Duke engineers publish new method to use analog radio waves to boost energy-efficient edge AI.

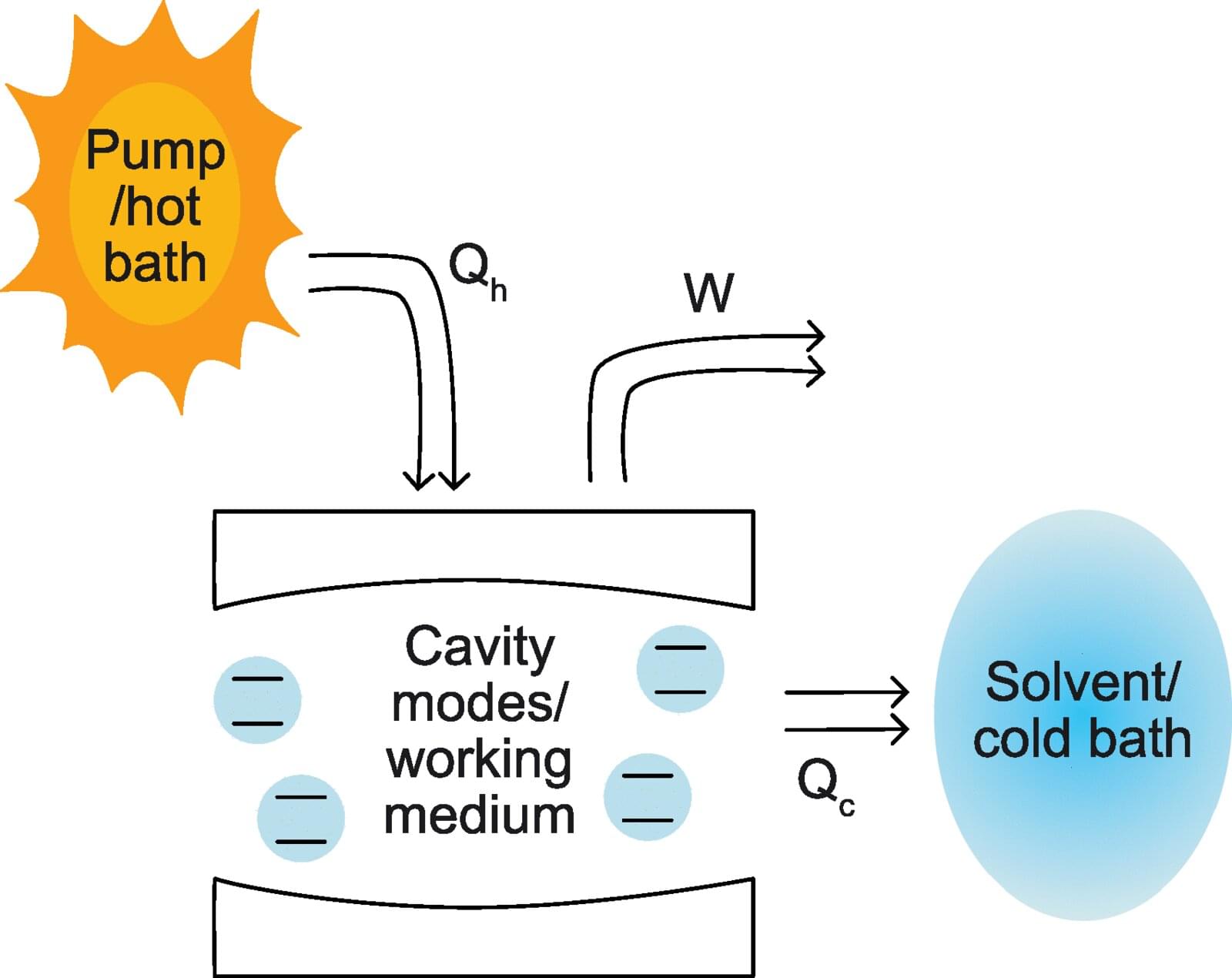

Physicists from Trinity College Dublin believe new insights into the behavior of light may offer a new means of solving one of science’s oldest challenges—how to turn heat into useful energy.

