Have you ever wondered what the universe looked like before the first stars were born? How did these stars form and how did they change the cosmos? These are some of the questions that the James Webb Space Telescope, or Webb for short, will try to answer. Webb is the most powerful and ambitious space telescope ever built, and it can observe the infrared light from the most distant and ancient objects in the universe, including the first stars. The first stars are extremely hard to find, because their light is very faint and redshifted by the expansion of the universe. But Webb has a huge mirror, a suite of advanced instruments, and a unique orbit that allows it to detect and study the first stars. By finding the first stars, Webb can learn a lot of information that can help us understand the early history and evolution of the universe, and test and refine the theoretical models and simulations of the first stars and their formation processes. Webb can also reveal new and unexpected phenomena and raise new questions about the first stars and their role in the universe. Webb is opening a new window to the cosmic dawn, where the first stars may shine. If you want to learn more about Webb and the first stars, check out this article1 from Universe Today. And don’t forget to like, share, and subscribe for more videos like this. Thanks for watching and see you next time. \

\

Chapters:\

00:00 Introduction\

01:09 Finding the first stars\

03:21 Technical challenges and scientific opportunities\

07:18 Challenges and limitations \

10:04 Outro\

10:31 Enjoy\

\

Best Telescopes for beginners:\

Celestron 70mm Travel Scope\

https://amzn.to/3jBi3yY\

\

Celestron 114LCM Computerized Newtonian Telescope\

https://amzn.to/3VzNUgU\

\

Celestron – StarSense Explorer LT 80AZ\

https://amzn.to/3jBRmds\

\

Visit our website for up-to-the-minute updates:\

www.nasaspacenews.com\

\

Follow us \

Facebook: / nasaspacenews \

Twitter: / spacenewsnasa \

\

Join this channel to get access to these perks:\

/ @nasaspacenewsagency \

\

#NSN #webb #firststars #cosmicdawn #astronomy #space #universe #infrared #telescope #nasa #esa #science #discovery #history #evolution #reionization #chemistry #physics #light #darkness #bigbang #galaxies #blackholes #supernovae #elements #life #youtube #video #education #entertainment #information #NASA #Astronomy

Category: physics – Page 145

The Biggest Discoveries in Computer Science in 2023

Quanta Magazine’s full list of the major computer science discoveries from 2023.

In 2023, artificial intelligence dominated popular culture — showing up in everything from internet memes to Senate hearings. Large language models such as those behind ChatGPT fueled a lot of this excitement, even as researchers still struggled to pry open the “black box” that describes their inner workings. Image generation systems also routinely impressed and unsettled us with their artistic abilities, yet these were explicitly founded on concepts borrowed from physics.

The year brought many other advances in computer science. Researchers made subtle but important progress on one of the oldest problems in the field, a question about the nature of hard problems referred to as “P versus NP.” In August, my colleague Ben Brubaker explored this seminal problem and the attempts of computational complexity theorists to answer the question: Why is it hard (in a precise, quantitative sense) to understand what makes hard problems hard? “It hasn’t been an easy journey — the path is littered with false turns and roadblocks, and it loops back on itself again and again,” Brubaker wrote. “Yet for meta-complexity researchers, that journey into an uncharted landscape is its own reward.”

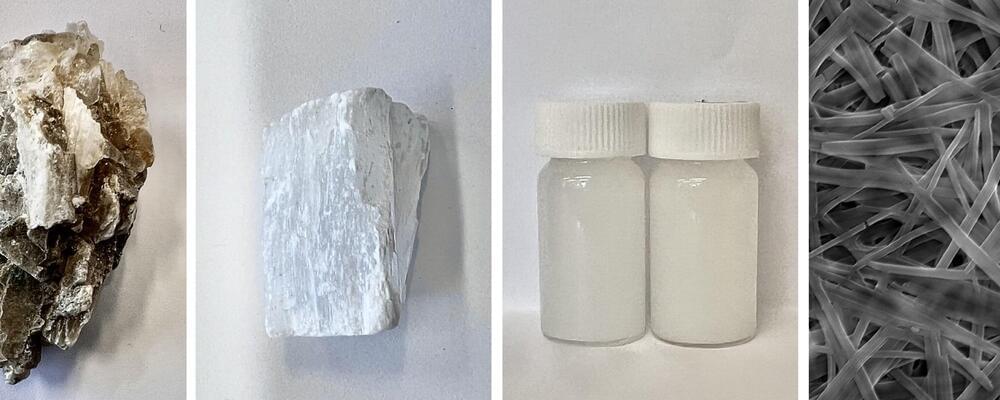

Using ‘waste’ product from recent NASA research, scientists create transformative nanomaterials

Researchers at the University of Sussex have discovered the transformative potential of Martian nanomaterials, potentially opening the door to sustainable habitation on the red planet.

