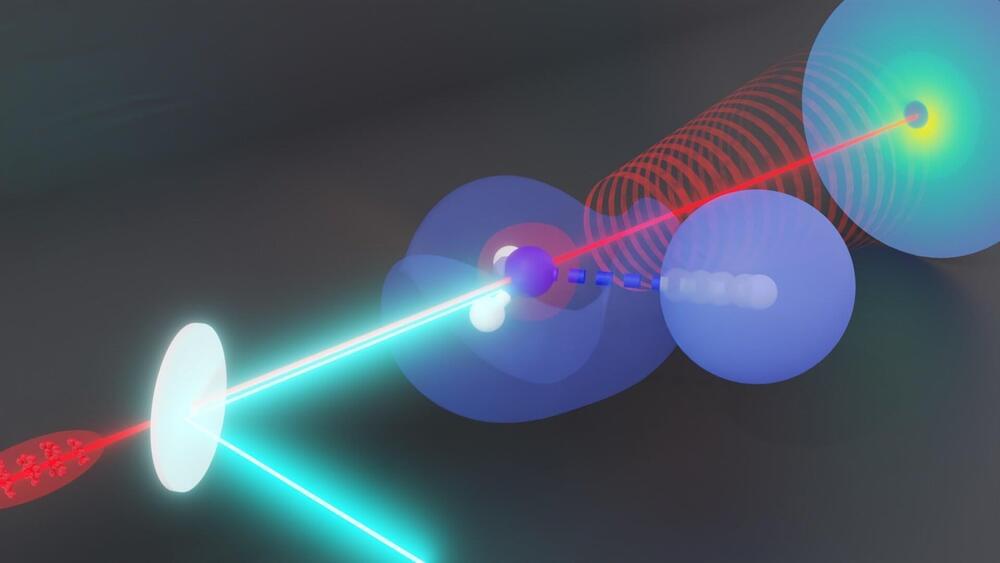

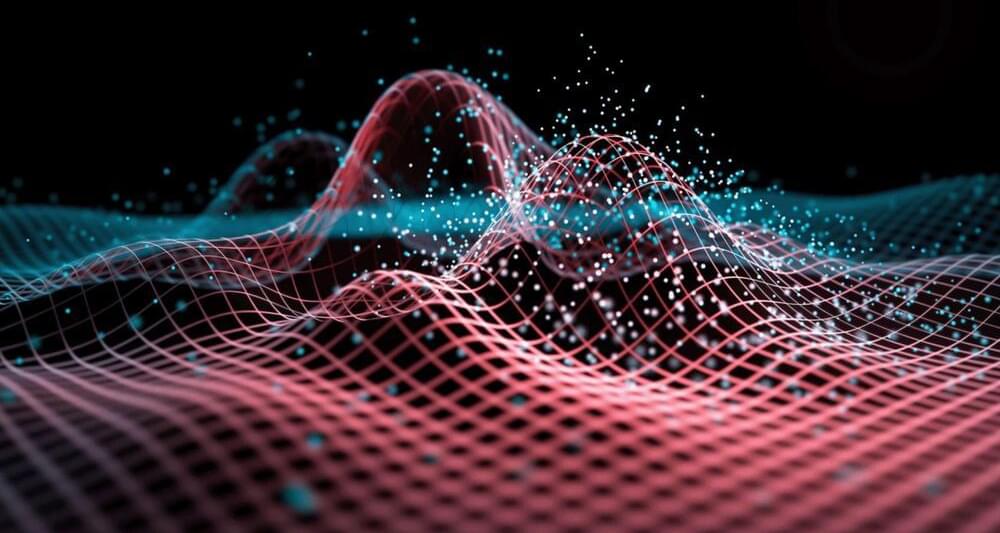

“Using the new quantum ruler to study how the circular orbits vary with magnetic field, we hope to reveal the subtle magnetic properties of these moiré quantum materials”

Graphene, a single-atom-thick sheet of carbon, is renowned for its exceptional electrical conductivity and mechanical strength.

However, when two or more layers of graphene are stacked with a slight misalignment, they become moiré quantum matter, opening the door to a world of exotic possibilities. Depending on the angle of twist, these materials can generate magnetic fields, become superconductors with zero electrical resistance, or transform into perfect insulators.