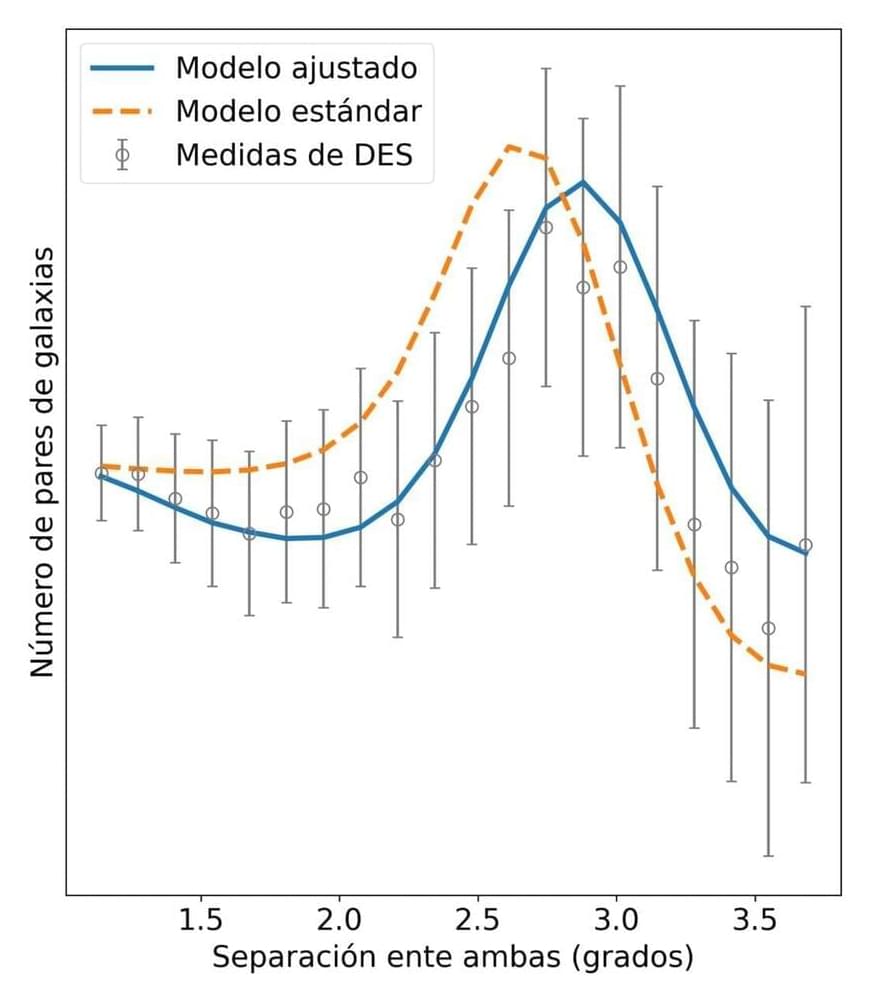

Gravitationally speaking, the universe is a noisy place. A hodgepodge of gravitational waves from unknown sources streams unpredictably around space, including possibly from the early universe.

Scientists have been looking for signs of these early cosmological gravitational waves, and a team of physicists have now shown that such waves should have a distinct signature due to the behavior of quarks and gluons as the universe cools. Such a finding would have a decisive impact on which models best describe the universe almost immediately after the Big Bang. The study is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Scientists first found direct evidence for gravitational waves in 2015 at the LIGO gravitational wave interferometers in the US. These are singular (albeit tiny amplitude) waves from a particular source, such as the merger of two black holes, which wash past Earth. Such waves cause the 4-km perpendicular arms of the interferometers to change length by miniscule (but different) amounts, the difference detected by changes in the resulting interference pattern as laser beams travel back and forth in the detector’s arms.