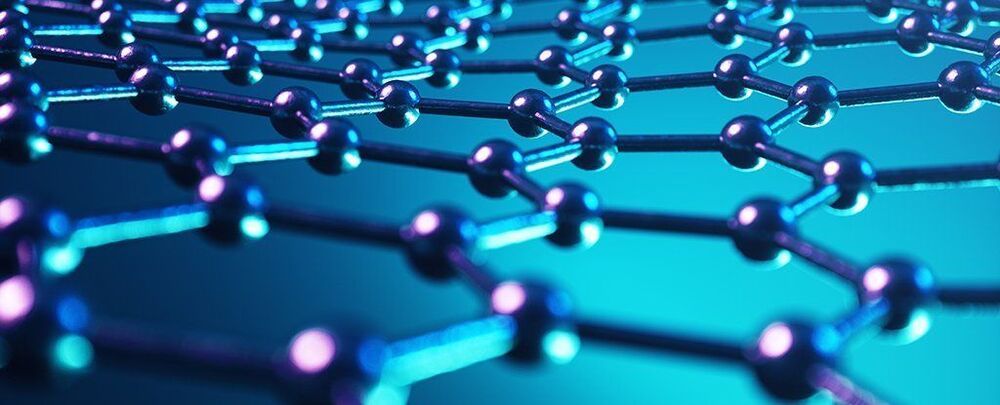

Graphene continues to dazzle us with its strength and its versatility – exciting new applications are being discovered for it all the time, and now scientists have found a way of manipulating the wonder material so that it can better filter impurities out of water.

The two-dimensional material comprised of carbon atoms has been studied as a way of cleaning up water before, but the new method could offer the most promising approach yet. It’s all down to the exploitation of what are known as van der Waals gaps: the tiny spaces that appear between 2D nanomaterials when they’re layered on top of each other.

These nanochannels can be used in a variety of ways, which scientists are now exploring, but the thinness of graphene causes a problem for filtration: liquid has to spend much of its time travelling along the horizontal plane, rather than the vertical one, which would be much quicker.