Scientists say they were able to stimulate hair growth in mice by utilizing an RNA particle, a development that could eventually lead to another treatment for baldness in humans.

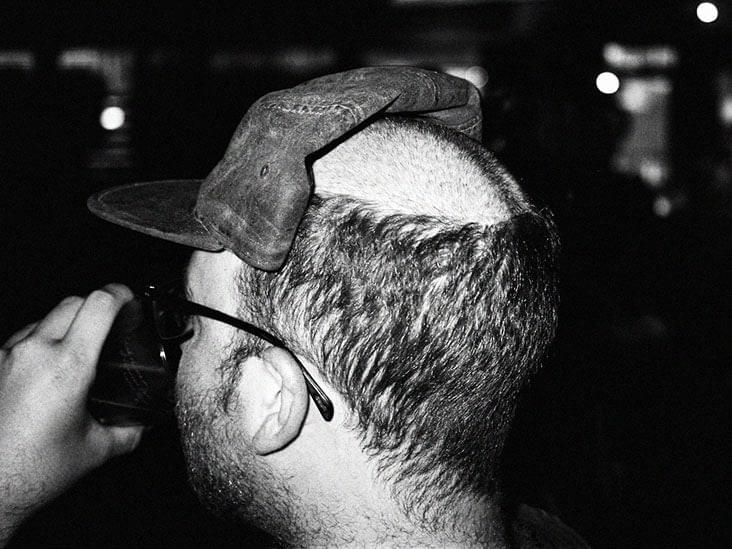

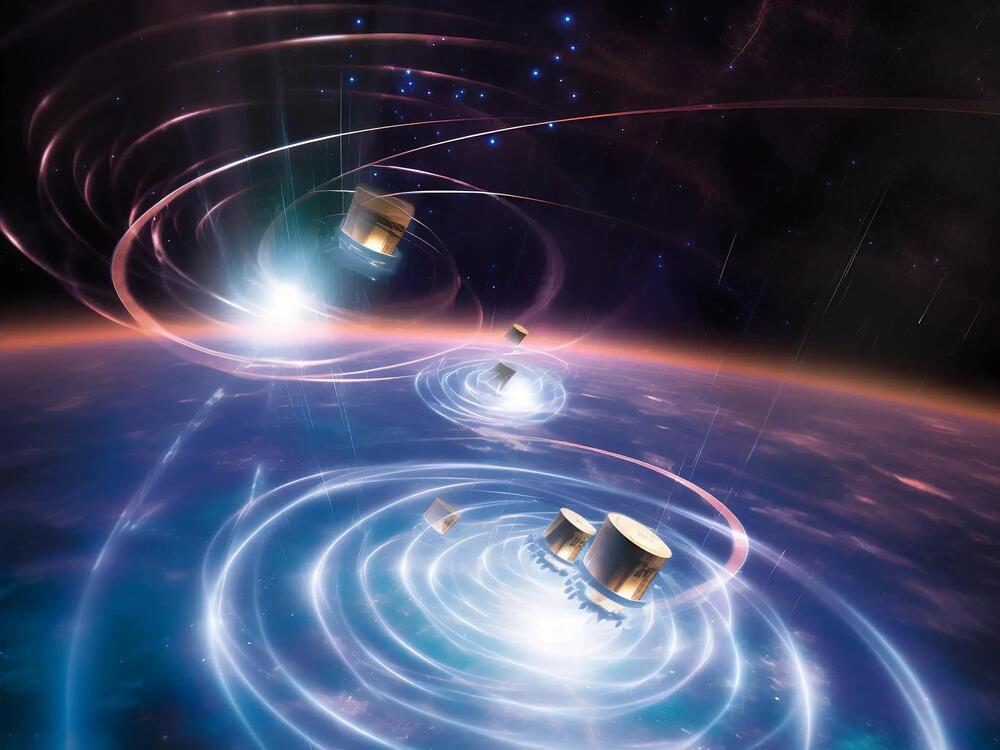

Superfast, subatomic-sized particles called muons have been used to wirelessly navigate underground for the first time. By using muon-detecting ground stations synchronized with an underground muon-detecting receiver, researchers at the University of Tokyo were able to calculate the receiver’s position in the basement of a six-story building.