Their theoretical leap forwards, which will now be tested in the lab, could influence the development of specialized devices that would ultimately increase the amount of energy we can capture from sunlight (and lamps and LEDs) and then repurpose to perform useful tasks.

The work has just been published in the journal, Physical Review A.

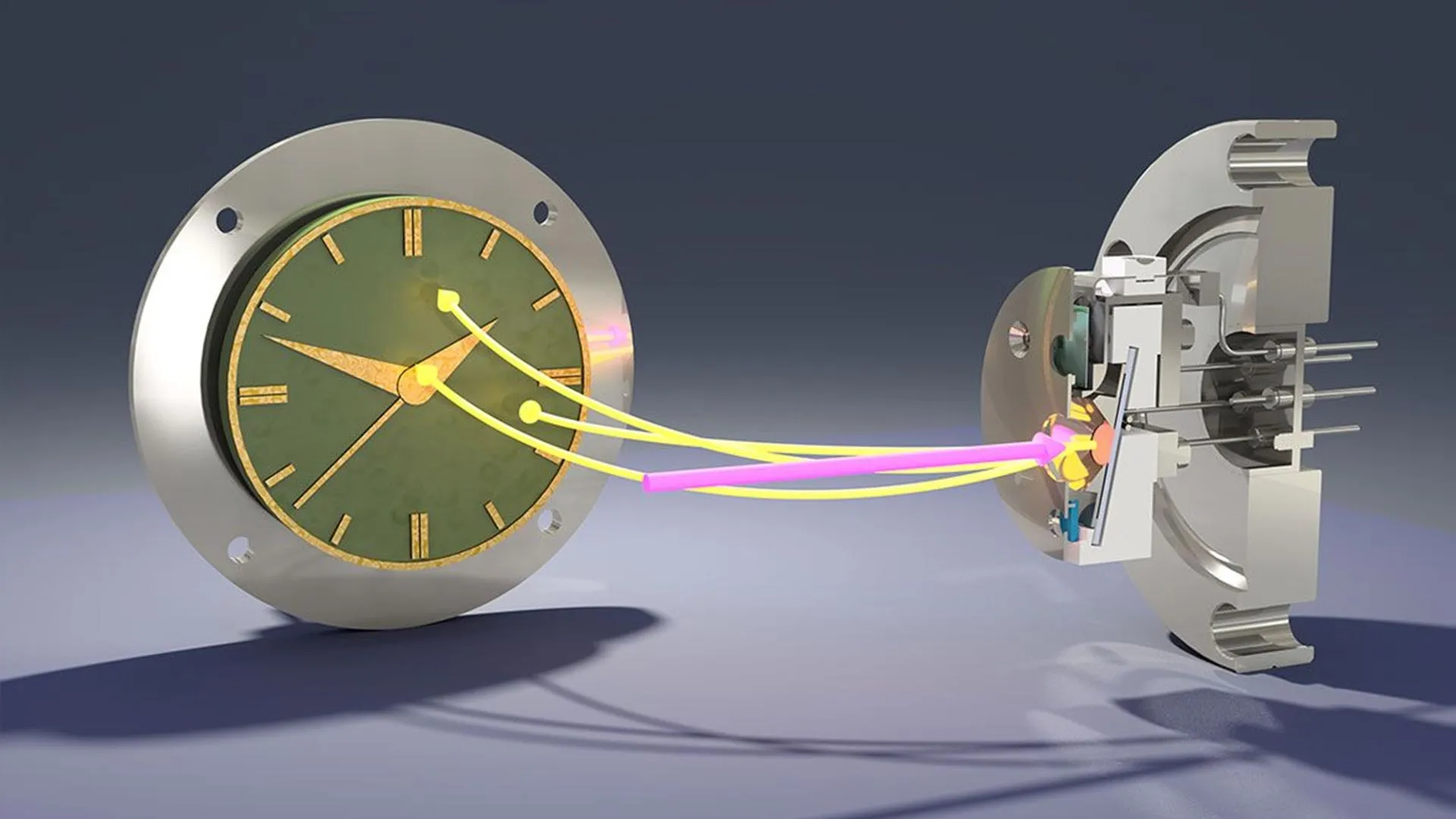

A team of physicists has discovered a surprisingly simple way to build nuclear clocks using tiny amounts of rare thorium. By electroplating thorium onto steel, they achieved the same results as years of work with delicate crystals — but far more efficiently. These clocks could be vastly more precise than current atomic clocks and work where GPS fails, from deep space to underwater submarines. The advance could transform navigation, communications, and fundamental physics research.

Thanks to their work from the 1980s and onward, John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton have helped lay the foundation for the machine learning revolution that started around 2010.

The development we are now witnessing has been made possible through access to the vast amounts of data that can be used to train networks, and through the enormous increase in computing power. Today’s artificial neural networks are often enormous and constructed from many layers. These are called deep neural networks and the way they are trained is called deep learning.

A quick glance at Hopfield’s article on associative memory, from 1982, provides some perspective on this development. In it, he used a network with 30 nodes. If all the nodes are connected to each other, there are 435 connections. The nodes have their values, the connections have different strengths and, in total, there are fewer than 500 parameters to keep track of. He also tried a network with 100 nodes, but this was too complicated, given the computer he was using at the time. We can compare this to the large language models of today, which are built as networks that can contain more than one trillion parameters (one million millions).

The Fine-Tuning Argument is often seen as the best argument for the existence of God. Here we have assembled some of the world’s top physicists and philosophers to offer a reply. Not every critic of the argument comes from the same perspective. Some doubt there is a problem to be solved whilst others agree it is a genuine problem but think there are better solutions than the God hypothesis. Some like the multiverse and anthropics other don’t. We have tried to represent these different approaches and