Using resources and techniques currently applied on the International Space Station and by NASA, Dr. Conor Boland, a Lecturer in Materials Physics at the University of Sussex, led a research group that investigated the potential of nanomaterials—incredibly tiny components thousands of times smaller than a human hair —for clean energy production and building materials on Mars.

Taking what was considered a waste product by NASA and applying only sustainable production methods, including water-based chemistry and low-energy processes, the researchers have successfully identified electrical properties within gypsum nanomaterials—opening the door to potential clean energy and sustainable technology production on Mars.

Obtaining Tsallis entropy at the onset of chaos

Dr Alberto Robledo is a senior research scientist at Instituto de Física, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Robledo earned his undergraduate degree from UNAM and his doctorate from University of St Andrews, UK. He has conducted extensive research in the fields of statistical physics and complex systems for over fifty years.

This AI transformer tech-powered robot taught itself to walk

The robot is blind and cannot see its environment but can continue to balance and walk, even if an object is hurled at it.

UC researchers Ilija Radosavovic and Bike Zhang wondered if “reinforcement learning,” a concept made popular by large language models (LLMs) last year, could also teach the robot how to adapt to changing needs. To test their theory, the duo started with one of the most basic functions humans can perform — walking.

Transformer model for learning

The researchers started in the simulation world, running billions of scenarios in Isaac Gym, a high-performance GPU-based physics simulation environment. The algorithm in the simulator rewarded actions that mimicked human-like walking while punishing the ones that didn’t. Once the simulation perfected the task, it was transferred to a real-world humanoid bot that did not require further fine-tuning.

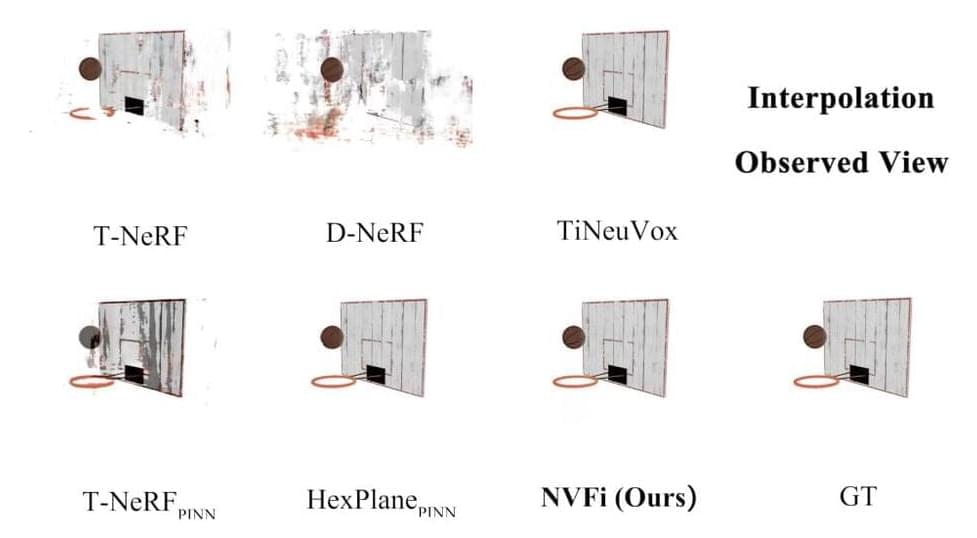

This AI Paper Introduces a Groundbreaking Method for Modeling 3D Scene Dynamics Using Multi-View Videos

NVFi tackles the intricate challenge of comprehending and predicting the dynamics within 3D scenes evolving over time, a task critical for applications in augmented reality, gaming, and cinematography. While humans effortlessly grasp the physics and geometry of such scenes, existing computational models struggle to explicitly learn these properties from multi-view videos. The core issue lies in the inability of prevailing methods, including neural radiance fields and their derivatives, to extract and predict future motions based on learned physical rules. NVFi ambitiously aims to bridge this gap by incorporating disentangled velocity fields derived purely from multi-view video frames, a feat yet unexplored in prior frameworks.

The dynamic nature of 3D scenes poses a profound computational challenge. While recent advancements in neural radiance fields showcased exceptional abilities in interpolating views within observed time frames, they fall short in learning explicit physical characteristics such as object velocities. This limitation impedes their capability to foresee future motion patterns accurately. Current studies integrating physics into neural representations exhibit promise in reconstructing scene geometry, appearance, velocity, and viscosity fields. However, these learned physical properties are often intertwined with specific scene elements or necessitate supplementary foreground segmentation masks, limiting their transferability across scenes. NVFi’s pioneering ambition is to disentangle and comprehend the velocity fields within entire 3D scenes, fostering predictive capabilities extending beyond training observations.

