Peter Atkins, James Ladyman, and Joanna Kavenna argue over the existence of physical reality.

Watch the full debate at https://iai.tv/video/the-world-that-disappeared?utm_source=Y…escription.

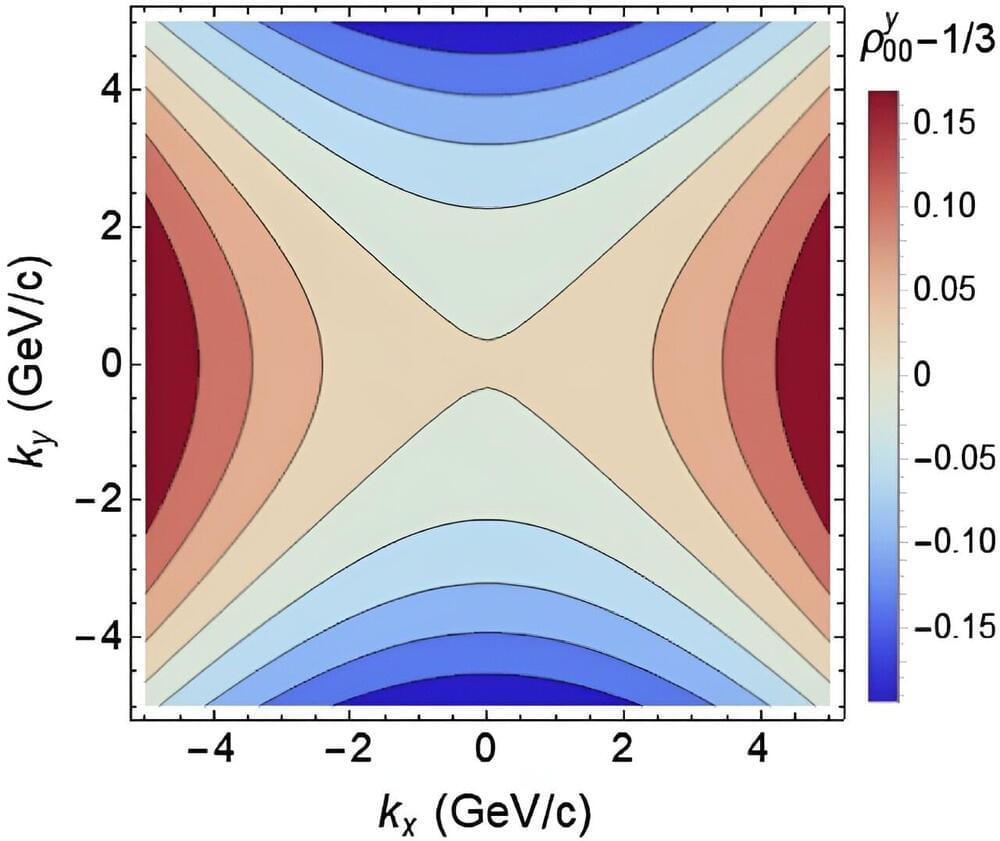

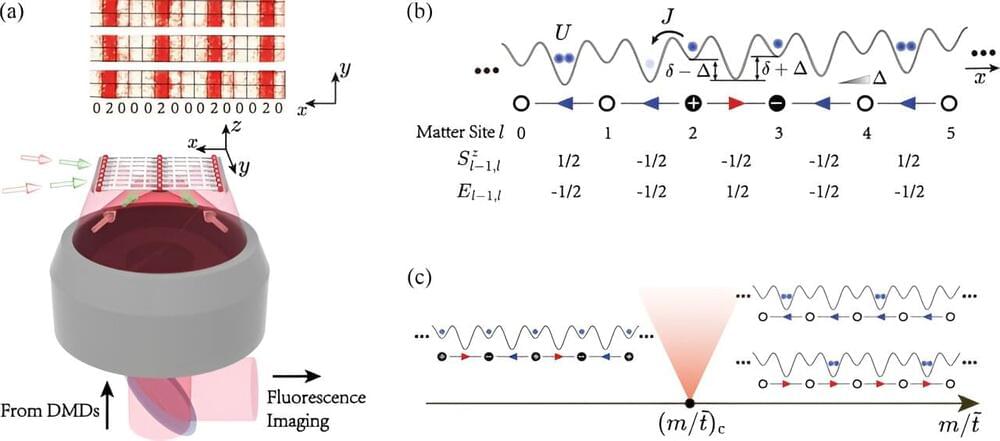

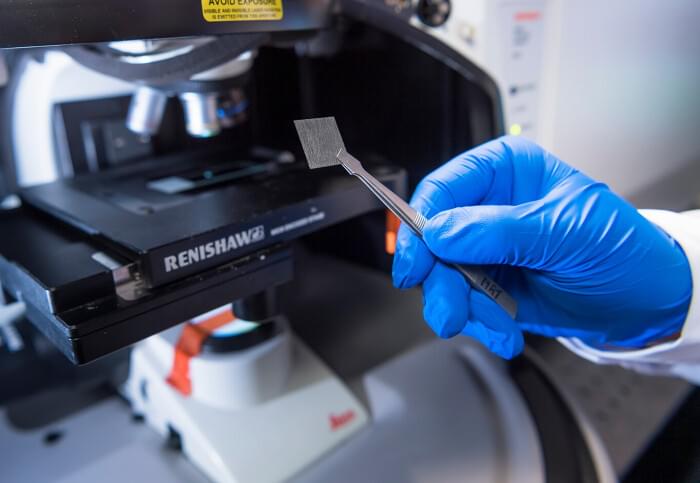

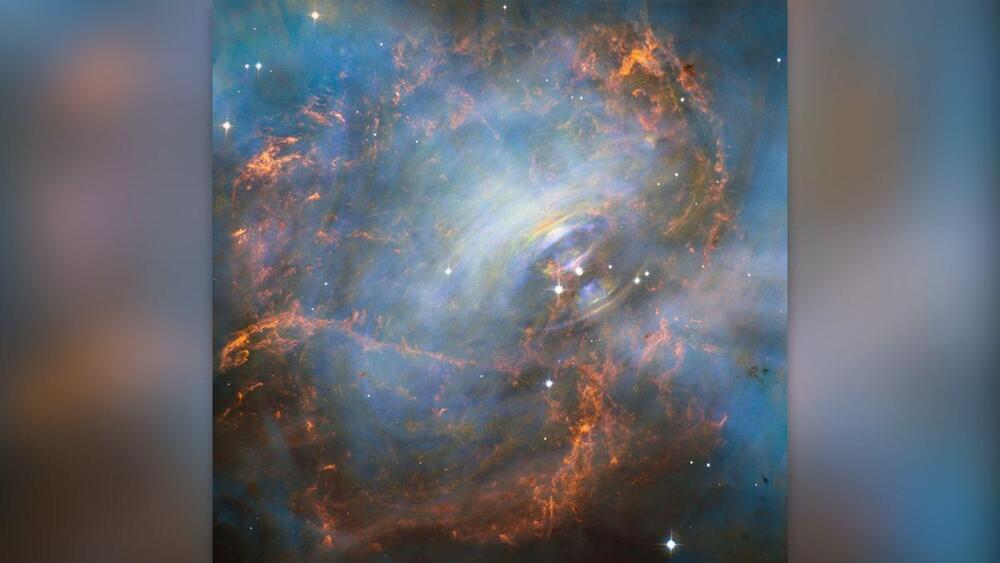

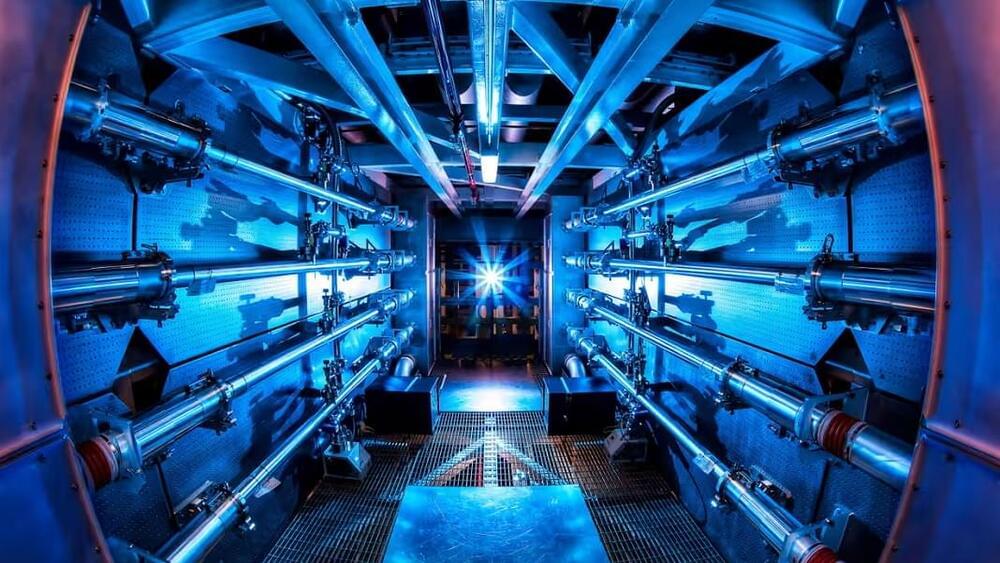

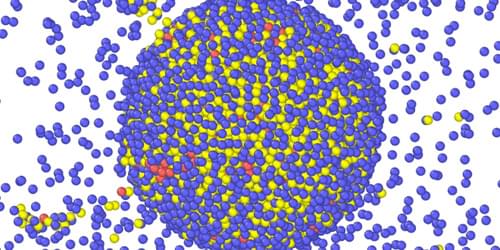

No-one who has ever stepped on a Lego brick could doubt the reality of physical objects. Yet from Heraclitus to George Berkeley, many philosophers claimed to have disproven the existence of things. Now even high-energy particle physicists are inclined to agree and describe material stuff as energy, or even as mathematical constructs. Could the world truly be made up of fields and processes, rather than physical stuff? Or is science trapped in a philosophical fantasy from which it needs to escape?

#PhysicalRealityDebate #MaterialistWorld.

#RelatingToReality.

Chemist and Fellow of Lincoln College Peter Atkins, Philosopher of Science at the University of Bristol James Ladyman and author of A Field Guide to Reality Joanna Kavenna debate whether the everyday objects that surround us are an illusion. Julian Baggini hosts.

To discover more talks, debates, interviews and academies with the world’s leading speakers visit https://iai.tv/subscribe?utm_source=YouTube&utm_medium=descr…sappeared.