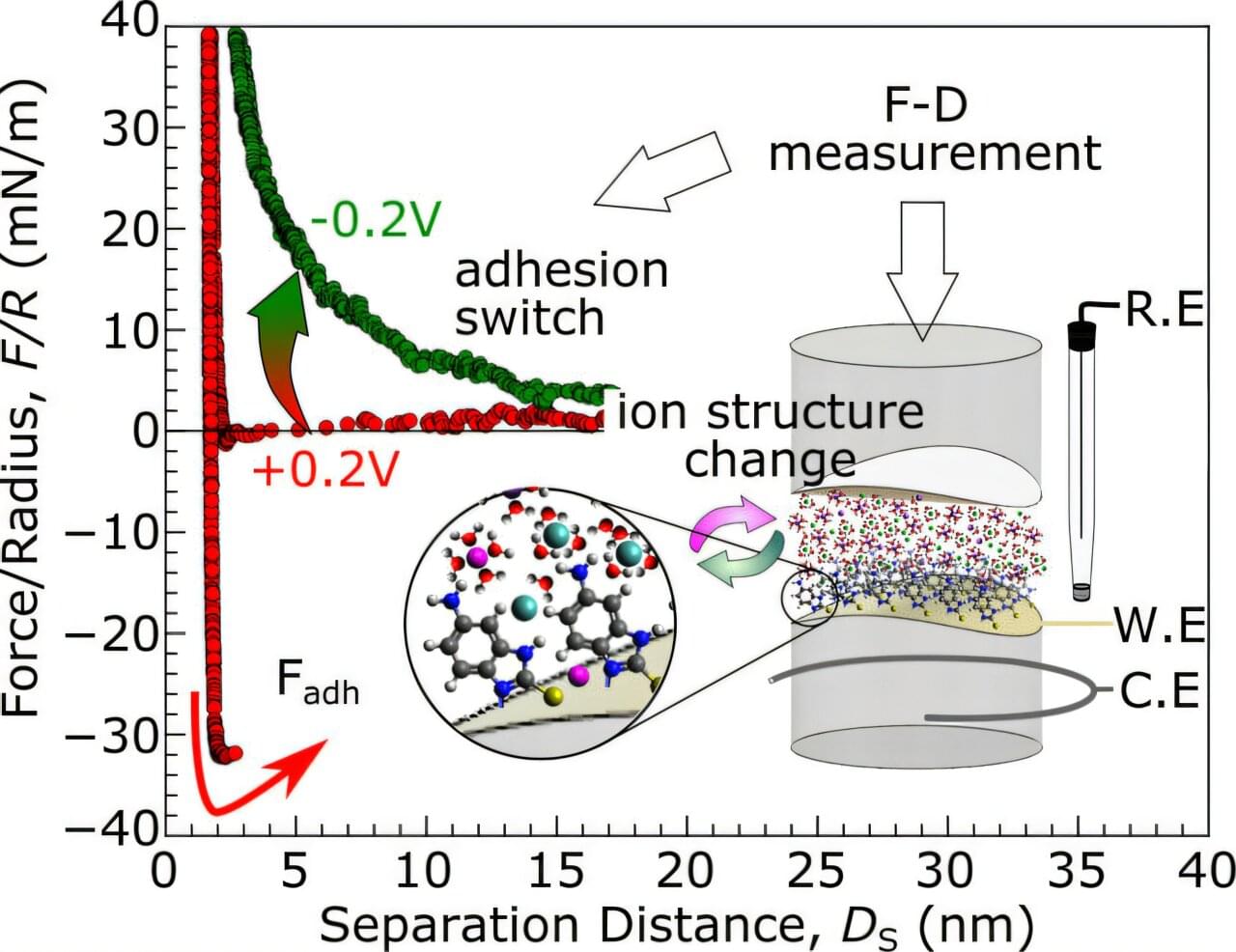

When a system undergoes a transformation, yet an underlying physical property remains unchanged, this property is referred to as “symmetry.” Spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) occurs when a system breaks out of this symmetry when it is most stable or in its lowest-possible energy state.