Researchers from The Hong Kong Polytechnic University introduce a comprehensive framework NVFi encompassing three fundamental components. First, a keyframe dynamic radiance field facilitates the learning of time-dependent volume density and appearance for every point in 3D space. Second, an interframe velocity field captures time-dependent 3D velocities for each point. Finally, a joint optimization strategy involving both keyframe and interframe elements, augmented by physics-informed constraints, orchestrates the training process. This framework offers flexibility in adopting existing time-dependent NeRF architectures for dynamic radiance field modeling while employing relatively simple neural networks, such as MLPs, for the velocity field. The core innovation lies in the third component, where the joint optimization strategy and specific loss functions enable precise learning of disentangled velocity fields without additional object-specific information or masks.

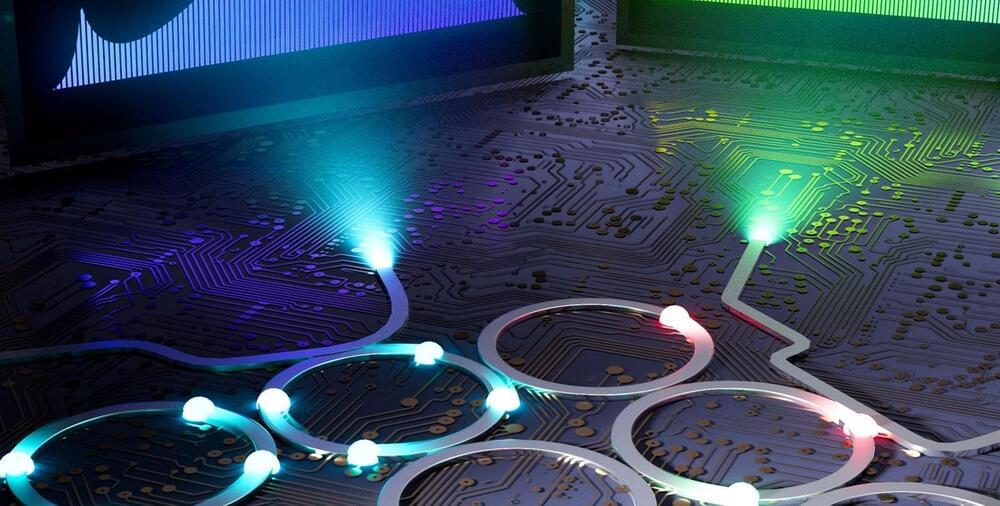

Conjoined ‘Racetracks’ make new Optical Device possible

Kerry Vahala and collaborators from UC Santa Barbara have found a unique solution to an optics problem. When we last checked in with Caltech’s Kerry Vahala three years ago, his lab had recently reported the development of a new optical device called a turnkey frequency microcomb that has applications in digital communications, precision time keeping, spectroscopy, and even astronomy.

This device, fabricated on a silicon wafer, takes input laser light of one frequency and converts it into an evenly spaced set of many distinct frequencies that form a train of pulses whose length can be as short as 100 femtoseconds (quadrillionths of a second). (The comb in the name comes from the frequencies being spaced like the teeth of a hair comb.)

Now Vahala (BS ’80, MS ’81, PhD ’85), Caltech’s Ted and Ginger Jenkins Professor of Information Science and Technology and Applied Physics and executive officer for applied physics and materials science, along with members of his research group and the group of John Bowers at UC Santa Barbara, have made a breakthrough in the way the short pulses form in an important new material called ultra-low-loss silicon nitride (ULL nitride), a compound formed of silicon and nitrogen.

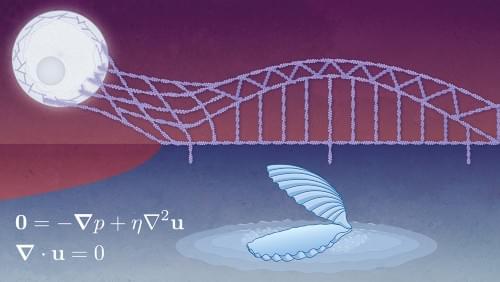

When is an Aurora not an Aurora?

While auroras occur at high latitude, the associated phenomena Steve and the picket fence occur farther south and at lower altitude. Their emissions also differ from aurora. A physics graduate student has proposed a physical mechanism behind these emissions, and a rocket launch to test the theory. She argues that an electric field in the upper atmosphere parallel to Earth’s magnetic field could explain the green picket fence spectrum and perhaps Steve and the enhanced aurora.

The shimmering green, red and purple curtains of the northern and southern lights — the auroras — may be the best-known phenomena lighting up the nighttime sky, but the most mysterious are the mauve and white streaks called Steve and their frequent companion, a glowing green “picket fence.”

First recognized in 2018 as distinct from the common auroras, Steve — a tongue-in-cheek reference to the benign name given a scary hedge in a 2006 children’s movie — and its associated picket fence were nevertheless thought to be caused by the same physical processes. But scientists were left scratching their heads about how these glowing emissions were produced.

