Year 2013 Basically they found out water is quantum which could then be turned into a water quantum computer.

Water is vital to life as we know it, but there is still a great deal unknown when it comes to correctly modeling its properties. Now researchers have discovered room-temperature water may be even more bizarre than once suspected — quantum physics suggest its hydrogen atoms can travel surprisingly farther than before thought, report findings detailed in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Water is just made of two hydrogen atoms and an oxygen atom, but despite its apparent simplicity, liquid water displays a remarkable number of unusual properties, such as how it decreases in density upon freezing, and the existence of some 19 different forms of ice. Scientists traditionally ascribe water’s peculiar behavior to the hydrogen bond. Water is polar — partial electric charges separate within the molecule, leading to slightly positively charged hydrogen ends and a negatively charged oxygen middle. As such, the hydrogens in one water molecule can get attracted to the oxygen in another, a hydrogen bond that can help explain why water has such a high boiling point, for example.

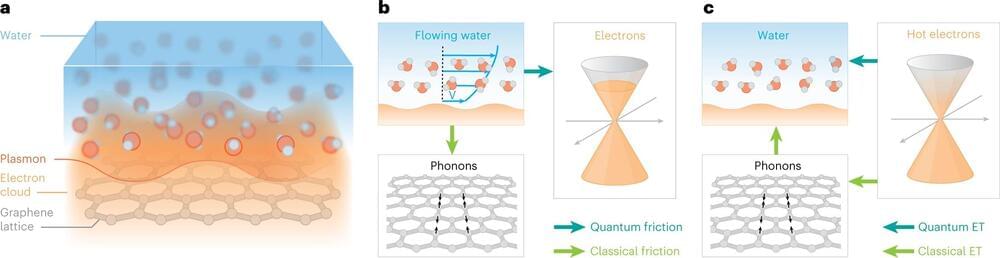

All of water’s anomalies, together with its unquestionably vital role in climate and life on Earth, have led to intense research around the globe, but still much remains unknown about it. To shed light on water’s behavior, materials scientist Michele Ceriotti at the University of Oxford in England and his colleagues modeled how the atomic nuclei of water’s hydrogen might behave in a quantum way — that is, not like points as the above explanation of hydrogen bonding from classical physics would suggest, but as more delocalized, cloud-like objects.