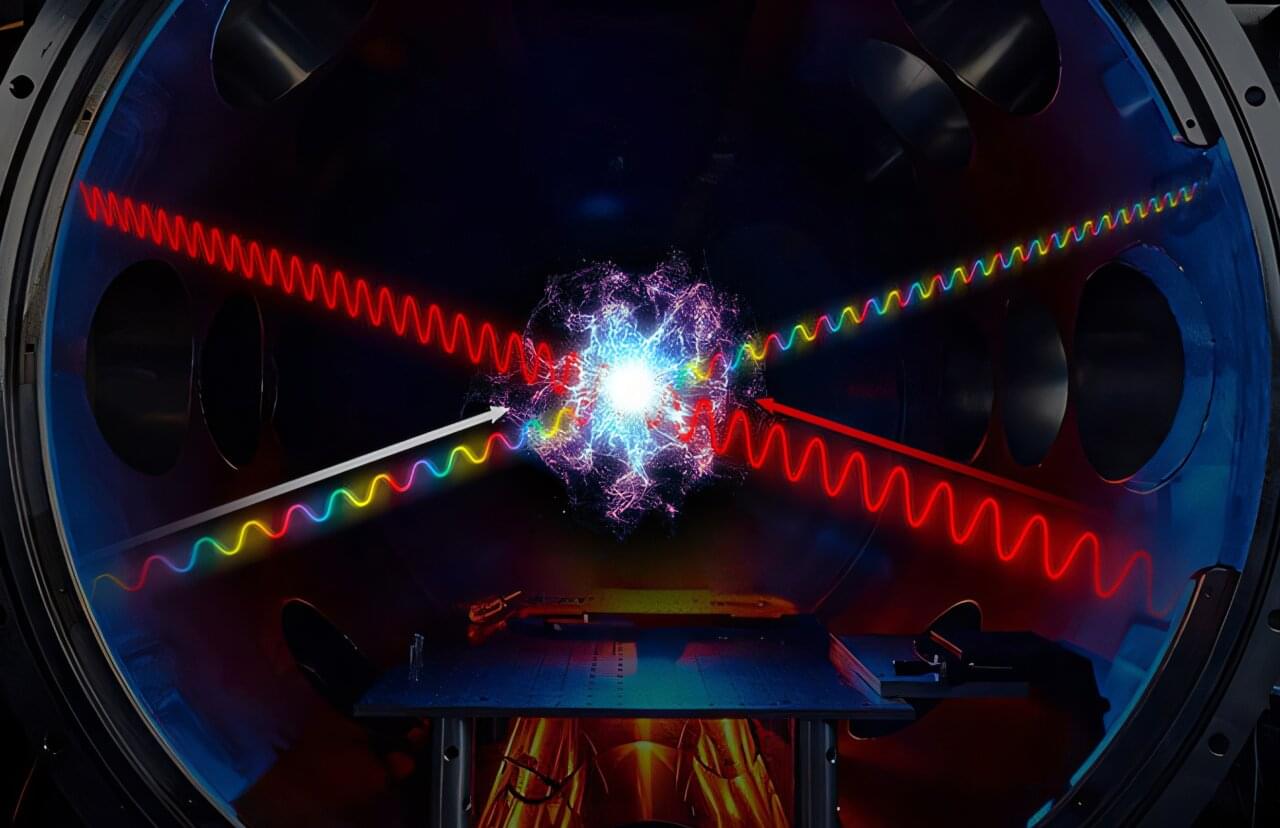

Modern technologies increasingly rely on light sources that can be reconfigured on demand. Think of microlasers that can quickly switch between different operating states—much like a car shifting gears—so that an optical chip can route signals, perform computations, or adapt to changing conditions in real time. The microlaser switching is not a smooth, leisurely process, but can be sudden and fast. Generally, nearly identical “candidate” lasing states compete with each other in a microcavity, and the laser may abruptly jump from one state to another when external conditions are tuned.

This raises a practical question: How fast can such a switch be, in principle? For physicists, it raises a deeper one: Does the switching follow a universal rule, like other phase transitions in nature?

A team at Peking University has now provided a clear picture of an ultrahigh-quality microcavity laser—the time the laser needs to complete a state switch follows a remarkably simple power-law rule. When the control knob is swept faster, the switch becomes faster—but not arbitrarily so. Instead, the switching time decreases with the square root of the sweep speed, corresponding to a robust exponent close to half. This result effectively sets a speed limit for how quickly such microlasers can “change gears.” The findings are published in Physical Review Letters.