so it should be taken as given, that not all of the talking heads agree with each other. Nevertheless, they all share the view that the fine-tuning argument for God does not work. Nor are all the objectors atheist, Hans Halvorson offers what we think is a strong theological objection to the argument. This film does not try to argue that God doesn’t exist only that the fine-tuning argument is not a good reason to believe in God. Most of the footage was filmed exclusively for this film with some clips being re-used from our Before the Big Bang series, which can be viewed here: • Before the Big Bang 5: The No Boundary Pro… All of the critics of the fine tuning argument that appear were sent a draft of the film more than a month before release and asked for any objections either to their appearance, the narration or any other aspect of the film. No objections were raised, and many replies were extremely positive and encouraging. A timeline of the subjects covered is below:

(We define God as a perfect Omni immaterial mind as for example modern Christians and Muslims advocate, there are other conceptions of God which our video does not address).

Just to be clear, this is a polemical film arguing against the fine tuning argument.

Timecodes.

0:00 Introduction.

4:11 The universe as a roll of the dice.

6:15 what is probability?

7:28 probability problems.

9:25 measure problem.

15:45 deceptive probabilities.

20:23 the flatness problem.

22:14 counterfactuals versus probabilities.

23:59 fine tuning versus God.

37:02 necessity.

38:53 multiverse and anthropics.

47:34 Boltzmann brains.

49:45 Entropy.

52:45 Cosmological Natural Selection.

59:10 conclusion.

In this Oct. 20, 2025, photo, tiny ball bearings surround a larger central bearing during the Fluid Particles experiment, conducted inside the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) aboard the International Space Station’s Destiny laboratory module.

A bulk container installed in the MSG, filled with viscous fluid and embedded particles, is subjected to oscillating frequencies to observe how the particles cluster and form larger structures in microgravity. Insights from this research may advance fire suppression, lunar dust mitigation, and plant growth in space. On Earth, the findings could inform our understanding of pollen dispersion, algae blooms, plastic pollution, and sea salt transport during storms.

In addition to uncovering potential benefits on Earth, research done aboard the space station helps inform long-duration missions like Artemis and future human expeditions to Mars.