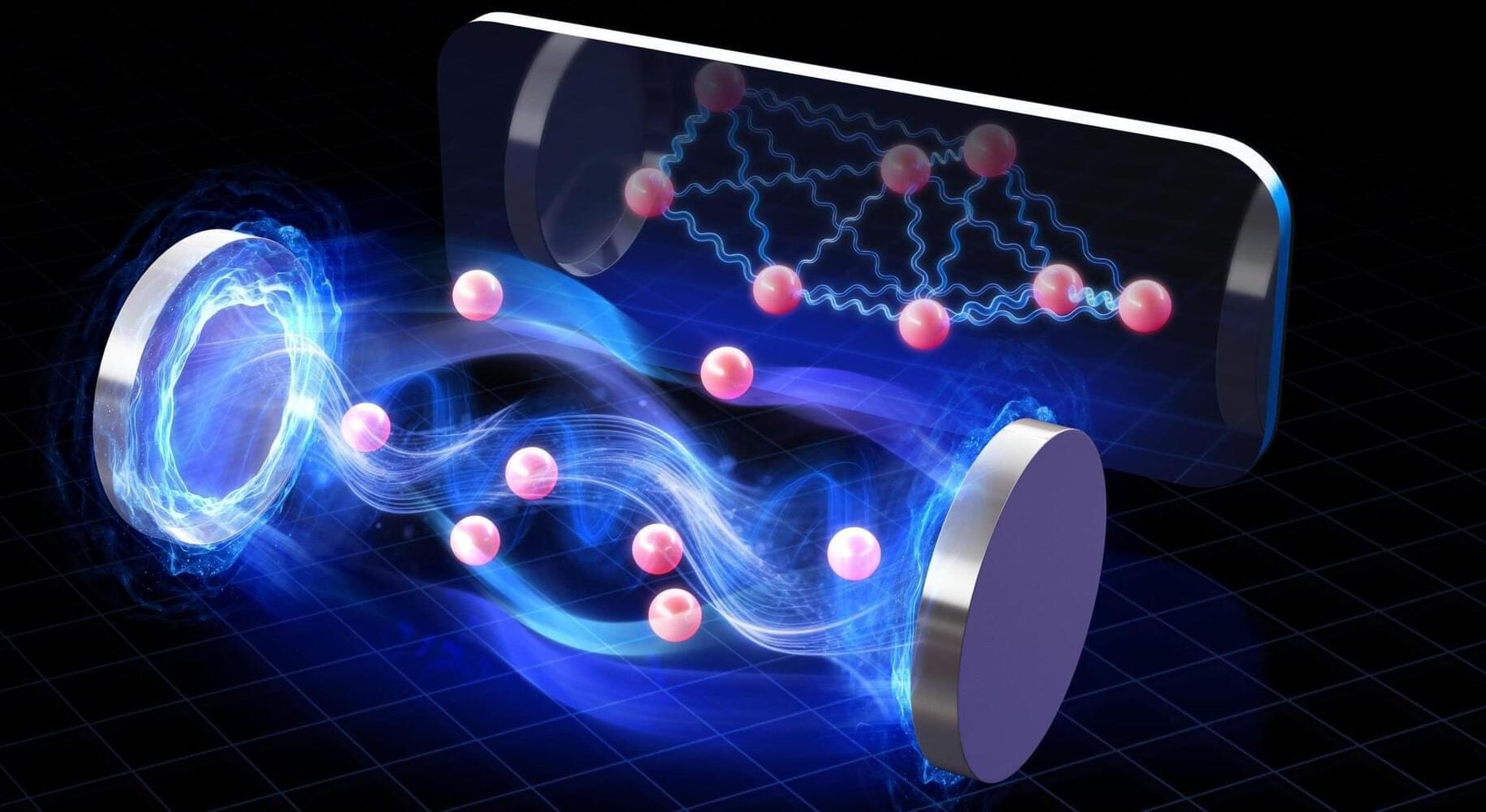

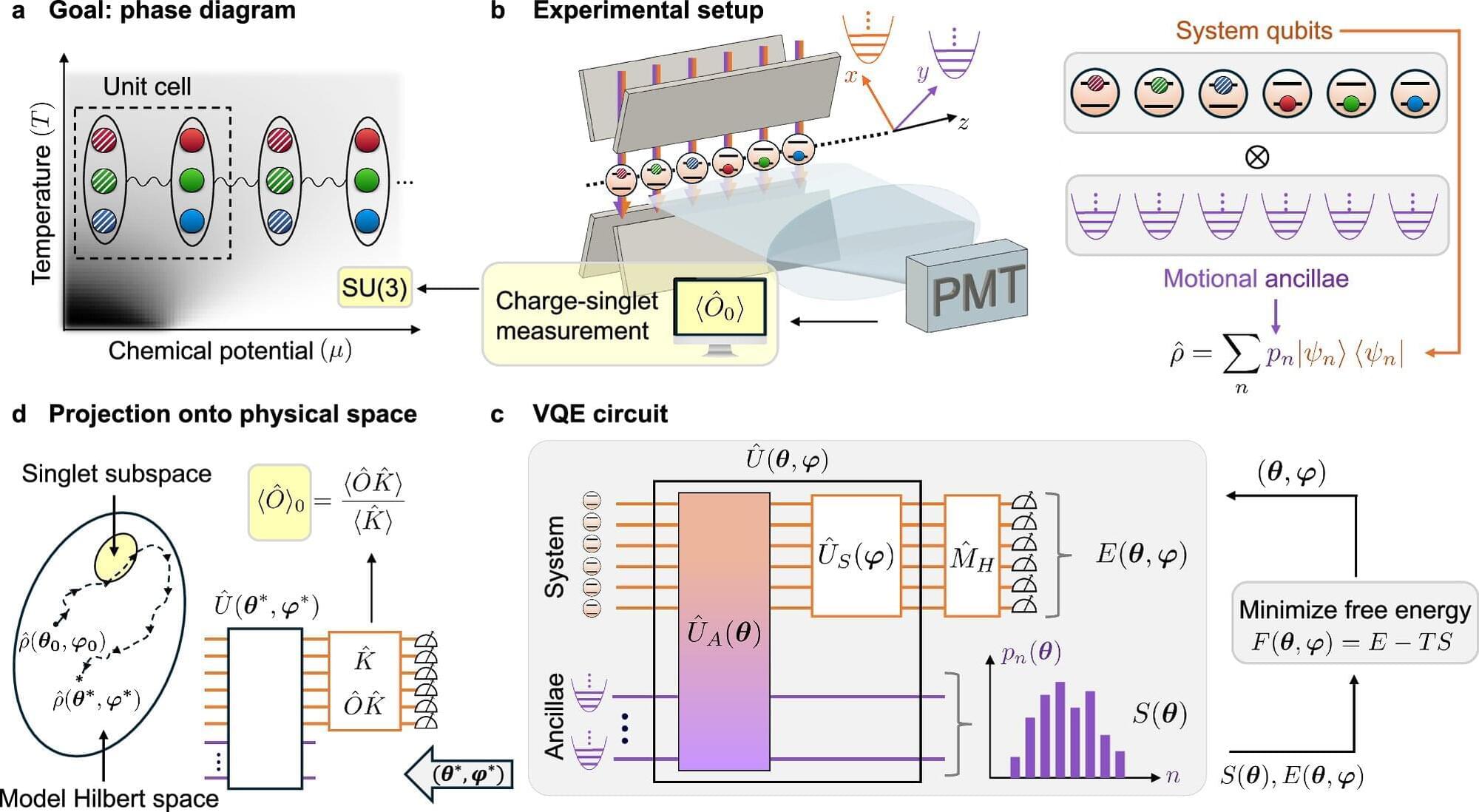

Recently, physicists realized that a new type of SSB can occur in open quantum systems, systems driven by quantum mechanical effects that can exchange information, energy or particles with their surrounding environment. Specifically, they realized that the symmetry in these systems can be “strong” or “weak.”

A strong symmetry entails that both the open system and its surrounding environment individually obey the symmetry. In contrast, a weak symmetry takes place when the system and the environment only follow a symmetry when they are taken together.