A mysterious, extremely energetic particle, known as the Amaterasu particle, was detected coming from a distant region of space, and scientists have proposed explanations for its origin, potentially tracing it back to a starburst galaxy like Messier 82 ##

## Questions to inspire discussion.

Understanding Ultra-High Energy Cosmic Rays.

🔬 Q: What makes the Amaterasu particle exceptionally powerful? A: The Amaterasu particle detected in Utah in 2021 carries energy 40 million times higher than anything produced on Earth, equivalent to a baseball traveling at 100 km/h compressed into a single subatomic particle, making it one of the most energetic particles ever detected.

Solving the Origin Mystery.

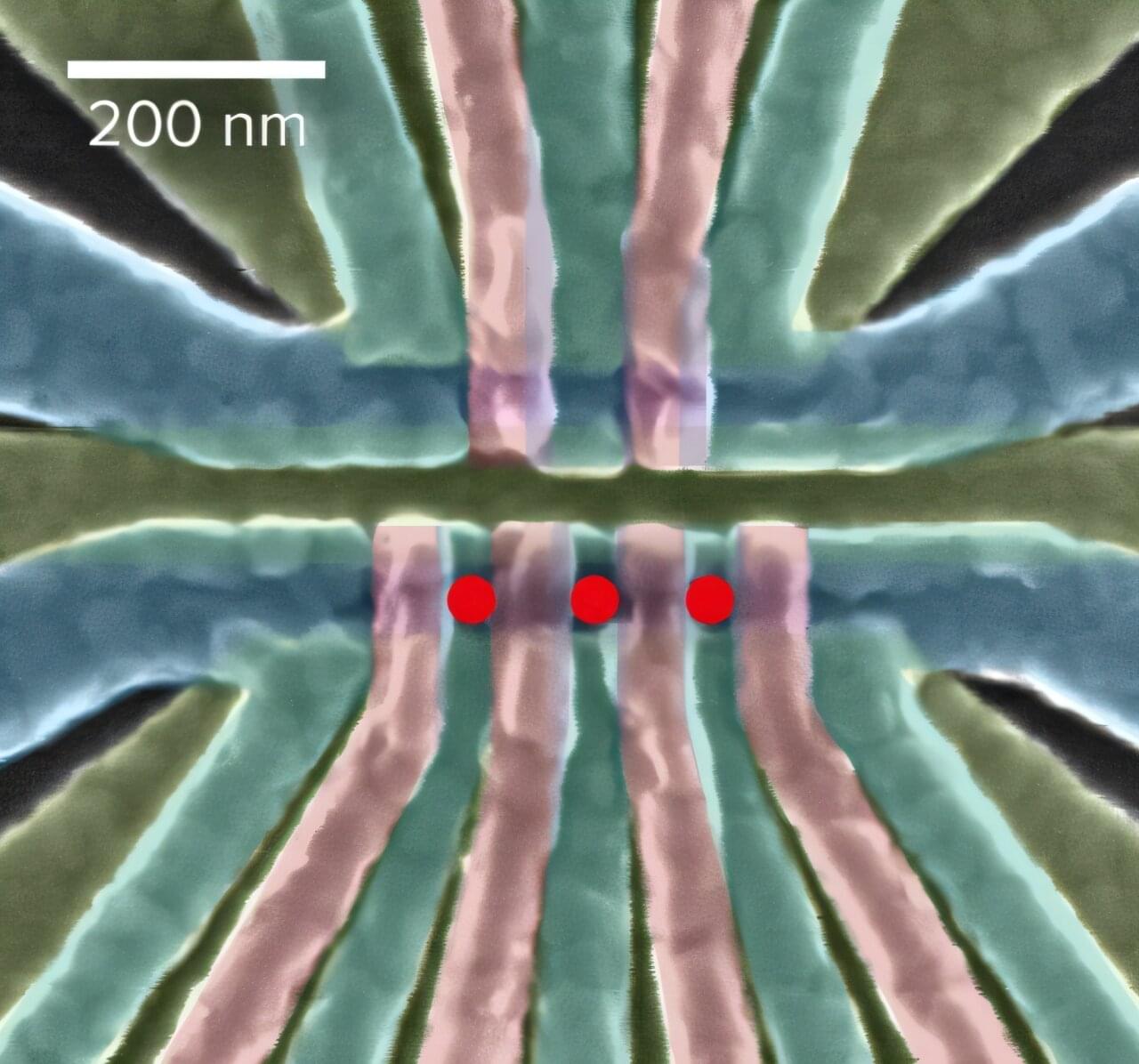

🎯 Q: Where did scientists determine the Amaterasu particle actually originated? A: A 2026 study by Max Planck Institute scientists using approximate Bayesian computation and 3D magnetic field simulations traced the particle’s origin to a starburst galaxy like Messier 82, located 12 million light-years away, rather than the initially suspected local void with only six known galaxies.