As GPS cannot penetrate rock or water, this new technology could be used in future search and rescue efforts, to monitor undersea volcanoes, and guide autonomous vehicles underground and underwater. The findings are published in the journal iScience.

GPS, the global positioning system, is a well-established navigation tool and offers an extensive list of positive applications, from safer air travel to real-time location mapping. However, it has some limitations. GPS signals are weaker at higher latitudes and can be jammed or spoofed (where a counterfeit signal replaces an authentic one). Signals can also be reflected off surfaces like walls, interfered with by trees, and can’t pass through buildings, rock or water.

How can the mindless microscopic particles that compose our brains ‘experience’ the setting sun, the Mozart Requiem, and romantic love? How can sparks of brain electricity and flows of brain chemicals literally be these felt experiences or be ‘about’ things that have external meaning? How can consciousness be explained?

Free access to Closer To Truth’s library of 5,000 videos: http://bit.ly/376lkKN

Support the show with Closer To Truth merchandise: https://bit.ly/3P2ogje.

Watch more interviews on the mystery of consciousness: https://rb.gy/sxtbb.

Keith Ward is a British philosopher, theologian, pastor and scholar. He is a Fellow of the British Academy and (since 1972) an ordained priest of the Church of England. He was a canon of Christ Church, Oxford until 2003. Comparative theology and the relationship between science and religion are two of his main topics of interest.

Register for free at CTT.com for subscriber-only exclusives: https://bit.ly/3He94Ns.

A counterintuitive facet of the physics of photon interference has been uncovered by three researchers of Université libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. In an article published this month in Nature Photonics, they have proposed a thought experiment that utterly contradicts common knowledge on the so-called bunching property of photons. The observation of this anomalous bunching effect seems to be within reach of today’s photonic technologies and, if achieved, would strongly impact on our understanding of multiparticle quantum interferences.

One of the cornerstones of quantum physics is Niels Bohr’s complementarity principle, which, roughly speaking, states that objects may behave either like particles or like waves. These two mutually exclusive descriptions are well illustrated in the iconic double-slit experiment, where particles are impinging on a plate containing two slits. If the trajectory of each particle is not watched, one observes wave-like interference fringes when collecting the particles after going through the slits. But if the trajectories are watched, then the fringes disappear and everything happens as if we were dealing with particle-like balls in a classical world.

As coined by physicist Richard Feynman, the interference fringes originate from the absence of “which-path” information, so that the fringes must necessarily vanish as soon as the experiment allows us to learn that each particle has taken one or the other path through the left or right slit.

