Where did all the antimatter go? After the Big Bang, matter and antimatter should have been created in equal amounts. Why we live in a universe of matter, with very little antimatter, remains a mystery. The excess of matter could be explained by the violation of charge-parity (CP) symmetry, which essentially means that certain processes that involve particles behave differently to those that involve their antiparticles.

However, the CP-violating processes that have been observed so far are insufficient to explain the matter–antimatter asymmetry in the universe. New sources of CP violation must be out there—and might be hiding in interactions involving the Higgs boson. In the Standard Model of particle physics, Higgs-boson interactions with other particles conserve CP symmetry. If researchers find signs of CP violation in these interactions, they could be a clue to one of the universe’s oldest mysteries.

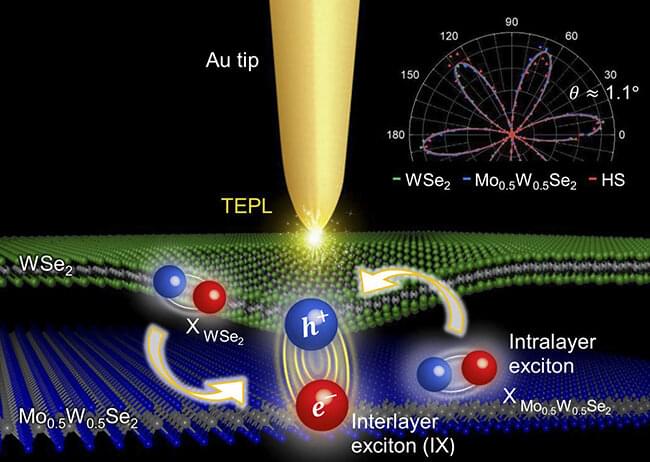

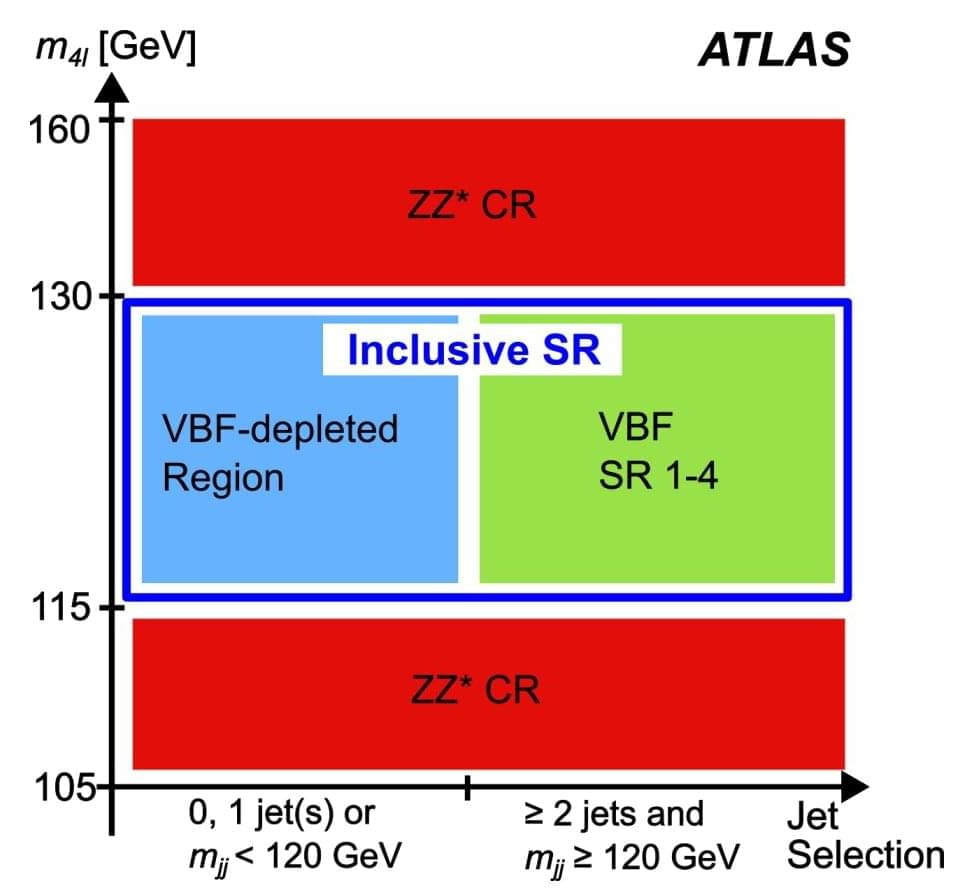

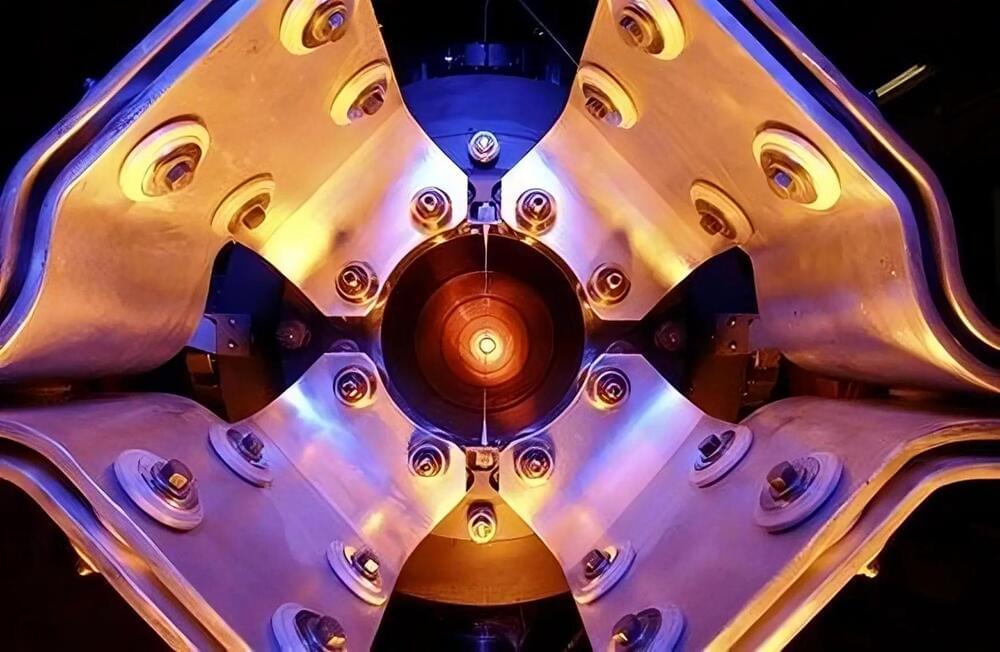

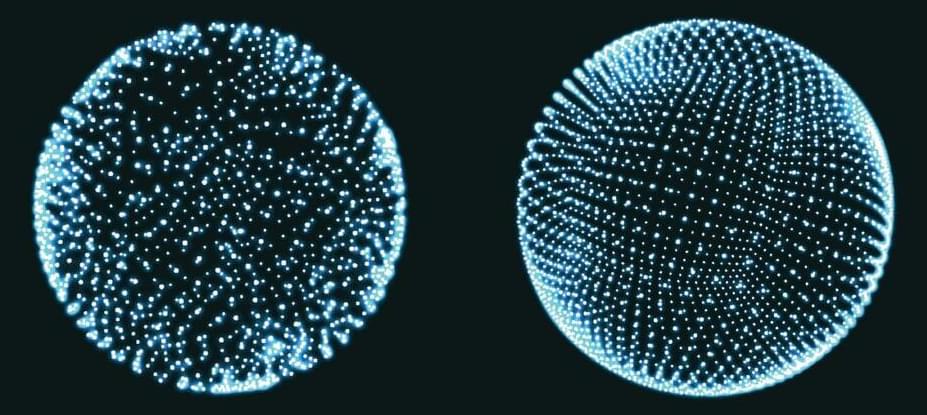

In a new analysis of its full dataset from Run 2 of the LHC, the ATLAS collaboration tested the Higgs-boson interactions with the carriers of the weak force, the W and Z bosons, looking for signs of CP violation. The collaboration studied Higgs-boson decays into two Z bosons, each of which transforms into a pair of leptons (an electron and a positron or a muon and an antimuon), thus resulting in four charged leptons. The researchers also studied interactions in which two W or Z bosons combine to produce a Higgs boson. In this case, one quark and one antiquark are produced together with the Higgs boson, creating ‘jets’ of particles in the ATLAS detector.