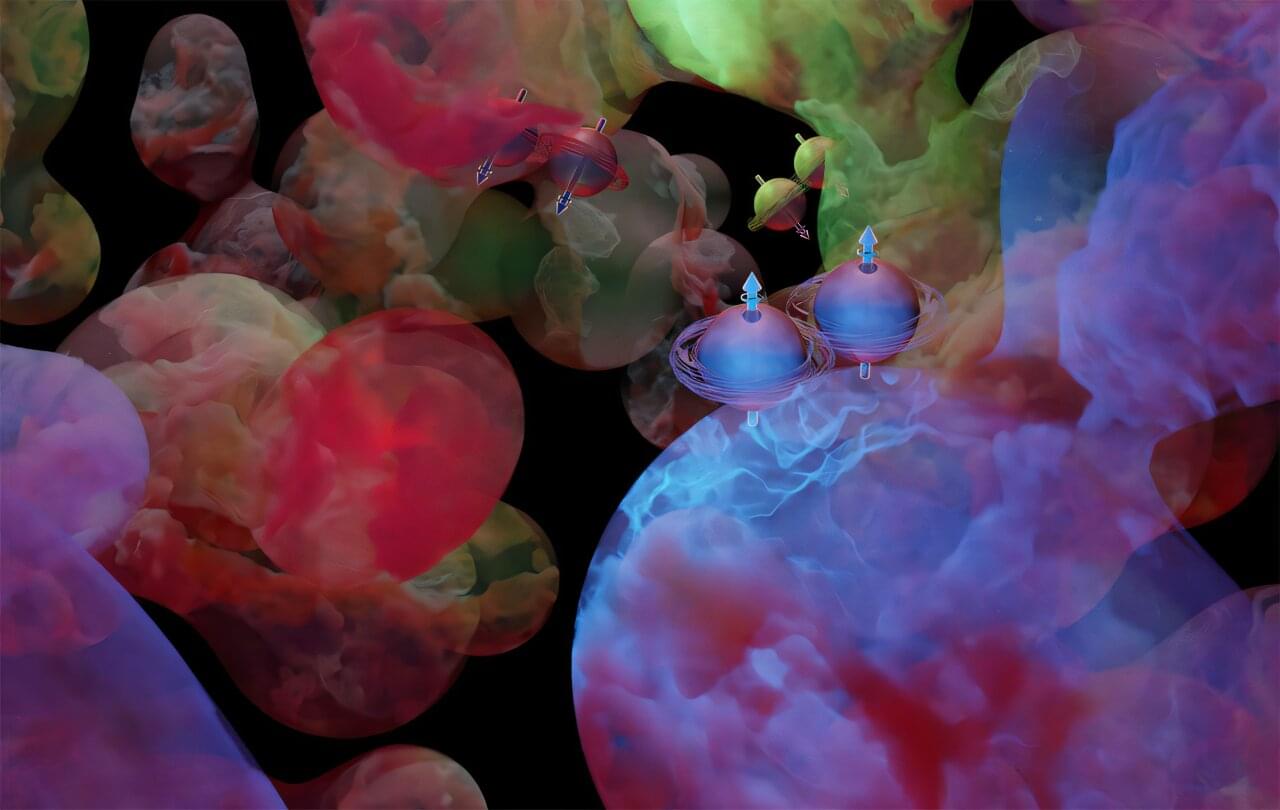

Right now, molecules in the air are moving around you in chaotic and unpredictable ways. To make sense of such systems, physicists use a law known as the Boltzmann distribution, which, rather than describe exactly where each particle is, describes the chance of finding the system in any of its possible states. This allows them to make predictions about the whole system even though the individual particle motions are random. It’s like rolling a single die: Any one roll is unpredictable, but if you keep rolling it again and again, a pattern of probabilities will emerge.

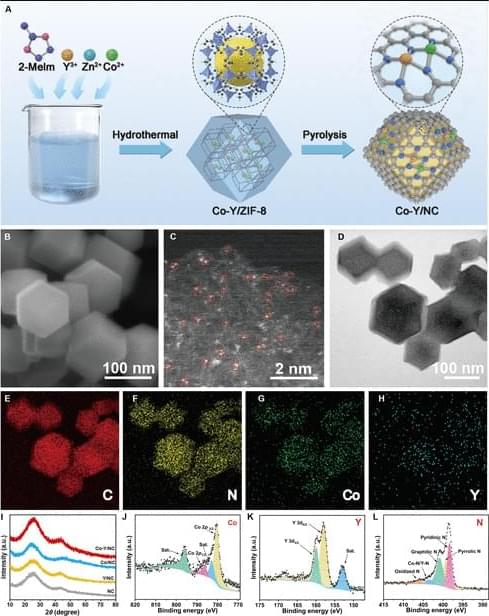

Developed in the latter half of the 19th century by Ludwig Boltzmann, an Austrian physicist and mathematician, this Boltzmann distribution is used widely today to model systems in many fields, ranging from AI to economics, where it is called “multinomial logit.”

Now, economists have taken a deeper look at this universal law and come up with a surprising result: The Boltzmann distribution, their mathematical proof shows, is the only law that accurately describes unrelated, or uncoupled, systems.