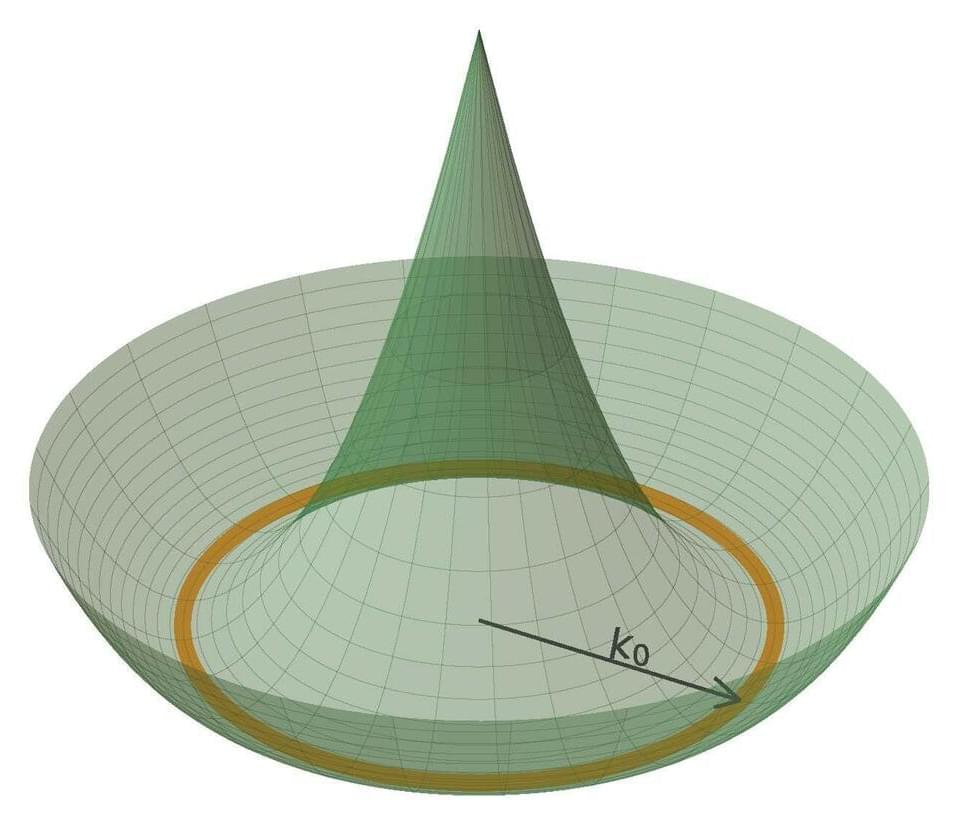

A team of physicists, including University of Massachusetts assistant professor Tigran Sedrakyan, recently announced in the journal Nature that they have discovered a new phase of matter. Called the “chiral Bose-liquid state,” the discovery opens a new path in the age-old effort to understand the nature of the physical world.

Under everyday conditions, matter can be a solid, liquid or gas. But once you venture beyond the everyday—into temperatures approaching absolute zero, things smaller than a fraction of an atom or which have extremely low states of energy—the world looks very different. “You find quantum states of matter way out on these fringes,” says Sedrakyan, “and they are much wilder than the three classical states we encounter in our everyday lives.”

Sedrakyan has spent years exploring these wild quantum states, and he is particularly interested in the possibility of what physicists call “band degeneracy,” “moat bands” or “kinetic frustration” in strongly interacting quantum matter.

A team of theoretical and experimental physicists has made a fundamental discovery of a new state of matter.

In our day-to-day life, we encounter three types of matter—solid, liquid, and gas. But, when we move beyond the realm of daily life, we see exotic or quantum states of matter, such as plasma, time crystals, and Bose-Einstein condensate.

These are observed when we go to low temperatures near absolute zero or on atomic and subatomic scales, where particles can have very low energies. Scientists are now claiming that they have found a new phase of matter.

Ultra-high pressure can have strange effects in physics and chemistry, and in a new study, high-pressure modeling has led to the prediction of four new compounds: compounds that don’t form in normal ways, have crystal structures we’ve never seen before, and can even act as superconductors in certain temperatures.

Those compounds are Li14 Cs, Li8Cs, Li7Cs, and Li6Cs, and they’re all formed from lithium (Li) and cesium (Cs) – though not in a conventional way. All four are superconductors, which means electricity can flow through them without resistance or energy loss.

The scientists behind the study used a special crystal structure prediction algorithm called USPEX (Universal Structure Predictor: Evolutionary Xtallography) to find these new compounds. It’s known as an evolutionary algorithm, using a range of methods to figure out the probability of how atoms will link together.

Over millennia, humans have observed and been inspired by beautiful displays of light bands dancing across dark night skies. Today, we call these lights the aurora: the aurora borealis in the northern hemisphere, and the aurora australis in the southern hemisphere.

Nowadays, we understand aurorae are caused by charged particles from Earth’s magnetosphere and the solar wind colliding with other particles in Earth’s upper atmosphere. Those collisions excite the atmospheric particles, which then release light as they “relax” back to their unexcited state.

The color of the light corresponds to the release of discrete chunks of energy by the atmospheric particles, and is also an indicator of how much energy was absorbed in the initial collision.

Researchers have reached a significant milestone in the field of quantum gravity research, finding preliminary statistical support for quantum gravity.

In a study published in Nature Astronomy on June 12, a team of researchers from the University of Naples “Federico II,” the University of Wroclaw, and the University of Bergen examined a quantum-gravity model of particle propagation in which the speed of ultrarelativistic particles decreases with rising energy. This effect is expected to be extremely small, proportional to the ratio between particle energy and the Planck scale, but when observing very distant astrophysical sources, it can accumulate to observable levels. The investigation used gamma-ray bursts observed by the Fermi telescope and ultra-high-energy neutrinos detected by the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, testing the hypothesis that some neutrinos and some gamma-ray bursts might have a common origin but are observed at different times as a result of the energy-dependent reduction in speed.