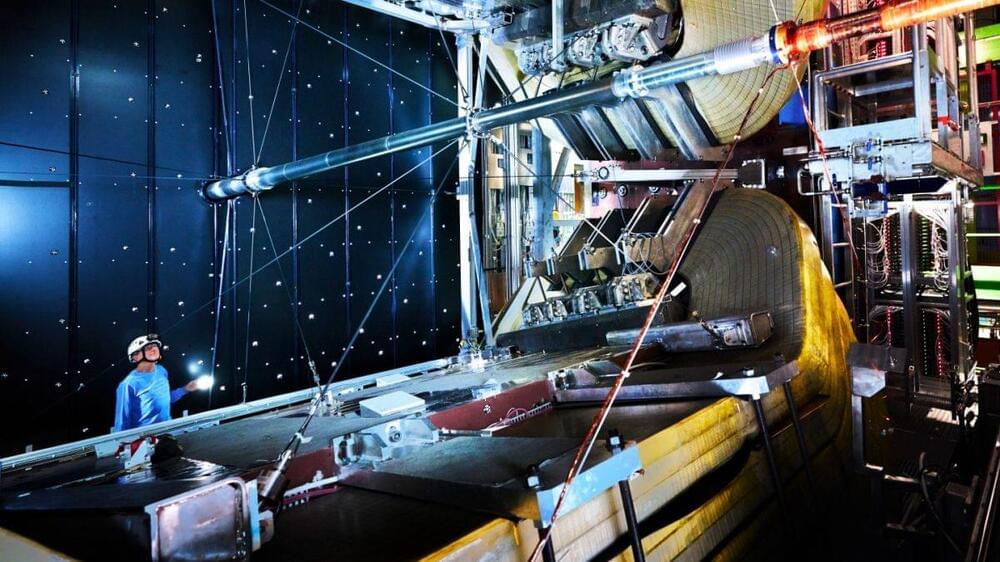

A team of physicists, including University of Massachusetts assistant professor Tigran Sedrakyan, recently announced in the journal Nature that they have discovered a new phase of matter. Called the “chiral bose-liquid state,” the discovery opens a new path in the age-old effort to understand the nature of the physical world.

Under everyday conditions, matter can be a solid, liquid, or gas. But once you venture beyond the everyday—into temperatures approaching absolute zero.

Absolute zero is the theoretical lowest temperature on the thermodynamic temperature scale. At this temperature, all atoms of an object are at rest and the object does not emit or absorb energy. The internationally agreed-upon value for this temperature is −273.15 °C (−459.67 °F; 0.00 K).