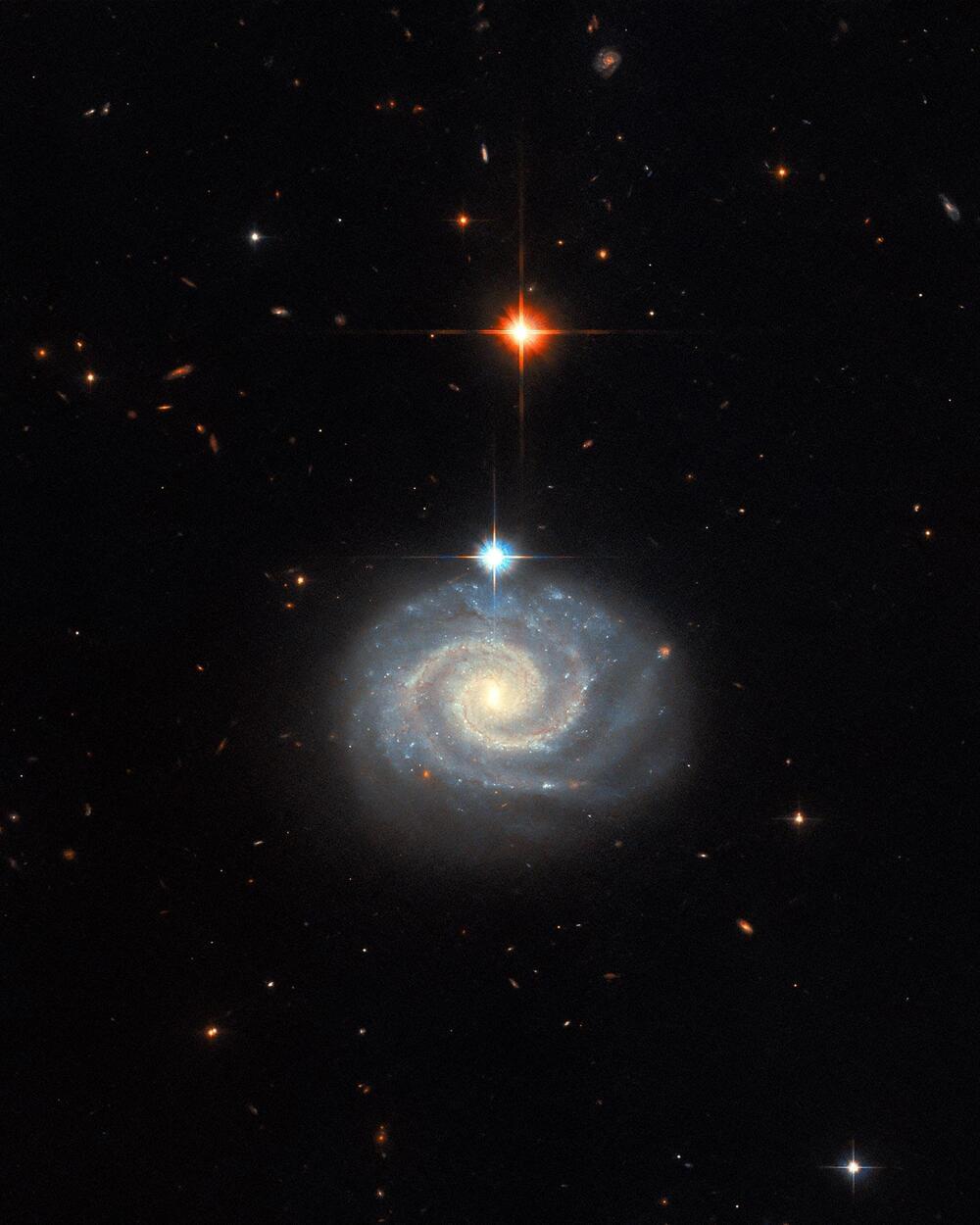

Defying Physics: “Forbidden” Emissions From a Spiral Galaxy

This whirling Hubble Space Telescope image features a bright spiral galaxy known as MCG-01–24-014, which is located about 275 million light-years from Earth. In addition to being a well-defined spiral galaxy, MCG-01–24-014 has an extremely energetic core, known as an active galactic nucleus (AGN), so it is referred to as an active galaxy.

Even more specifically, it is categorized as a Type-2 Seyfert galaxy. Seyfert galaxies host one of the most common subclasses of AGN, alongside quasars. Whilst the precise categorization of AGNs is nuanced, Seyfert galaxies tend to be relatively nearby ones where the host galaxy remains plainly detectable alongside its central AGN, while quasars are invariably very distant AGNs whose incredible luminosities outshine their host galaxies.