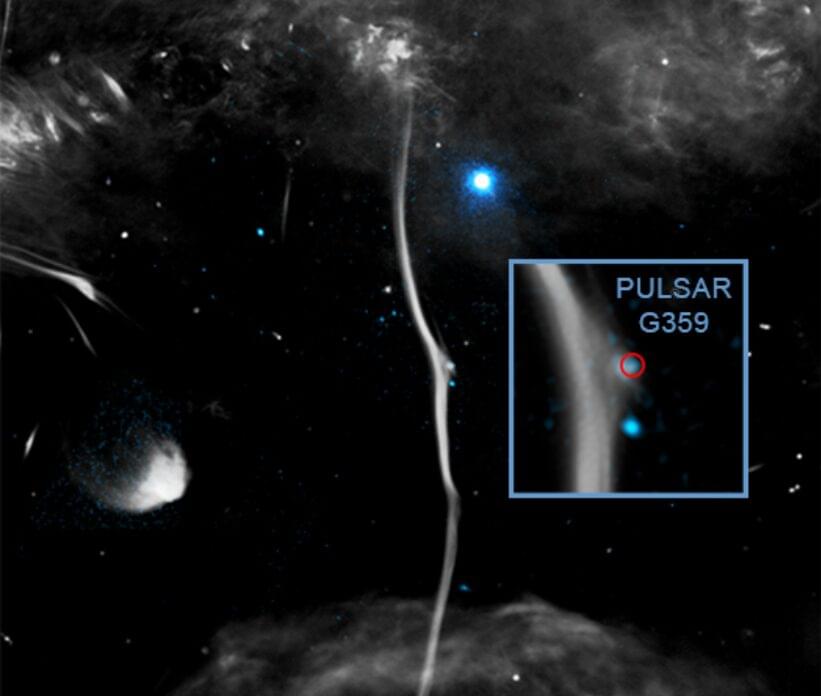

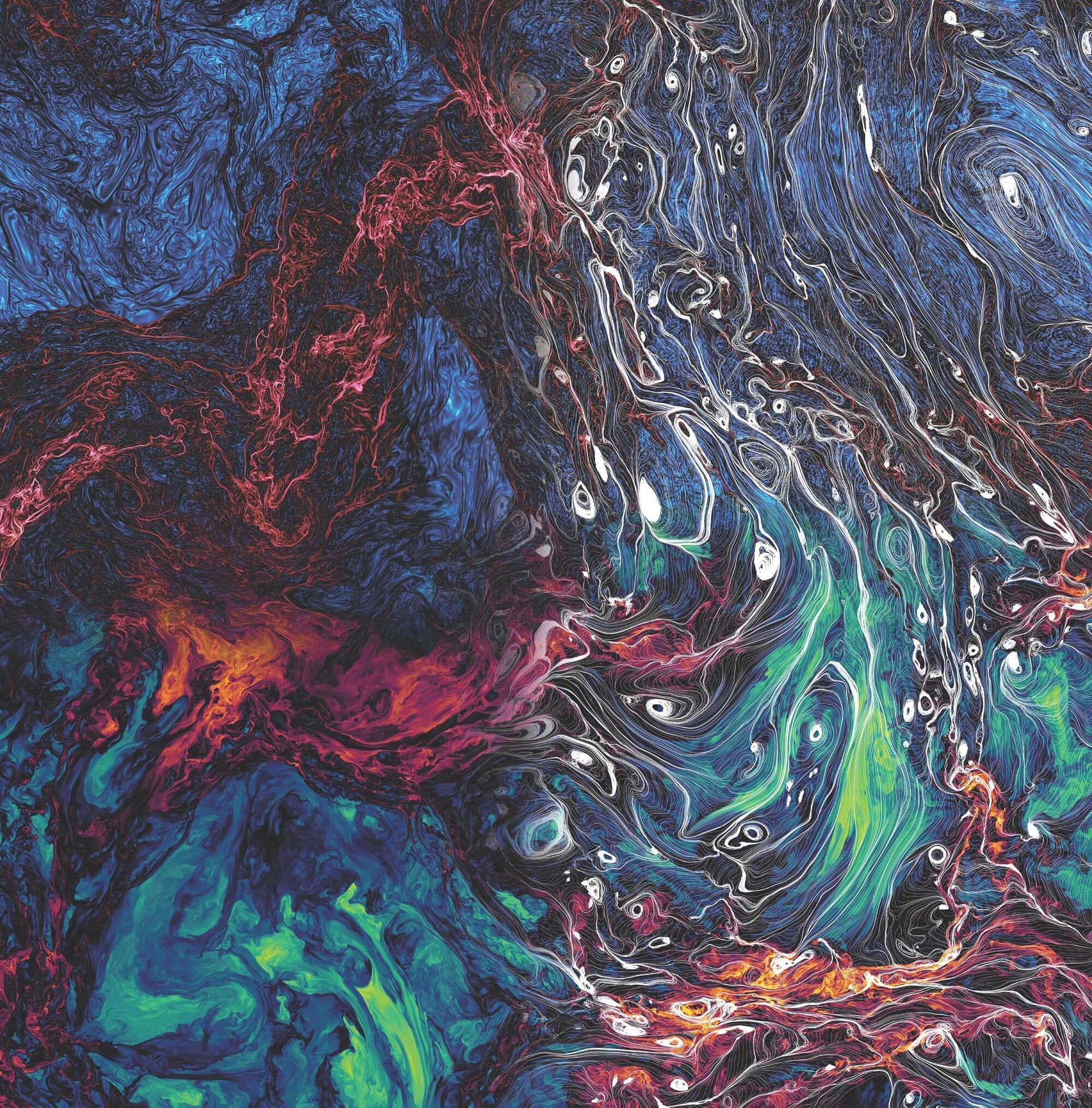

Astronomers have discovered a likely explanation for a fracture in a huge cosmic “bone” in the Milky Way galaxy, using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and radio telescopes.

The bone appears to have been struck by a fast-moving, rapidly spinning neutron star, or a pulsar. Neutron stars are the densest known stars and form from the collapse and explosion of massive stars. They often receive a powerful kick from these explosions, sending them away from the explosion’s location at high speeds.

Enormous structures resembling bones or snakes are found near the center of the galaxy. These elongated formations are seen in radio waves and are threaded by magnetic fields running parallel to them. The radio waves are caused by energized particles spiraling along the magnetic fields.