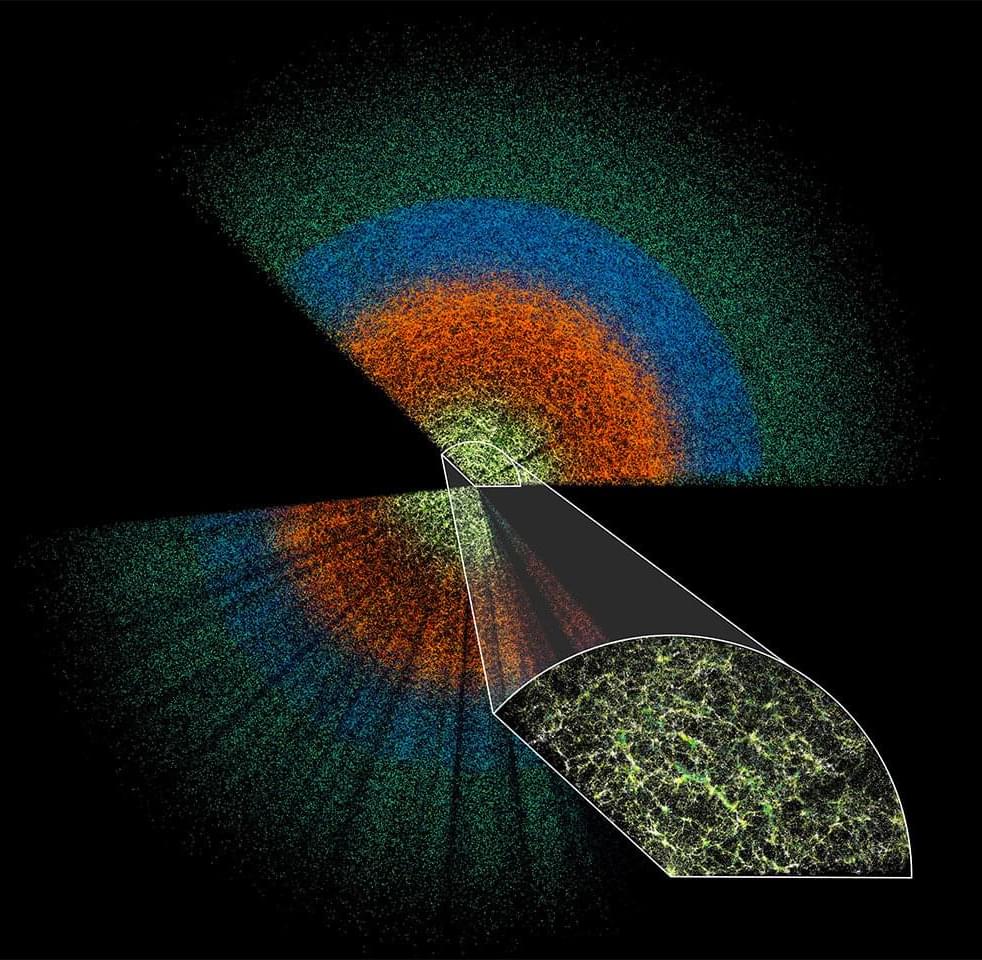

Using NASA’s Chandra X-ray observatory, astronomers have observed a massive and hot galaxy cluster known as PLCKG287.0+32.9 (or PLCKG287 for short). Results of the observational campaign, presented March 17 on the arXiv pre-print server, deliver important insights into the morphological and thermodynamical properties of this cluster.

Galaxy clusters contain up to thousands of galaxies bound together by gravity. They generally form as a result of mergers and grow by accreting sub-clusters. These processes provide an excellent opportunity to study matter in conditions that cannot be explored in laboratories on Earth. In particular, merging galaxy clusters could help us better understand the physics of shock and cold fronts seen in the diffuse intra-cluster medium, the cosmic ray acceleration in clusters, and the self-interaction properties of dark matter.

PLCKG287, also known as PSZ2 G286.98+32.90, is a galaxy cluster at a redshift of 0.38, with a mass of about 1.37 quadrillion solar masses and a temperature of 13 keV. The cluster has an X-ray luminosity in the 2–10 keV band at a level of 1.7 quattuordecillion erg/s.